Editors Note: Weelunk, as a subsidiary of Wheeling Heritage, is committed to telling diverse, nuanced, and difficult histories, especially when those narratives occur in our own backyard. The line between cultural appreciation and appropriation has long been a challenge, and it is a societal infrastructure from which no person or group is exempt. As a community that lives on Indigenous lands and uses Indigenous words like “Wheeling” and “Weelunk,” it is our responsibility to acknowledge current and past appropriation to prevent it in the future and so Wheeling, as a community, may grow together.

What is the first thing that comes to mind when you stumble across the “Improved Order of Red Men” in old Wheeling records or newspapers?

An outdated Western film complete with gun slinging cowboys and grossly stereotyped Native Americans? Or perhaps something more Wheeling-centric—the misrepresented Mingo statue up on Wheeling Hill?

Well—the Improved Order of Red Men is a secret fraternal organization with a complicated history and appropriation of indigenous culture…and it had several chapters in Wheeling.

Origins of the Organization

Fraternal organizations, like the Freemasons or the Odd Fellows, have a long history in the US, becoming popular (and controversial) in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Each organization had its own attractions, but most offered a sense of companionship, shared values, and mutual benefit. Some have a service-oriented mission, while others focus more on providing opportunities for social interactions or upholding some other value or cause.

While the Improved Order of Red Men (IORM) was officially founded in 1833, the organization claims descendence from a chain of other secret fraternal organizations, including the Sons of Liberty, Sons of St. Tamina, and the Saint Tamina Society. The Society of Red Men was created out of the remains of these organizations in 1813 but was reorganized in Baltimore in 1833 to form the Improved Order of Red Men.1

What makes IORM unique from other fraternal organizations is its use of Native American or indigenous stereotypes, language, and culture. According to one of IORM’s librarians at its national library in Waco, Texas, “all fraternal organizations had a “hook” to get members in their early days. IORM used the Native motif.”2 These “motifs” include giving every member an “Indian name,” performing indigenous ceremonies and rituals, and even the name of the organization itself—“Red Men.” These practices go back to the Boston Tea Party in 1773 when some of the Sons of Liberty were supposedly disguised as indigenous peoples to protest the Tea Act by throwing the British East India Company tea into the Boston Harbor.3

IORM’s original precepts were “Freedom, Friendship, and Charity” and it was a semi-secret fraternal society that mostly operated in the mid-Atlantic and upper South regions of the US.4 The organization was very popular with German immigrants and German-Americans as it allowed them an avenue in the 19th and early 20th centuries to assimilate into American society.5 It continues to exist today, however, its membership is a small fraction of what it boasted at the height of its popularity.

Origins of IORM in Wheeling

During the mid-to-late 19th century, Wheeling had a quickly growing German immigrant population and was therefore primed for an eager group of IORM members. The first IORM chapter or “tribe” in Wheeling, Logan Tribe No. 21, was incorporated in 1853—ten years before West Virginia even became an independent state. It quickly became the largest IORM chapter in Virginia, boasting 120 members in 1859. When West Virginia formed in 1863, it was renamed Logan Tribe No. 1. For a while, they met at Crangle’s Block in Downtown Wheeling—across the street from where the WesBanco Headquarters are today, before moving to the corner of 23rd and Market Street, next to Centre Market, in 1887.6 Records even show that Wheeling’s chapter meetings were conducted in German.7

Other than the Logan Tribe, there were two other documented IORM chapters in Wheeling’s history. Cornstalk Tribe No. 2 was incorporated in 1868, but there is very little known about its history.8 The final Wheeling IORM chapter, The Grey Eagle Tribe No. 5, started in 1883 and met at 3521 Jacob Street in South Wheeling. They were all defunct by 1921.9

While most fraternal organizations have historically been exclusively for men, that did not stop women from being involved. The Degree of Pocahontas was created as a sister branch of the IORM, complete with similar practices and governance structures. In Wheeling, the Kolgglitskilg Council No. 1 was instituted in 1887, and like the IORM chapters in Wheeling, it was mostly made up of German-speaking women. A few years later, it was reorganized as the Ohio Valley Council No. 1 in 1889.10 The first “Great Prophetess” of the entire Great Council of West Virginia Degree of Pocahontas was a woman from Wheeling, Elizabeth Hydinger.11

