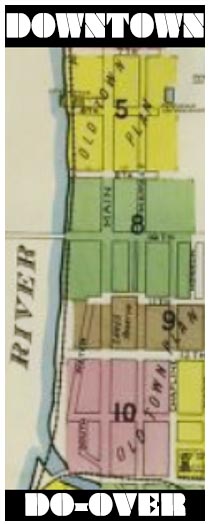

Editor’s note: The Downtown Do-Over series is taking a close look at the ongoing revival of Wheeling’s city center. In today’s story, Weelunk looks at what it actually takes to restore historic structures. Viewpoints include Mayor Glenn Elliott, architect Vic Greco and Jake Dougherty, executive director of Wheeling Heritage. May is Historic Preservation Month, established in 1973 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Editor’s note: The Downtown Do-Over series is taking a close look at the ongoing revival of Wheeling’s city center. In today’s story, Weelunk looks at what it actually takes to restore historic structures. Viewpoints include Mayor Glenn Elliott, architect Vic Greco and Jake Dougherty, executive director of Wheeling Heritage. May is Historic Preservation Month, established in 1973 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

“After he realized I wasn’t dying, he just laughed hysterically,” Dougherty remembered of the collapse, which dropped him hip deep.

The laughing wasn’t callousness, he noted, just evidence of the camaraderie among those men and women who are either in the throes of crashing out plaster or seeking funding for a project.

“Nothing can scare us,” Dougherty said, already able to laugh about it himself.

Like Elliott — who lives and practices law in an 1892 building he and girlfriend Cassandra Wells are ripping up and restoring floor by floor — Dougherty has seen worse in his work for a non-profit dedicated to facilitating historic preservation. He pointed specifically to Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP.

Now, Wheeling’s riverfront branch of the international law firm is full of industrial/skim-latte/open-space splendor. Before the restoration, it was full of, well, other things.

“Nothing in the city is as bad now as Orrick once was,” Dougherty insisted. “There were trees growing out of the mortar. There were birds in the building. … It was structurally unsound.”

So, when the energetic 29-year-old looks around downtown, even from the viewpoint of a collapsed floor, he sees possibilities. Asbestos? Dodgy roofs? Wiring close to setting fire? Skilled developers simply know how to deal with such things.

“It takes a lot for a building to be at that point (of needing to be torn down rather than restored),” Dougherty said. “It’s about finding the right person who has the means, the experience and the desire to bring it back.”

RAISING THE DEAD

Often, that right person is more like a team. Mayor Elliott, in a recent interview with Weelunk, credited such a group effort for resurrecting Orrick, originally Wheeling Stamping Company. Players from government, non-profit and for-profit sectors came together to make it work.

In the last year or so, there is another player on the team, one who is quickly moving into MVP status, Dougherty added.

Effective in 2018, the state of West Virginia upped its historic rehabilitation tax credit from 10 percent to 25 percent. That means one quarter of qualifying restoration expenses (as in “historic,” not something like vinyl siding slapped over a brick façade) can be directly deducted from an owner’s state tax bill. In some cases, Dougherty explained, the state tax credit can be sold to another party to free up more cash for an ongoing project.

Developers can also tap into a similar 20 percent tax credit from the federal government, a credit Dougherty said local Congressman and restoration advocate David McKinley, R-Ohio, has been key to keeping alive.

Together, those credits can make a restoration project financially competitive with new construction, he noted.

Architect Vic Greco, principal of Mills Group, said that was true for Boury Lofts. Greco had assessed the arch-windowed building probably a half dozen times for potential restoration before tax credits and the right developer (Woda Cooper Companies Inc.) came together in the last handful of years.

“It took experienced developers and very creative financing,” Greco said of tapping into both the dual tax credits for historic restoration and other incentives linked to the creation of new housing and commercial space. “It’s great to see … (but) it was not at all easy.”

Easy, no. But, Elliott believes that the restorations are also better for the local economy and environment. Keeping the high-quality materials in use means less waste is going into landfills and fewer resources are being used to make lower-quality replacements. Also, with restoration, Elliott noted more money goes into labor rather than supplies.

DEVIL IN THE DETAILS

Both Greco and Elliott know how not easy historic preservation is on personal, as well as professional levels. Greco — when not working on projects like Boury Lofts, Stone Center, Kaley Center and the Flat Iron building — is constantly tweaking his own home in the Woodsdale/Edgwood historic district.

“I’m handy,” he laughed. “You’re on project number 465, and project 200 needs to be redone because something has rotted through.”

Elliott can relate.

