Can you imagine the chaos if all of the street names and house numbers changed in Wheeling? The confusion, the misdirection, the lost residents? In July 1873, the Wheeling City Council passed an ordinance to do just that—rename all of Wheeling’s street names and renumber all of the houses.Why Bother?

In 1873, Wheeling had only officially been an established town for less than eighty years—and with street names for only a fraction of that time! So, why rename all the streets and renumber the houses?

Answer: The Postal Service.

While mail service had been around in the US for about a century—since Benjamin Franklin was designated the first postmaster general in 1775—the late 19th century saw significant postal reform.1 In the early 1870s, Wheeling reached the 20,000 population requirement to be eligible to receive free city mail delivery.2 But, the catch was that they had to rename all the streets and renumber the houses to make mail delivery more straightforward and efficient.

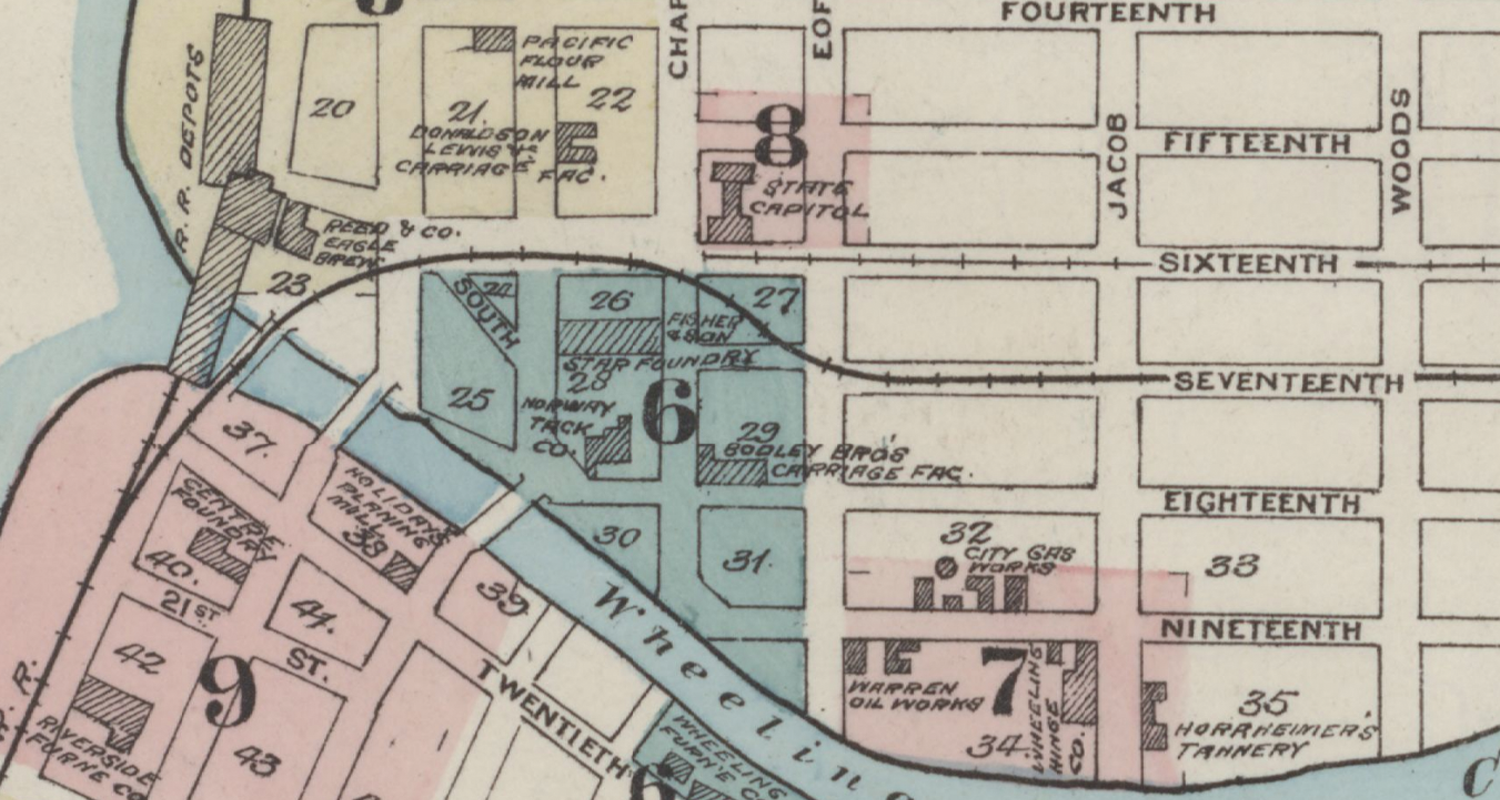

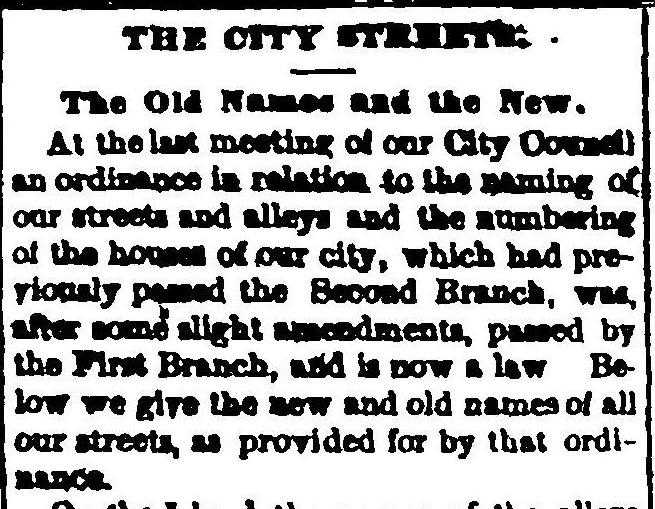

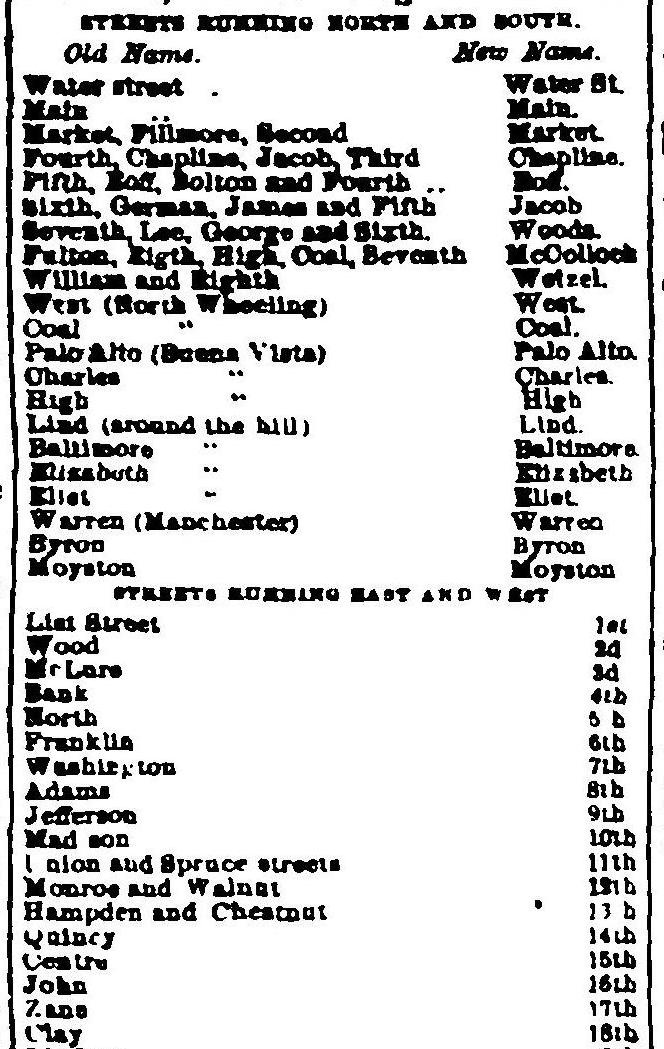

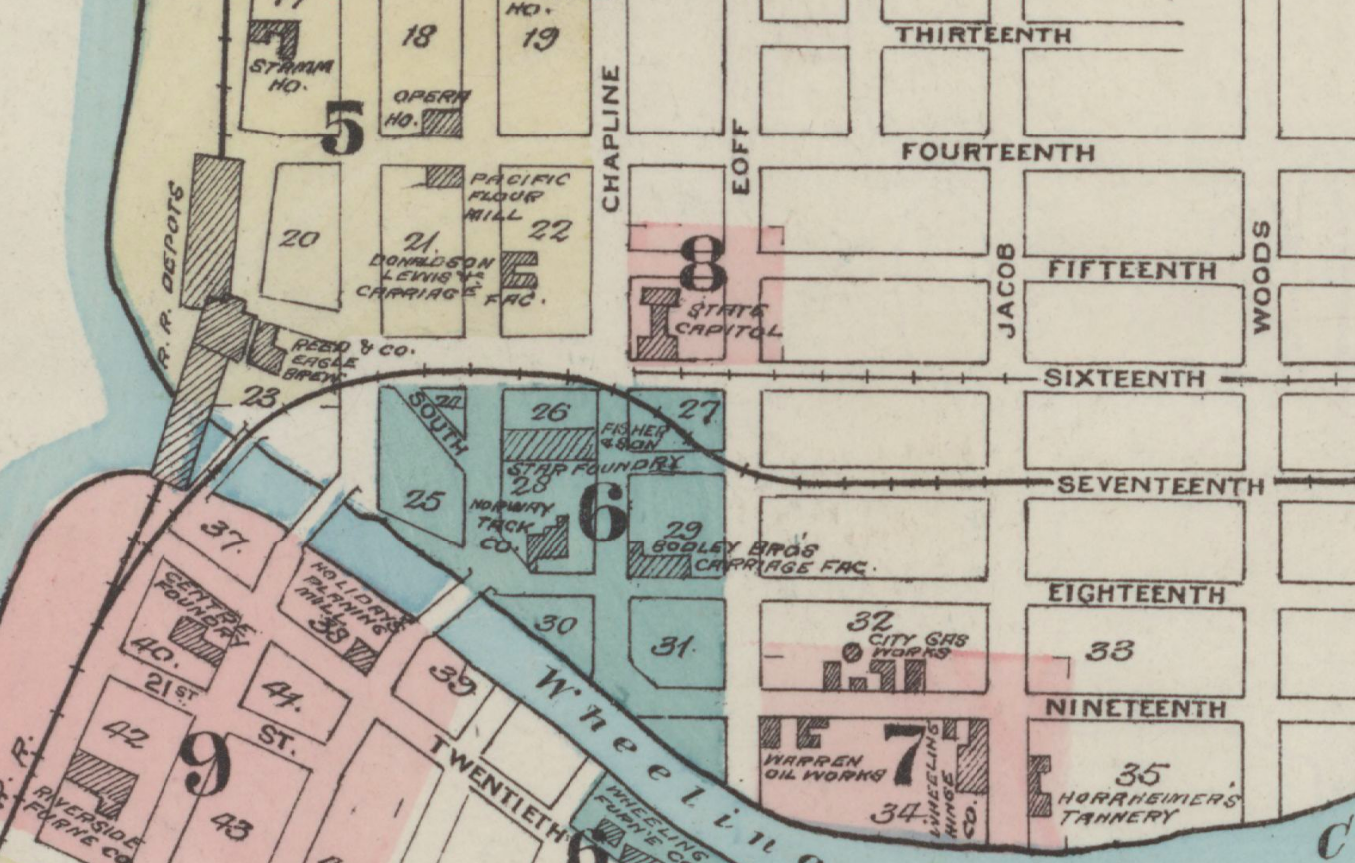

As Wheeling grew as a young city, streets were named as the boundaries expanded—there was no original systematic planning. Many of them had been named after notable men in US history, such as Washington and Jefferson Sts., or prominent Wheeling families such as Zane St. In alignment with US fashions at the time, tree names such as Oak St. or Walnut St. were popular, especially in South Wheeling. For the most part, the majority of the streets that were renamed were those that ran from east/west. They were renamed with numbers, such as 1st, 2nd, all the way up to 48th Street, to make it easier for postmen to orient themselves.3

The decision to change the street names and renumber the houses was about two years in the making. As a responsibility of Wheeling’s City Council, a “Special Committee on Renaming the Streets and Alleys and Renumbering the Houses” was created as far back as November 1871.4 This committee presented its findings to the mayor and the rest of council the following February, 1872, but it took over a year until July 1873 for the ordinance to finally be passed.5 Talk about bureaucracy…