While IORM provided an opportunity for immigrants and their families to become “American,” it also acted as a mutual aid society. Members paid dues and the organization made sure that they and their families were taken care of in times of need. For example, in the mid-1860s, the Logan Tribe established a cemetery in the hills above Center Wheeling for members and their families, ensuring they would be accounted for, even in death.12

Although there are no longer active IORM chapters in Wheeling, the organization still exists in other towns and cities, even as close as Martins Ferry, right across the river. There is no doubt that the local IORM chapters once provided an important sense of belonging, a social structure, and a place to speak their first language outside of the home. However, it was at the cost of perpetuating harmful stereotypes and claiming aspects of cultures that were not theirs.

What is Cultural Appropriation?

There is a difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation, but sometimes the fine line between the two can be unclear. Cultural appreciation is someone “seeking to understand and learn about another culture in an effort to broaden their perspective and connect with others cross-culturally.” Cultural appropriation is the adoption or taking of aspects of one culture by people who are not part of that culture, generally for one’s own benefit.13 These could include ideas, attire, practices/traditions, symbols, behavior, etc. Even if not done intentionally, many of these acts of cultural appropriation are harmful and/or offensive and often encourage and perpetuate harmful stereotypes of the other culture.

The vast majority of IORM members were not indigenous or of indigenous descent. Therefore, the use of indigenous cultural elements without the proper context and respect is problematic. In addition, there is a long history of indigenous peoples being prevented from speaking their languages, practicing their traditions, and having their cultures erased in order to force assimilation. To have non-indigenous people take and repurpose their cultural elements and traditions without repercussion adds further injury and pain.

IORM became very popular during the era of Westward Expansion, when many Anglo-Americans believed that it was the United States’ “manifest destiny” and right to take over land throughout North America, removing or killing upwards of tens of thousands of indigenous peoples. IORM histories from the early 20th century claim that through the organization’s practices, “the memory of the Primitive Red Men will be preserved to the latest period of recorded time”…as if indigenous peoples were extinct.14 Yet, at the same time, indigenous peoples’ cultures and ways of life were being oppressed and their land stolen.

The indigenous peoples of America consist of many different tribes and groups of people with their own distinct histories, cultures, traditions, and languages. However, the descriptions and practices of IORM lump them all together and treat them as one homogenous group of “red men,” a term largely considered offensive and derogatory today. Additionally, the IORM caricatures and references to the “primitive” further entrench the harmful racist stereotypes of indigenous peoples as undeveloped or uncivilized.

