Kibbeh. Pierogi. Schnitzel. Marinara. They’re all still here. Sometimes in restaurants and at festivals, but, more often, hunkered down in family homes, churches and community groups.

On Saturday, Sept. 28, however, area foodies will have an insider’s chance to literally taste their way through Wheeling’s diverse history. From 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. that Saturday, Wheeling Heritage is hosting an inaugural Cultural Food Tour that will include German, Lebanese, Polish and Ukrainian cuisine.

On Saturday, Sept. 28, however, area foodies will have an insider’s chance to literally taste their way through Wheeling’s diverse history. From 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. that Saturday, Wheeling Heritage is hosting an inaugural Cultural Food Tour that will include German, Lebanese, Polish and Ukrainian cuisine.

“It’s really been interesting to me that so many places are still doing this (food production),” said Betsy Sweeny, a Wheeling Heritage spokesperson. That organization, which owns Weelunk, is charged by the National Park Service to preserve city history while helping to maintain a livable, workable community.

A former resident of Pittsburgh and Virginia, Sweeny said many larger cities have combined ethnic communities — such as a single church community that would represent all of Eastern Europe.

“We have all of these places still separate and cooking distinctly,” Sweeny added. “That’s really special.”

160 YEARS OF KIBBEH

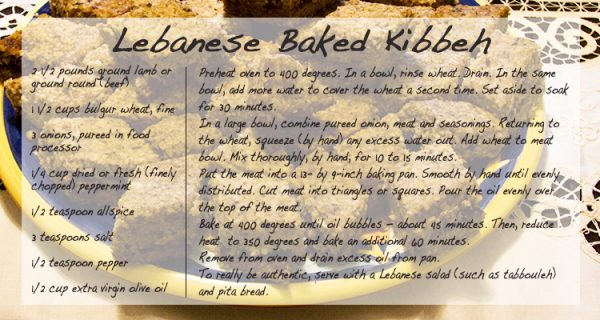

Kibbeh, a ground-meat dish that is classically paired with hummus and tabbouleh in Lebanon, will be among the culturally distinct foods offered on the tour.

It’s a dish that has a long history in Wheeling.

Religious persecution drove the first wave of Lebanese families here. It was the 1860s, and a handful of immigrants came to work in the coal mines. They lived and house-churched in what is now the Centre Market Historic District, according to Monsignor Bakhos Chidiac.

Chidiac, a history buff who prefers to go by the name “Father Bob,” said it was the second, much larger wave of immigration in the early 1900s (caused by famine), that really made for a vibrant Lebanese community, though.

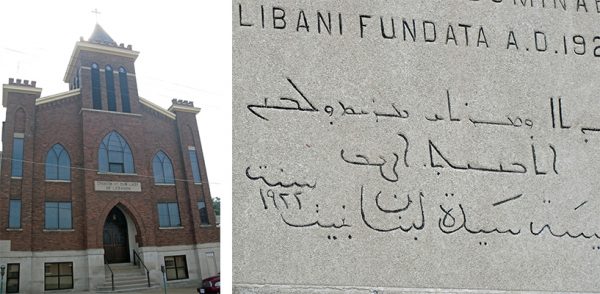

At its peak, more than 1,000 Lebanese families called Wheeling home. And by 1922, that community built Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church at 2216 Eoff St. It is the only Maronite congregation in the state and one of only about 100 nationwide, he said.

“From (the Christian massacre in) 1860 to the 1900s was only 40 years, a short time,” Chidiac said of the second wave. “The Christians did not feel safe, and famine seemed like the last straw. They left.”

Chidiac, who himself left Lebanon for America in 1994 and has a master’s degree in history, has tracked the immigration phenomenon.

“The first wave of immigrants gathered around a church,” he said of the difficulty of relocating on the other side of the world. “All the people are there. They speak the same language. They help each other find jobs.”

Then, as an American-born generation matured, they, in turn, migrated, he said. This time, they moved to elsewhere in America — following everything from marriages to non-Lebanese spouses to job opportunities to adventure.

While the church has about 200 attendees today, Chidiac said many of the descendents still return to Wheeling for the Mahrajan, an annual festival that has celebrated Lebanese food, music and dance each August at Oglebay Park since 1933.

