Wheeling’s long association with the steel and coal industries is one of the defining parts of its storied history. The reasons for their early success can easily be attributed to its exceptional location along the Ohio River. Early on, low-grade ore was readily available. However, factory expansions and growth in the Wheeling area resulted in other coal and ore sources being shipped to the Friendly City by steam towboats.

This age of industrial expansion that Wheeling came to enjoy also calls to mind many names associated with America’s industrial might during the same period; Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Mellon, and Morgan. These were America’s original and larger-than-life celebrity industrialists whose vast empires boasted more wealth than our present multi-billionaires could ever dream of having. Today, the very industries they started continue on in some form or another.

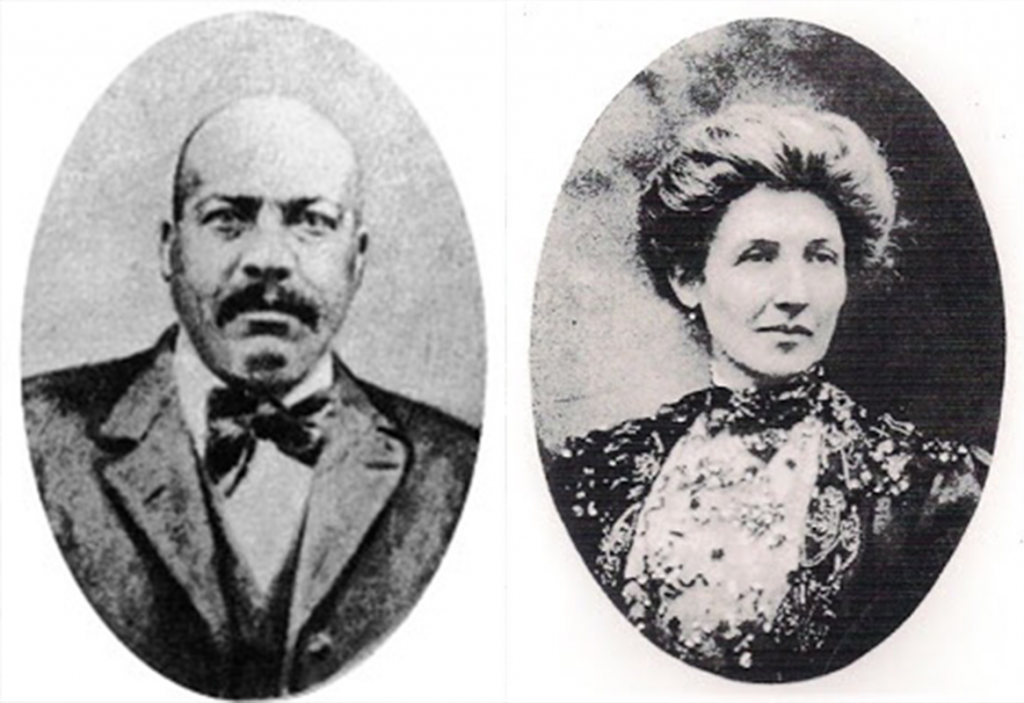

While their names are recognizable to many Americans, there is one little-known industrialist whose legacy has all but faded from the public’s mind but one whose role played a part in Wheeling’s own story. “Commodore” Cumberland W. Posey, Sr.’s incredible rise to prominence as an African American in an industry dominated by white men is a story unlike any of his contemporaries of the period. By the time he died in 1925, Posey had built a massive river and business empire around Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and beyond.

Challenging Beginnings

Upon the birth of their child Cumberland on August 30, 1858, former slaves Elizabeth and Alexander Posey could hardly have imagined the extraordinary life and fortune their son would someday make for himself. Even though they themselves were then free living in Port Tobacco, Maryland, slavery was still legal in many states at the time of his birth. It would not be until Cumberland was almost seven years old before slavery’s abolition was official.

While formerly enslaved people, Black Americans, and the Union collectively celebrated the end of slavery, young Posey’s and his father’s undoubted jubilation was overshadowed by the untimely death of his mother. However, it was that very loss that gave Posey his start when his father, an ordained minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, moved them to Winchester, Virginia in 1867 then to Belpre, Ohio in 1869.

The move to Ohio opened Posey’s eyes to the valuable necessity of river commerce. In his teens he secured his first job as a deck sweeper on an Ohio River ferry between Belpre, and Parkersburg, WV. Later he worked on the steamer Magnolia. The finely tuned machinery and steam engine of the boat immediately fascinated the young but brilliant teenager. It was during that time that Posey became determined to secure an engineer’s license.