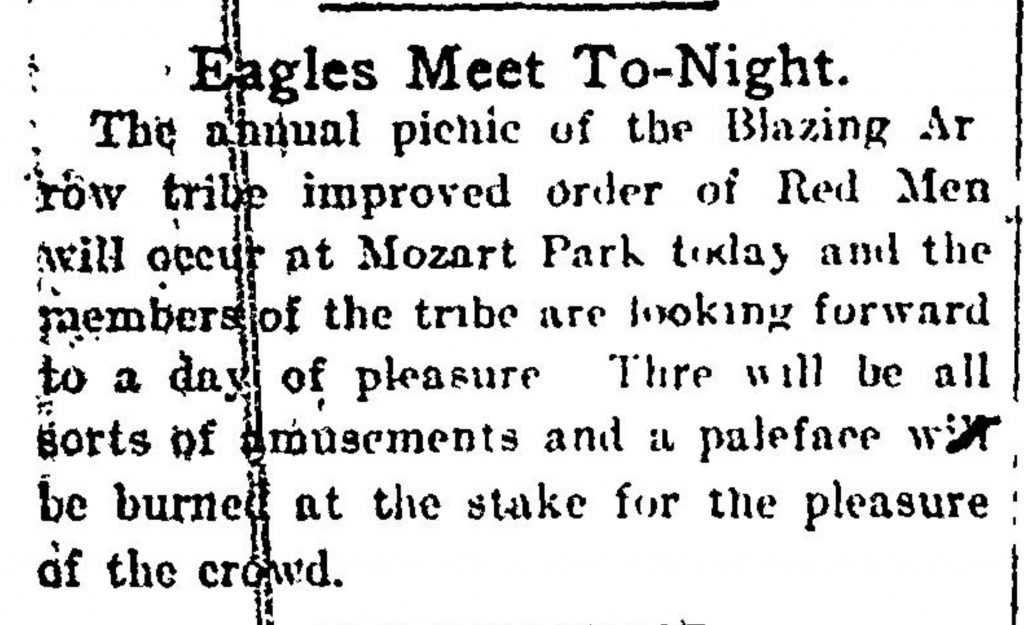

On a local level, the Wheeling IORM chapters would occasionally hold events with chapters from other towns, such as Benwood, and invite the public to attend. These events would capitalize on sacred indigenous traditions and perform stereotyped versions for the public’s entertainment and profit. For example, in 1903, the Wheeling Intelligencer advertised the annual IORM picnic in Mozart Park where there was to be “all sorts of amusements and a paleface will be burned at the stake for the pleasure of the crowd.”15 Obviously, no one was actually burned at the stake, but the play acting perpetuated the racist stereotype of the “savage Indian.”

IORM and Combating Cultural Appropriation Today

Combating cultural appropriation is a continuing battle, but recent years have seen limited positive change, such as the renaming/rebranding of certain sports teams that use indigenous stereotypes. However, when a librarian at the National Red Men Museum and Library was asked about the continued name of the organization, largely considered offensive today, he responded saying that “I cannot speak for the organization, but they usually do not respond to criticism of the name.”16

While we cannot change or take back the harm that the cultural appropriation of the past has created, everyone has a responsibility to learn about its history and ensure that it does not continue into the future. Historically, Thanksgiving has been a holiday where harmful indigenous stereotypes are amplified. Practices like school children dressing up like “pilgrims and Indians,” while sadly commonplace, are examples of how blatant cultural appropriation has bled into schools. If you celebrate the holiday, take some time to consider the ways in which non-indigenous people have taken or used indigenous language, culture, and ways of life for their own benefit.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 George W. Lindsay, Charles C. Conley, and Charles H. Litchman, Official History of Improved Order of Red Men: Compiled Under Authority From the Great Council of the United States by Past Great Incohonees, (Boston: The Fraternity Publishing Company, 1893), accessed November 22, 2020, https://archive.org/stream/officialhistoryo00lindiala/officialhistoryo00lindiala_djvu.txt

2 David Lintz, email message to Emma Wiley, November 6, 2020.

3 Lindsay, Conley, and Litchman, Official History of Improved Order of Red Men.

4 Dale T. Knobel, “To Be an American: Ethnicity, Fraternity, and the Improved Order of Red Men,” Journal of American Ethnic History 4, no. 1 (1984): 79-80, accessed November 20, 2020, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27500352.

5 Knobel, 64-65.

6 David Lintz, email message to Emma Wiley, November 6, 2020.

7 David Lintz, email message to Emma Wiley, November 6, 2020.

8 Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, Feb 7, 1868, p. 2.

9 David Lintz, email message to Emma Wiley, November 6, 2020.

10 Kenneth R. Reffeitt, Centennial History of The Great Council of West Virginia: Degree of Pocahontas of The Improved Order of Red Men, 1902-2002, (Huntington, WV: The Great Council of West Virginia, Improved Order of Red Men, 2007), 4.

11 Reffeitt, 5.

12 Daily Intelligencer, February 3, 1864, p. 2.; “Our Silent Cities: A History of the Cemeteries in and Around Wheeling, Which will be of Interest to Many of Our Readers,” The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, December 8, 1880.

13 Kelsey Holmes, “Cultural Appreciation vs. Cultural Appropriation: Why It Matters,” Greenheart International, accessed November 24, 2020, https://greenheart.org/blog/greenheart-international/cultural-appreciation-vs-cultural-appropriation-why-it-matters/#:~:text=Appreciation%20is%20when%20someone%20seeks,for%20your%20own%20personal%20interest

14 Lindsay, Conley, and Litchman, Official History of Improved Order of Red Men.

15 “Eagles Meet To-Night,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 2, 1903, p. 3.

16 David Lintz, email message to Emma Wiley, November 6, 2020.