While looking back on this experience with the hindsight of age and passage of time, I realize these summer experiences were precious episodes in my life. We never did the “usual” thing — ever. I don’t know of any other trio of children who owned their own geology picks.

When Rt. 2 just north of Wheeling was undergoing one of its widening projects in the 1950s, Dad was in his glory. He piled us in the family car, and we were off to find a dinosaur bone … (or so we hoped). With picks in hand, we gleefully chipped away at the newly cut rockface, finding crinoid stems and other small fossils. The three of us were convinced we would find that mastodon tusk, but Dad said it wasn’t the right kind of rock formation. He had spent three years of college studying to be a paleontologist before switching to pre-med, so his knowledge of everything rock-related was awesome.

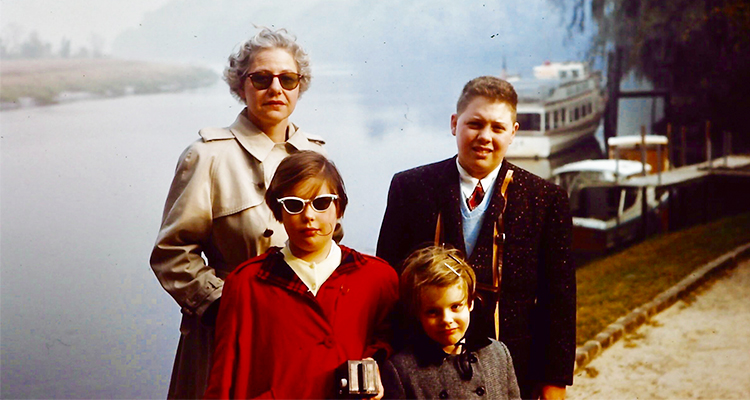

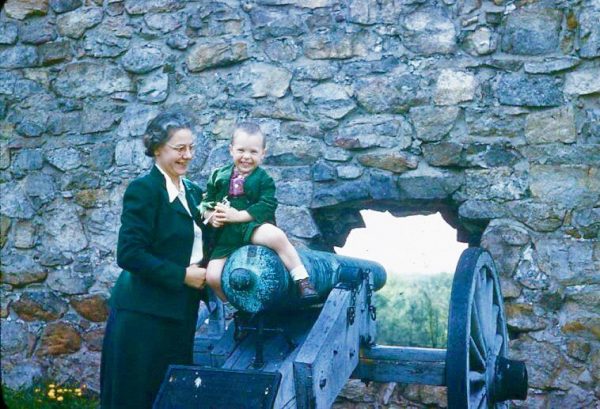

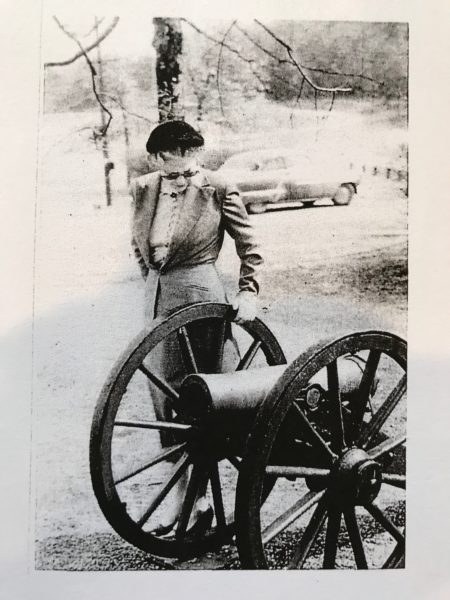

Back to heavy artillery. Sometime in the early- to mid-1950s, Dad decided that he would undertake the monumental, overwhelming job of finding and cataloging every extant Civil War-era cannon in the eastern United States. This meant road trips. Lots of road trips. Long before the day of the internet and instant information, the only way to find a cannon was to visit every battlefield and town square in the world — or so it seemed to three children, aged 12 (Jimmy), 9 (me, Anne) and (Posy), 6. Frequently, the guns had been moved around from location to location without regard to place of origin or even which side they were supposed to be on. Many were scrapped for iron during subsequent wars.

I’m not sure where we started this quest, probably Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. To set the stage, I have to talk about the car in which we undertook these pilgrimages.

Dad always drove a Cadillac just as most doctors did in the old days. He later switched to a Chevrolet when Mom pointed out that maybe his patients would pay their bills faster if he drove a more modest car. (They did.) Back to the Cadillac. It was big and wide. My older brother and younger sister and I were all chubby, bordering on fat. No car was wide enough to prevent us from bumping into each other, many times on purpose. “He’s touching me” would be our cry when an elbow would brush another elbow. Our two weary parents coped the best they knew how.

They coped by smoking cigarettes … Dad, unfiltered Camels, Mom some sort of filtered brand.