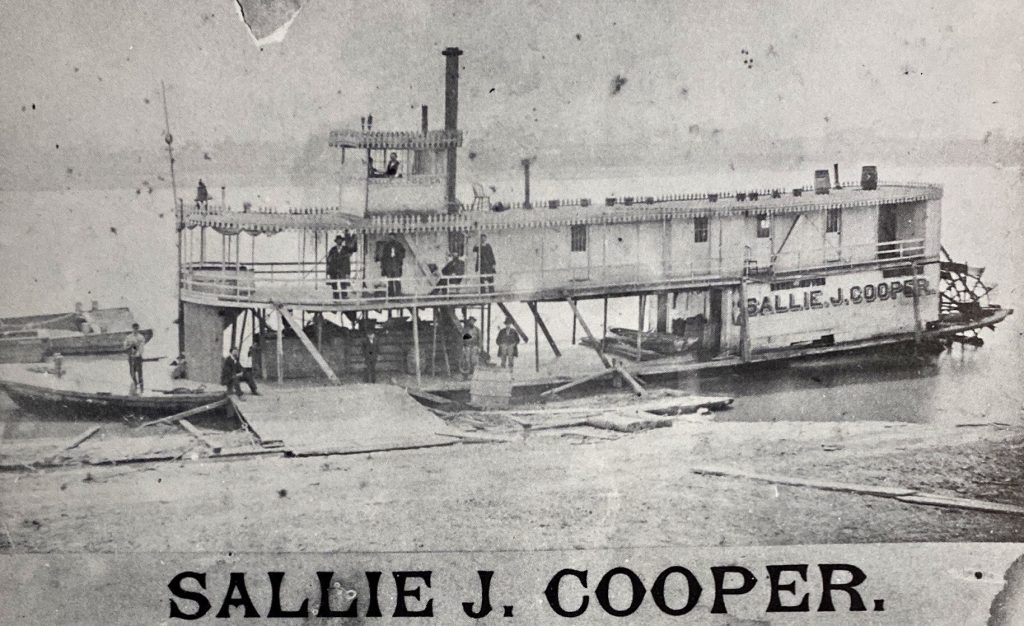

With encouragement and support from his boss and the owner of the Magnolia, Posey reportedly landed a job as a stoker aboard the steamer Sallie J. Cooper. Once in this position, he gained incredible skill and knowledge in understanding the intricate workings of steam engines resulting in his elevation to stroke engineer. Capitalizing on his continuing advancement, Posey took a job aboard the steamer Dick Henderson where he was made engineer. However, engineer was not the same as a licensed second engineer. Being a licensed second engineer meant he tested for and earned his title and rank.

Full Steam Ahead

Possessing the skills and experience to apply for a government license was one matter. Being Black and applying for such a license was entirely another. While many Black men during the period were relegated to being roustabouts, stewards, or cooks, Posey was about to break through that barrier. For him, it was simply one more rung on the ladder that he was determined to climb. Without hesitation, he applied for and, despite obstacles and opposition based solely on his race, obtained his license as a second engineer in 1877.

For about 14 years Cumberland continued working with Pittsburgh-based steamboat builder and owner Seward Hayes where he rose through the ranks. By 1890, he and his wife Anna had moved to Homestead, PA southeast of Pittsburgh. Posey officially earned his chief engineer’s license in 1892, further earning respect among his peers who then referred to him as “Captain” or “Cap” Posey. In doing so, he became the first African American in U.S. history to earn a chief engineer’s license.

