It was the play space for generations of the children of the three streets that bordered Elm Street. Violet Hill, as it was known, provided a grass-covered playground crisscrossed by diagonal paths leading from the brook at the bottom to the road at the top, which was Echo Point Circle.

The creek supplied what all small running bodies of water provide to neighborhood children of a certain age. Water is a draw for humans, whether it be the ocean, a lake or a small stream meandering through a grassy space. Ours was full of minnows, water striders and slippery green slime blanketing rocks that lined the creek bed.

Its origins are high on the hill above Edgwood. If a creek can be said to have headwaters, Elm Run originates from many hillside springs high above the streets below. It meanders through woods, runs parallel to Edgington Lane Hill until it crosses under it and winds through backyards along the way. It crosses under Edgwood Street and follows Elm Street until running under National Road into the Lennox neighborhood. Eventually, it meets Wheeling Creek not far from there.

Every once in a while, when the stream was running fairly full but still clear, we dammed it up to create a small swimming hole. It was usually in the same place, about 25 feet below the footbridge spanning the run where the old streetcar tracks were.

Hours would be spent culling rocks from the creek bed, making sure they were bulky and not too flat, and piling them carefully one on top of the other. We 7-year-olds, who had budding engineering skills, supervised the work and ruled the day. The rocks fit together in a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle of stones, high enough to slow down the flow and create a backlog of clear, cold creek water. It was knee-high for most of the splashers, and no backyard wading pool could hold a candle to it, except maybe one on Birch Avenue that was an old rowboat filled with water. That was pretty awesome.

Occasionally after heavy rains, the stream would become a raging body of heavy, muddy water that flooded roads and basements from Miller Street to Lynwood Avenue. Flash floods threatened residents for many years. Eventually, in the 1960s, the creek bed was dredged, which helped to carry the worst of the runoff, but not all of it. It still has the ability to ruin basements with its brown water and muck.

During my childhood, the hillside above the creek was kept mowed during the summer months. In the springtime, the slopes exploded with blooms of thousands of violets, mostly the purple/blue blooms familiar to most of us, but also white and even yellow. Obviously, the latter two were prized by us more than the more readily available blue ones that carpeted the entire slope.

During my childhood, the hillside above the creek was kept mowed during the summer months. In the springtime, the slopes exploded with blooms of thousands of violets, mostly the purple/blue blooms familiar to most of us, but also white and even yellow. Obviously, the latter two were prized by us more than the more readily available blue ones that carpeted the entire slope.

There were so many violets, it was difficult to pick them without stepping on other plants. We competed for the fattest bouquets to present to our mothers. The violets bloomed for about four weeks every year. Daffodils were sprinkled around the slopes in intermittent clumps as if to add a little variety to our quest.

THE SENSORY PAST

Sensory stimuli experienced early in life are embedded in our brains forever. Smells, sounds and images of all kinds stay with us and, with the right trigger, those sensations return, sometimes with an overwhelming impact. There was the smell of hot sand in a metal sandbox on a July afternoon and then the different smell when water was added. There was the unmistakably acrid smell of burning coal in the air when it got cold enough, especially from the huge complex that housed troubled girls, now a nursing home at the bottom of Edgington Lane Hill.

The basements in most houses were not “finished.” They were where the washing machines were. Dryers were clotheslines strung in the backyard in summer or throughout the laundry room in winter. Starch for my father’s shirts was mixed on a burner in a large metal pot. The ironing board was always up, and the bottle for sprinkling was always on the board. It was a homemade thing using a coke bottle for the bottom and a perforated metal top.

Cotton clothes had to be dampened in order to produce the best result with the iron. I don’t think polyester was around yet. There were the scary, huge cast-iron furnaces in most of the basements with a door that opened into the flames. They all had round tentacles of ductwork leading from the main burner to the rest of the house. And then there were spiders. I never liked that basement.

There was the musty, earthy odor of a pile of leaves in the fall, the crisp sounds they made underfoot on the sidewalk, and the glorious sensation of jumping into a huge pile of gold and red leaves we had made in the yard, sinking right to the bottom (if they were dry), as though it were a colorful cloud. The beautiful hollyhocks that lined the alleys tried in vain to hide the metal Wheeling Steel trash cans with their red labels and smell of garbage.

There were very few fences. Neighborhood dogs seemed to roam in familiar areas and usually came home when called.

The children didn’t need to be called home. We left in the morning and went home when the streetlights came on. Most mothers were home all day, and meals were never an issue. Snacks of graham crackers and Kool-Aid or lunch of peanut butter and jelly in someone’s backyard were taken for granted. Kick the can games on Birch Avenue were nightly occurrences. A variation on other street games popular at the time, it involved a can placed in the middle of the street, scattering of everyone and a countdown of sorts. Then there was the person who got to the can and kicked it first. Fuzzy details at best and not sure about the sequence of events or who would be “it” or why, but it was fun. Usually an after-dinner game, we played until dark.