Backing up a bit — there was no air conditioning in the car, and most of our trips were in the summertime, well south of Gettysburg on two-lane roads as this was pre-interstate. Also, we were all three prone to carsickness. Picture three, whiney, fat kids in the backseat of a car with both parents smoking like chimneys with the windows open in miserable heat. When all the windows were open, guess where the smoke went? Into the backseat. Many times, one of us in the rear seat would call out, “I’m going to throw up.” With that, Dad would pull over, and two back doors would open — very quickly. Even though we didn’t have a cousin Eddie to visit, Chevy Chase and his family had nothing on us.

We would play road sign games, the kind that are ancient history now. In the day when we sought to while away the miles when we weren’t in a Dramamine stupor (it did help with carsickness), those games helped. And those Stuckey’s signs. They promised relief in a series of signs posted about a mile apart along every road throughout the South. Stuckey’s (founded in 1937 in Georgia) and Howard Johnson’s were staples in a day in which there were really no big restaurant or motel chains nationwide. Wherever we landed, Ho Jo’s always had the same food, no surprises and, of course, the ice cream. As I said, we were chubby, and that ice cream topped with caramel or chocolate, whipped cream and a cherry was something we looked forward to more than you would believe. We stayed overnight, in the deep south in some pretty questionable motels, most with Spanish sounding names and swimming pools with green water. The doctor father, of course, nixed the after-dinner swim.

Dad had a definite plan as far as how he would record or catalog each gun we encountered. First of all, we had to get written permission from the National Park Service and each Civil War battlefield superintendent to allow us access to the guns, not all of which were on display. I’m sure Dad was viewed as some sort of nut in those days by some, but most of the park historians were glad to help us roam around their battlefields at will and, occasionally, even to scrape black paint from the guns when necessary.

Mom was the one trusted with the clipboard. The drill went this way: Dad would recite the numbers, letters, etc., from each cannon, noting their location and placement on the piece. Mom would record everything. A rite of passage was to be allowed to hold the clipboard and transcribe the called-out information. My brother and I were eventually entrusted to do this precious job.

The boredom we (children) experienced was punctuated by the overwhelming realization that these huge guns had killed people, lots of people in horrible ways. I was always a sensitive child. Bloody Pond at Shiloh is still haunting to this day. When we visited it, it happened to be an overcast, heavy day. I could imagine the bodies in the water and the carnage that caused the pond to have its name.

Chickamauga, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Fort Sumpter and Antietam were just some of the places we ambushed with our clipboards, flashlights and penknives. In the mid-’50s, there wasn’t a great deal of money available for the upkeep or interpretation of these battlefields, not even to cut the grass. Vicksburg, Mississippi, was a memorable journey through 5-foot-high Johnson grass. The blades seemed as sharp as knives, and it was everywhere. We had to traipse through lots of this to find the cannons.

Edwin Bearss, renowned historian and later chief historian of the National Park Service, was our guide. He was park historian and, in those early days, he even wore a park ranger uniform. He was devoted to the cause of restoration and interpretation of Vicksburg and welcomed our motley band of invaders with gusto and eagerly led us to every gun in the park. Much later, his comments and insights were featured in the iconic Ken Burns series on the Civil War.

I came away from these childhood trips with a knowledge not shared by most of my friends — make that any of my friends. I knew what a cascabel was, where the trunnions on a gun could be found and how much effort it took to scrape black paint off the muzzle of an antique field piece. I didn’t have a tanned body after two weeks at the beach. I didn’t have a collection of seashells. I had learned more history than I realized at the time. I had felt the appreciation of human sacrifice. Most important of all was working toward a goal bigger than my need for a “vacation.” We worked together to further our father’s mission; squirming in the back seat of the car, fighting, throwing up aside — we were a team.