After returning to his hometown (after working for the late Sen. Robert C. Byrd in Washington, D.C.), Elliott bought the 1892-built Professional Building on Market Street. It’s now his home, the base for his law practice and a source of rental income. Elliott is renting space to other entrepreneurs as he and Wells restore it.

That has meant personally ripping out layers of drop ceilings, repairing plaster and dealing with left-behind oddities such as an early 1900s doctor’s table and a massive vault in the basement for which he has no combination. “I’ve never closed the door,” he said with a smile.

Not to mention fire-code issues. Elliott practically groans at that thought.

“Each floor dated to a different vintage, depending on when it was most recently renovated,” he said of the Professional Building. “I know the challenges that these old buildings face. (They) weren’t built for 21st century fire codes.”

In particular, issues like entrances and exits and sprinkler systems can raise economic difficulties. New sprinklers have to tap into city water lines, for example, at a fee that can be prohibitive. At least one property, not owned by Elliott, faced a $50,000 tap-in fee, he said.

The city already has a program to match investments in building façades and roofing. He could see a point at which there are also incentives to help with the tap-in fees or other fire-code efforts.

Difficulties aside, Elliot said becoming a redeveloper has been a good thing.

“I credit buying that building with really tuning me in to the opportunity of downtown Wheeling,” he said. “(When I was a child) I came downtown every Saturday with my grandmother and did the circuit — Stone & Thomas … Louie’s Hot Dogs. But, I never looked up.”

He is so convinced of potential, in fact, he’s since purchased the Professional Building’s two neighbors. This was partly to ensure the stability of the main structure and partly to preserve the overall neighborhood feel, a “whole block” component Dougherty said is critical for historic authenticity.

Elliott and business partners now own some 30,000 square feet of space. One of the side buildings already has tenants. The other is, “basically a shell,” at this point, but a stable one.

AN AUTHENTIC FUTURE

Stable is what it’s all about, Dougherty noted. A Millennial himself, he said his age peers want to locate in cities that offer a sense of “authenticity” and permanence in a world that is constantly changing. Having grown up in Wheeling and worked in the nation’s capital, he sees this city as hitting a critical sweet spot.

“That’s what makes Wheeling unique,” Dougherty said. “It’s a small city that feels bigger than it is and can be attractive to people from all over the nation.” Bigger city folks don’t feel hemmed in and small-town folks don’t feel overwhelmed, he noted. “It’s this perfect little niche.”

Elliott agreed, commenting that buildings like his home base are not being constructed anymore.

“They (bank that constructed the Professional Building) did not need to ship down 600 tons of granite from Maine,” Elliott said. “They wanted to make a statement. We’re going to be here forever.”

As it turned out, the bank only lasted until 1919, but the building lives on. Elliott sometimes looks out his windows and sees people taking pictures of the site.

“You never see anybody taking a picture of a Best Buy store,” he noted. “Our architecture is something we lose at our peril.”

“You never see anybody taking a picture of a Best Buy store.” — Mayor Glenn Elliott Jr.

Architecture aside, the downtown is just becoming fun, he added.

“I love living downtown,” Elliott said. “You see people walking around, and you see people walking their dogs. It’s been more of a community.”

All three men agreed that one aspect of that community simply must be the restoration of the former Wheeling-Pitt Steel building. The city’s tallest building, at 20 stories, is being eyed for market-rate apartment redevelopment by an experienced firm from Ohio — if the city will pay for a parking garage for future residents.

As that project works its way through the governmental system — or doesn’t — Greco said he would also like to see the city do additional beautification at the point where I-70 exits into the downtown community.

“To me, that’s our front door,” Greco said.

TEARDOWNS HAPPEN

While there are many forces at work to restore, demolition is sometimes the better option, all three men also noted.

Elliott pointed out that the Health Plan insurance company’s new headquarters — the first new commercial construction in the downtown in nearly 40 years — required the demolition of a handful of older buildings that weren’t in the greatest of repair even though they were occupied.

Viewing that demolition as an investment, the city stepped in to relocate the businesses that were displaced, and Elliott is happy with the results. “Seeing a shiny new corporate headquarters in downtown is definitely a shot in the arm,” he said. “It’s changing the conversation. It’s got people excited.”

He also noted that The Capitol Theatre, which is a historic building, is technically a rebuild, as well. There were a handful of smaller buildings on the site that were demolished for its construction. Elliott considers the theater the far better outcome.

Also off the cityscape is the building where Dougherty fell through the floor. It was demolished not long after.

“I had the last laugh,” he said.

• A long-time journalist, Nora Edinger also blogs at noraedinger.com and Facebook and writes books. Her Christian chick lit and faith-related non-fiction are available on Amazon. She lives in Wheeling, where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household.