SCHOOL DAYS

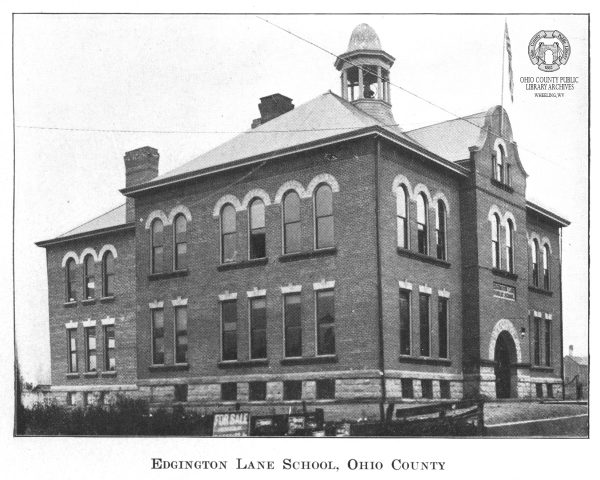

We walked to school, which for the Catholics, was St. Michael’s and for the rest of us was Edgington Lane Elementary. We were warned to stay away from the poor soul who usually ended up sleeping it off in someone’s garage, but we didn’t have the “stranger danger” mantra now so familiar in our vocabulary. We took our lunches to school in metal boxes decorated with images of Roy and Dale Rogers and bought our milk in little pint-sized glass bottles with foil lids. Near the holidays, the lids were either silver, green or red, and we would save them and make garlands out of them for the school tree.

There is no smell quite like the one emanating from an old school. Floor wax, crayons, pencil shavings and chalk dust all gave out their own aromas and, when blended, were unforgettable and somewhat comforting. High ceilings, big windows, long and narrow cloakrooms, hardwood floors and a huge, open stairwell to the second floor, were all part of the ambiance of the home to grades one through five. Miss Clemons was the prim and slender principal, and Pop Miller was the beloved custodian. They were probably both in their 30s at the most, but seemed so old to me at the time.

The basement of the building contained the bathrooms and a large room used for any purpose the rest of the school couldn’t accommodate. Bomb drills were carried out there. On a signal that sounded like a fire drill, we were marched down to that subterranean floor and knelt on the cold cement, curled into a ball with our arms folded over our heads. It was the mid-1950s post-war terror. As though if the bomb dropped, we might stand a chance of surviving it in that position?

The thought of such widespread devastation from the mushroom cloud gave me nightmares for many years and still do. Today’s children heed an alarm that signals a different evil — an active shooter. Their drills are designed to combat a more immediate and personal terror. The enemy at the door changes form but never goes away.

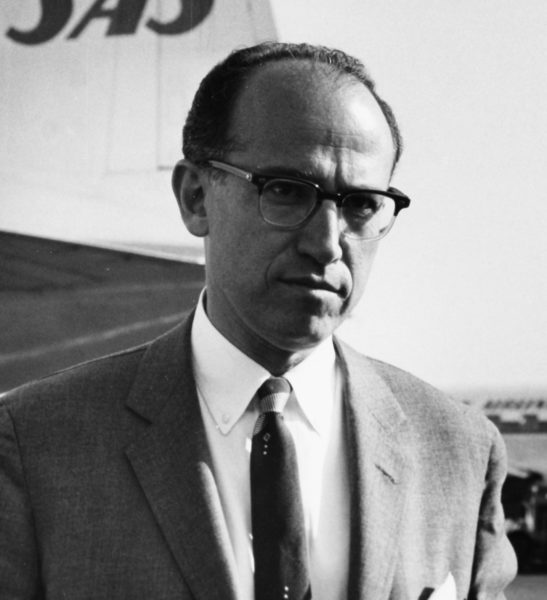

That basement also served as a clinic when Dr. Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine became available. We lined up, one by one, bravely presenting our little arms to the doctor who inoculated us against the deadly, crippling virus. Some of us cried, most didn’t, none really understood the reason we had to undergo this procedure. The dreaded disease was rampant during what were later called the polio summers.

Among other things, we were warned not to use public swimming pools. What seemed to be a harmless cold could indicate the first stages of this killer virus that put so many in “iron lungs” that kept them alive until they recovered. My father diagnosed several cases among his patients. Thank God, they all survived.

Christmas Carols were sung in the stairwell right before the holiday break. No one called them holiday carols. We didn’t know any better, I guess. God and public schools got along better in those days. Once a week, we all marched down the street two blocks to Edgewood Lutheran Church for a Bible class. I don’t think it occurred to parents to protest. We gathered in the basement room for these sessions.