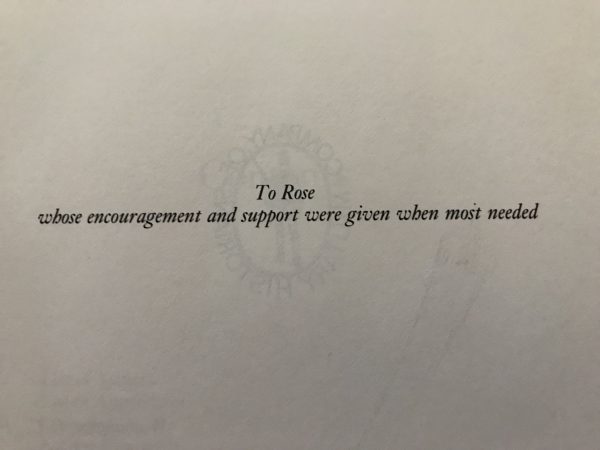

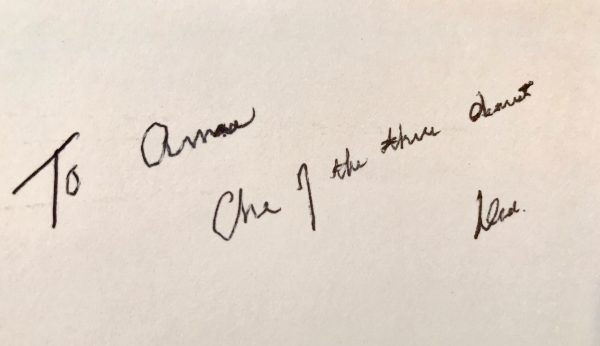

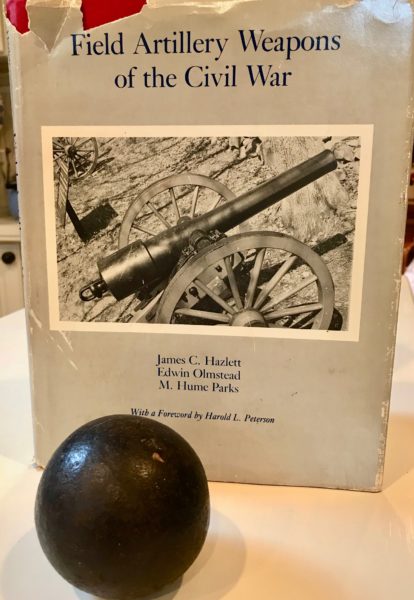

After several years of this kind of research, Dad, with the help of two other historians, Edwin Olmstead and M. Hume Parks, put together their particular roles in this quest into book form, Field Artillery Weapons of The Civil War. The dedication is a testament to Mom’s role and reads, “To Rose, whose encouragement and support were given when most needed.” Dad signed my copy, “To Anne, One of the three dearest.”

Harold L. Peterson, in his foreward, said, “… the authors have done a tremendous job in sorting out and locating the types, sizes and variations of these historic cannons. It has been a task requiring years of dedication, laborious field work and mental gymnastics.” I have the original manuscript and treasure it.

Fast forward many years. After Dad’s death in 1990, his Civil War collection of artifacts and paraphernalia were left to his children, those same people who had been blessed with the opportunity to have been with him during his quest. Among the many things I inherited were his grandfather’s green silk medical sash (he was a surgeon with the Union Army), a bayonet, a saber, an 1850 salute cannon and assorted cannonballs. Add fuses in their tiny paper boxes, and I probably had enough gun powder to start my own war. At the time of the distribution of these treasures, no one was particularly concerned about the safety of having cannonballs lying around. My brother opted out of taking any. My sister and I ended up with all of them of various sizes; some were large.

Years later, when I started having curious grandchildren capable of rolling and throwing balls around, I became concerned about the brass bucket in the living room full of very heavy balls. I decided I needed to calm my fears about having them in the house. At the time, there was no ATF representative in the area. Former Ohio County Sheriff Tom Burgoyne was contacted and suggested calling the state police for an evaluation of the ammunition. We did.

A very nice off-duty state policeman called one day close to Christmas. He was on his way to the mall to shop for gifts for his family. After taking a look at the stash of explosives, he went to his Jeep and brought back an orange crate full of rags. He inspected each cannonball carefully and explained why he was concerned about its particular presence in my home. I watched him wrap all but one in rags as he arranged them carefully in his crate. He told me that they were full of gunpowder. Old gun powder that had become more fragile with age.

I asked him what he was going to do with them, and he explained that they would be destroyed safely. I asked why they couldn’t be donated to a museum, and he said they would not be permitted to accept anything that qualified as live ammunition. I asked if they would have been a problem if dropped by a toddler and he said, “No, but, if you had had a fire in the house, your end of the block would have gone up.” I had visions of these red-tagged cannonballs being posted on some Civil War black market websites. After all, these were genuine, live, antique cannonballs … probably worth a lot of money to someone. Putting that image out of my head, I thanked him for helping us. I was allowed to keep a 3-inch (in diameter) solid shot. It sits in a special place on the hearth today.

During a conversation with my sister, who lived in the D.C. area, I told her about my experience and mentioned my concern about her cannonballs. She had as many, if not more, than I. Several days later, she called her ATF. Within an hour, two bomb trucks pulled up in front of her Springfield, Virginia, condo and several men in bomb attire filed into her house. They removed each cannonball one by one, taking them to one of the trucks. They came back with X-rays of each one. They were all full of gunpowder.

What could have been a genuine “blast from the past” was averted. Black powder that had endured the century mark and more encased in its iron spheres was now safely disposed of. I’m sure somewhere at a gun range in West Virginia, there were some off-duty state troopers detonating multiple cannonballs. Possibly with a keg of beer close by.

As far as my sister Posy’s haul of artillery shells, I have no clue — but I’m sure it’s classified.