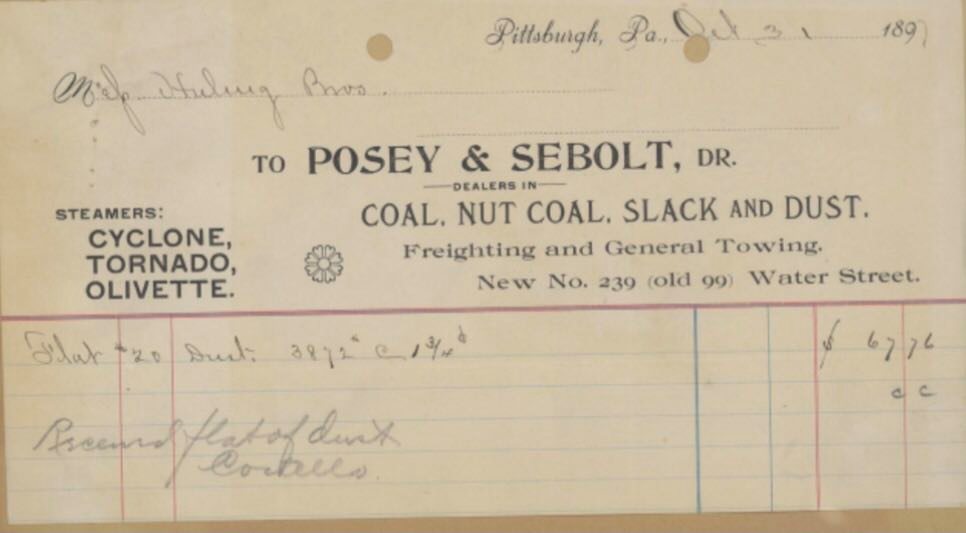

With license in hand, Posey immediately set out to build his own fleet of steamboats and soon founded the Posey Steamboat Company. Using his vast knowledge of the river and its commercial operations, he constructed vessels and barges specifically for transporting coal, ore, and other goods on the Ohio, Allegheny, and Monongahela Rivers. But his ambitions didn’t stop there. While he pressed forward with his own ventures, he was general manager of the Delta Coal Company heading up the company’s daily operations. His role effectively cemented him as one of Pittsburgh’s premier businessmen. At the same time, he and his wife Anna were fast becoming prominent among the Black community and affluent circles of Pittsburgh.

In doing so, he earned notoriety in papers across the country. The Langston (OK) City Herald’s June 15, 1893 edition had this to say:

“C.W. Posey of Munhall, PA., is the first Negro granted a Chief Engineer’s license to run a steamboat on the Mississippi River and its tributaries. He is now general manager of the Delta and Cyclone Towboat Company. He is also a stockholder in that company.”

Building an Empire

No sooner had he taken the reins of the Delta Coal Company when opportunity again knocked for the already successful businessman. If his previous successes were not enough to prove his role as an American industrialist, the creation of the Diamond Coke and Coal Company would. Under his leadership, the company employed as many as 1,000 people from Pennsylvania to the Great Lakes States.

His empire now included supporting another magnate’s empire – Andrew Carnegie’s U.S. Steel. Using ships on the Great Lakes and steamboats on the rivers, Posey transported iron ore to Pittsburgh for Carnegie. The undeniably lucrative deal coupled with smart investments and business acumen propelled him to great wealth. His close working relationships with business partners in a predominantly white-dominated world earned him credibility and financial opportunities, but more importantly a near unanimous standing among them as a trusted and reliable businessman.

Posey, whose reputation preceded him, was soon recognized as a preeminent boat builder and captain, earning him the nickname “Commodore Posey.” Over the course of his career, the veteran riverman built 41 steamers that operated throughout the inland rivers. Well-built and highly versatile, these boats served various river ports and industries.

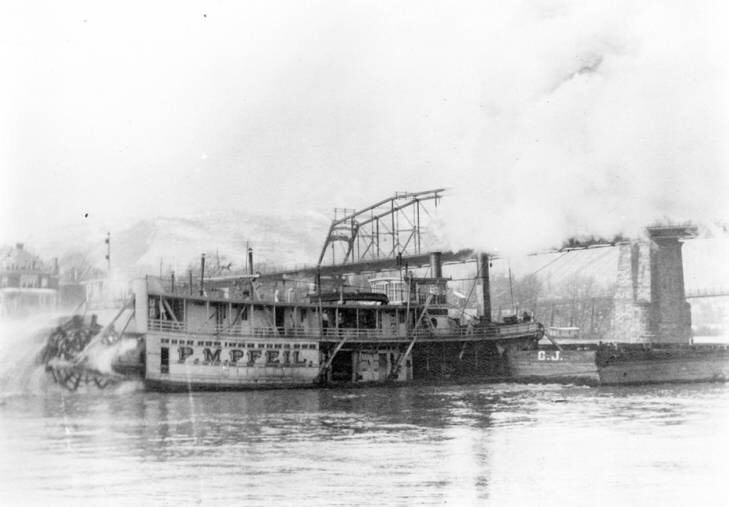

While freight bill records for Posey’s companies are rare, photos of his boats in Wheeling exist and historians agree that his were among the many that came and went from Wheeling on a daily basis.

“Commodore Posey’s boats were highly admired by the river fraternity and frequently towed coal down the Monongahela to Wheeling and other cities who needed large amounts of the product. While there is no photo showing Posey in Wheeling, we know from his early days of working on the river that he would have visited it at various times. It’s hard to find a riverman who doesn’t know a city where his boats are going,” said Jeff Spear, president of the Sons and Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen.