It got to the point where the Wheeling Intelligencer editors were publishing op-eds urging the city council to make a move, arguing that “any of the various methods that have been proposed would be far preferable to the present chaotic condition of the names and numbers now existing.”6 When the council finally passed the ordinance in July 1873, the Intelligencer was one of the first to declare its new address: “The Intelligencer hails this morning from Fourteenth street corner and alley B.”7 They also published long lists explaining every change to the public. However, sometimes change takes a while to catch—in the city directory for the year after, they still listed the old names alongside the new.

What About Other WV Streets?

As one of the five largest cities in West Virginia, Wheeling’s streets were named during the first half of the 19th century…and then renamed them within the same century. However, many rural areas of West Virginia did not even have street names or house numbers until as recently as the 1990s!

As part of a lawsuit settlement with Verizon, as compensation for inflating rates in West Virginia, the state got Verizon to pay millions of dollars to “put West Virginians on the map.”8 However, it was easier said than done. To name (or rename) one street generates dozens of discussions—to name hundreds was a headache. According to author of The Address Book, Deirdre Mask, “each West Virginia county cultivated its own naming strategy. Some took an academic approach, reading local history books to find appropriate names. Phone books borrowed from Charleston and Morgantown were brought to the office. When one addresser was looking for short names that would fit on the map, his secretary scoured Scrabble websites.” In one of Mask’s best stories, the addressers ventured out looking for inspiration, met a “hot” widow, and named her street, “Cougar Lane.”9

Wheeling’s Streets Today

In an article for The Washington Post where he tried to track down the most popular street name in the entire country, Jeff Guo commented that “road names are pieces of history.”10 Here in Wheeling, the change of the street names is merely another chapter in that history. Yet, the older names still persist. For example, visitors and residents alike may scratch their heads over the name of the Monroe Street East Historic District, located at the corner of 12th and Byron Streets.

Just like back in the 19th century, to name a Wheeling street today, you still have to go through the local city government. According to the most recent Wheeling City Charter, “all street names shall be subject to approval by the planning commission,” which reports to the city council.11 Yet, there are still street name squabbles. Most recently, residents got into a tiff over duplicate street addresses between Elm Grove and Bethlehem.12 Who knows…maybe in another hundred years, Wheeling will have completely different street names!

To see the before and after street names in Wheeling, check out this pdf list from the Ohio County Public Library!

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “Significant Dates,” United States Postal Service, accessed May 4, 2021, https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/significant-dates.htm.

2 “Joseph Briggs and the Free City Delivery,” Smithsonian National Postal Museum, accessed May 4, 2021, https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/customers-and-communities-serving-the-cities-city-free-delivery/joseph-briggs-and-the.

3 “The City Streets,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 11, 1873, p. 4.

4 “City Council,” Wheeling Intelligencer, November 22, 1871, p. 4.

5 “Report of Special Committee on Renaming the Streets and Alleys and Number the Houses: Laid on the Table and Ordered to be Printed February 20, 1872,” Wheeling Intelligencer, February 22, 1872, p. 4.; “Progress,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 9, 1873, p. 1.

6 “Will It Ever Be Done?” Wheeling Intelligencer, April 21, 1873, p. 4.

7 “Progress,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 9, 1873, p. 1.

8 Deirdre Mask, The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal About Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power, (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2020), 6.

9 Ibid., 7.

10 Jeff Guo, “We counted literally every road in America. Here’s what we learned.” The Washington Post, March 5, 2015, accessed April 29, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2015/03/06/these-are-the-most-popular-street-names-in-every-state/.

11 “1307.02 General Design of Streets,” Codified Ordinances of the City of Wheeling, West Virginia, 1984, amended October 20, 2020, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/wheeling/latest/wheeling_wv/0-0-0-19794.

12 Eric Ayres, “What’s in a Name? Maple Lane in Elm Grove Having an Identity Crisis,” The Intelligencer, April 5, 2021, accessed May 7, 2021, https://www.theintelligencer.net/news/top-headlines/2021/04/whats-in-a-name-maple-lane-in-elm-grove-having-an-identity-crisis/.