“The hub was here,” Chidiac said. “They spread all over and, now, they come back.”

TASTE OF HOME

The lure of food is something that resounds with Our Lady member Linda Fadoul-Duffy. Her family has not only been cooking Lebanese food in Wheeling homes since the early 1900s, they’ve been sharing it with the masses.

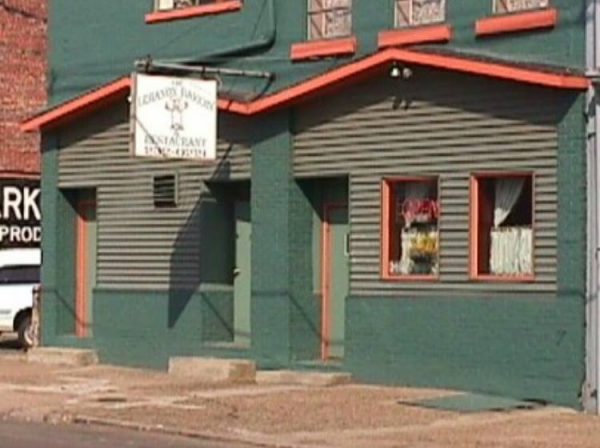

Fadoul-Duffy’s late mother, Rose Shedeed-Fadoul, co-founded the Lebanon Bakery and restaurant in 1955. It was family operated until closing in 2016.

“I think everyone in the family worked in the restaurant at some point,” Fadoul-Duffy said. “(Plus,) growing up with six children in the family, you learned to cook for a crowd.”

Fadoul-Duffy is preparing food for the Our Lady part of the tour with co-coordinator Mary Zaid-Frees. Kibbeh, pita and, likely, some sort of sauce will be on the menu there. The church will also have additional Lebanese foods for sale separate from the tour, she said.

“I think it’s great that the community can learn from all the nationalities in our city,” Fadoul-Duffy said of sharing her kibbeh recipe in addition to preparing tour food. “But, giving the recipe doesn’t mean you can make it exactly the same way. You have to know how to work it.”

To that end, her recipe addresses a common problem — insufficient mixing of the seasonings and the meat. “It’s not like a meatloaf,” she cautioned, recommending home cooks spend 10-15 minutes working the mix with their hands.

“All those little things,” Duffy said of what’s usually not in a recipe. “There are some things even your parents don’t tell you. They might say a ‘pinch,’ but don’t tell you it’s more like three pinches.”

Fadoul-Duffy, who married a man of Scottish, Irish and German heritage, said she doesn’t really cook that much Lebanese food at home. But, when she does, kibbeh is a favorite.

Chidiac chimed back in at this point, expressing an interest in many kinds of food.

“We are not one way,” the priest said of Americans. “We are living in a melting pot.”

He hopes tour guests will enjoy their taste of Lebanon, however, joking that, in that culture, hosts expect guests to, “eat as much as you love us.”

And, he hopes Wheeling will be loving Lebanese food for a long time. “If there is one person left in Wheeling of Lebanese origin, he should keep the tradition going,” Chidiac said.

DIP INTO THE MELTING POT

Tickets for the Wheeling Heritage Cultural Food Tour can be reserved online at WheelingHeritage.org. They are $20 each, with children under 10 eating free. There are a limited number of tickets. Reservation is recommended, but remaining tickets can be purchased at the check-in site, South Wheeling Preservation Alliance at 3501 Jacob St.

After checking in to get their passport-style ticket and a map, participants have from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. to complete the self-guided tour in any order they desire. At the event’s end, tickets can be returned to the check-in site for a raffle. Dessert will also be offered at that site.

Each site will offer a small plate of food that represents its ethnic heritage and a card that will include a recipe and some cultural background.

Participating sites include:

• Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church; Lebanese food; 2216 Eoff St.

• Our Lady of Perpetual Help; Ukrainian food; 4136 Jacob St.

• Polish-American Patriot Club, Polish food; 4410 Jacob St.

• St. Paul’s Evangelical Church; German food, 3741 Wood St.

• A long-time journalist, Nora Edinger also blogs at noraedinger.com and Facebook and writes books. Her Christian chick lit and faith-related non-fiction are available on Amazon. She lives in Wheeling, where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household.