Fellow river captain E. A. Burnside when writing to his company’s home office regarding a prospective boat purchase in 1907 said, “Capt. Posey is a colored gentleman, a river engineer, part owner of Diamond Coal Company., Pittsburgh… Posey made considerable money trafficking in old boats, building new ones, selling, etc. Made it all in the river business around Pittsburgh. He builds very good poolboats, some of the best ones around Pittsburgh.” Note: poolboats were specifically built with low pilothouses positioned on the front of the boat so as to navigate the numerous low bridges found on Pittsburgh’s three rivers.

Out of all the boats built by the Commodore, the Tornado was probably the most famous. Owing to his well-organized and efficient planning, the boat was built in only 54 days. While her record-breaking cargos of steel products and coal garnered her significant press, it was her midnight grounding during extremely low river conditions on Possum Creek Bar below Clarington, Ohio on August 1, 1908 that made her famous and a spectacle to curious onlookers who came from near and far.

For over three months the vessel sat perfectly level atop the notorious sandbar – a testament to her exceptional construction by Posey. Tarps were hung along her wooden hull and over her paddlewheel to keep her hull seams and paddle bucket boards from drying out. At long last on the day before Thanksgiving 1908 the river rose and the Tornado was afloat once again, none the worse for the wear.

Making Headlines

Newspapers of the period reporting the weekly river news seemed to give the Commodore his due credit.

In 1901, the Colored American magazine highlighted the improbable entrepreneur’s success saying, “The question of color never enters his business; he is a boat builder and master of his profession. Pittsburgh needs boats; Posey supplies them; hence his success… In person, Mr. Posey is a man of robust features, genial habits, and never in too big of a hurry to greet you with a smile.”

As was rightly stated in the S&D Reflector by the late Capt. Fred Way, Jr., “Captain Posey was held in very high regard for his boat design not just in Pittsburgh but up and down the river.”

As an investor he also held financial interests in numerous areas, including banks and the Pittsburgh Courier Publish Company, which was a prominent African American publication, of which he later became president. He also invested in the Homestead Grays, which was a team in the now defunct Negro Baseball League and one in which his famed son, Cumberland “Cum” Posey, Jr., would become a renowned player and eventual owner.

A Forgotten Legacy

Like some of his wealthy industrial contemporaries, Commodore Posey was a civic-minded individual with an active role in a number of communities and organizations, including the African American chapters of the Free Masons and YMCA. However, his most notable community achievements were made possible through his participation and support of the Loendi Social and Literary Club. The affluent club was made up of Black businessmen whose goal was to improve the communities in which they lived.

In 1917, the Commodore’s good fortunes ran short when he lost his wife Anna at the age of 55. Her distinction among the Homestead and Pittsburgh Black communities provided great support to him throughout his career. In 1919, Posey would remarry to Homestead resident Bessie Page.

By the end of his life on June 5, 1925, Commodore Posey had greatly impacted the community around him and was a pillar of African American culture and progress. His successes rivaled that of Andrew Carnegie, whose similar rags to riches story is perhaps the central reason why both men widely respected each other and worked so well together.

Yet, unlike his contemporaries whose vast empires and legacies continue to garner recognition and respect, those of Commodore Posey and his wife Anna are now gone, except for her Aurora Reading Club, which is a Black women’s literature organization that continues today. Even in Homestead and Pittsburgh, little remains of the legacy the Posey’s built.

The Ultimate of Ironies

It was, in part, due to Wheeling’s consumption of coal and ore that contributed to his successes – and what an irony that is when we consider Wheeling’s own history.

Only just decades before, a man of his color would have been sold and traded as property along with many other enslaved people as part of the city’s economy. Decades later, that very same city’s economy was now dependent on Cumberland W. Posey, a Black man born of freed slaves, and whose vessels came with coal and other products.

His improbable rise to one of the wealthiest Black men of his generation remains one of the great forgotten stories of the industrial age. But we should each be reminded that this nation’s industrial triumphs are not exclusively attributed to white men. Commodore Posey deserves the recognition that has long been given to Rockefeller, Carnegie, Mellon, Vanderbilt, and Morgan not only for the role that he played in America’s industrial rebirth and his acts of philanthropy but for the barriers he broke in doing so.

• Taylor Abbott is the treasurer of Monroe County, Ohio, and was born in Wheeling, West Virginia. He is a graduate of Ohio University and is co-founder and president of the Ohio Valley River Museum. He serves on the board directors for the Sons & Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen and is an advisor to the Ohio River Museum in Marietta, Ohio. He enjoys hiking, travel, historic preservation and restoration work. Taylor resides in Clarington, Ohio, with his wife Alexandra in a former church they purchased in 2016 and renovated into their home.