One time, right before Christmas, someone had painted a huge mural on paper of the village of Bethlehem, replete with the stable surrounding sand and sparkling star. I had an epiphany of sorts in that very room. Perhaps it was the warmth after the cold walk, the anticipation of Christmas the next week or the homemade cookies we were given, but I knew at that moment that there was a God.

There was the inevitable transition from home life to first grade. There were no kindergarten programs at that time in the public school system around here. There were private ones. I attended one at Linsly, in the basement of the original gym on the Leatherwood campus. Most of the mothers in our neighborhood didn’t t drive or, if they did, they didn’t have cars, so there were several of us 5-year-olds who went to Linsly in a taxi cab by ourselves. It was, indeed, a different time.

I put up with the whole experience of the smelly gym basement and inane coloring exercises for about two weeks. One morning, sitting up as tall as I could in the back seat, resplendent in my starched smocked dress and braids in my hair, I refused to get out of the car and told the cab driver to take me back home. He did — much to my mother’s surprise and chagrin. I told her I didn’t like it — at all. That was that. I’ve never regretted that decision and am thankful my mother respected my wishes. She should have made me return but, recognizing a strong streak of stubbornness in my German, Scotch-Irish background, she probably decided she had to pick her battles.

A GENTLER TIME

It was the late ’40s and the glorious ’50s. Men returned from the war, it was the age of Eisenhower, there was a boom in building and babies — prosperity was ours. We survived falling off bikes, eating Twinkies, drinking creek water and riding in cars without restraints. Those vehicles were big and, though devoid of modern safety features, they were made of steel — no plastic bumpers or Styrofoam on those behemoths.

Most families had one car and one driver. Fathers came home at six in their suits and fedora hats and maybe had a cocktail before dinner, which was always made lovingly by the stay-at-home mother. They were businessmen, dentists, schoolteachers and lawyers.

My mother baked her own bread and bought fruits and vegetables from the vendor who drove a truck around the neighborhood every week. Trips to town were events requiring hats and white gloves for the mothers. It was always crowded, and the streets were full of shoppers.

We ran outside a lot. Our roller skates were the kind that clipped on our shoes and could be tightened with a key. They had four little wheels. I never mastered them. The first time I put a pair on, the earth turned upside down, and I was on my back. I didn’t like that. I turned my attention to digging to China under the little apple tree beside the sandbox in my backyard. I worked at that for several days and eventually gave up, disheartened.

Oh, those simple pleasures that everyone enjoyed — we were all on the same page. Because our mothers were home, we were too. It was a comforting time, and I realized I was blessed to have lived in a middle-class world — many in those times were not so fortunate.

Those days from my childhood were not necessarily better times, they were just different times. Change is inevitable and can be painful.

In 2019, I look outside my front door on a warm summer day in Woodsdale, and there are no children playing ball in the street, no children at all. They are in daycare or at home plugged into some electronic version of reality. I’m not sorry that I knew how make a mud pie, was dared to taste it and did, got excited about digging to China or knew how to dam up a creek.

Our childhood pleasures are considered primitive and rather naive by today’s standards, but we had so much more than what met the eye.

We could run outside and, within five minutes, summon enough friends for a pick-up ballgame in the street. We took pleasure in raking leaves, making snowmen and buying wax lips and penny candy at the corner store. There was a sense of community not dependent on a hand-held device. We made friends in person, and we called each other on a phone and spoke to the operator down the street and gave a three-digit number in order to do so. We were “Woodsdale 304.”

We walked to the neighborhood movie theater without our parents to watch “Old Yeller” and the like without fearing a shooter suddenly appearing in the room. The worst thing we feared at the Mayfair Theater was a case of ringworm from the seat headrests.

So much has evolved in our world in the last 60 years. Yesterday, I walked down the block where I lived for 10 years. The houses are all still there. Most of the magnificent Elms are gone to disease, and there are more fences in backyards, but it’s basically the same place.

As I passed our house on Lynwood Avenue, I looked up at the window of my old bedroom. I remember watching the dark sky from the other side of that glass on many Christmas Eve nights waiting for a sleigh sighting and, one year, I was convinced that I heard hooves landing on the roof. I’m the only one left of the family of five who lived there. My parents and siblings are all gone now, but the memories of love and life in the cocoon of my childhood will nourish me for the rest of my days.

Stay tuned for Part 2: Echoes … Of Life on Top of Violet Hill

• Anne Hazlett Foreman, an award-winning artist, has been a member of Artworks Around Town for 20 years, having been on the board for the first four years. She also has served as chairman of the Oglebay Institute Mansion Museum Committee; served two terms and was vice president of the West Virginia Independence Hall Foundation; served on the Oglebay Institute Board of Directors, the board of Fort Henry Days and the Wheeling Hall of Fame board; and is a member of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. Foreman is a graduate of Mount de Chantal Visitation Academy and attended Wheeling College and Chatham College. She is married to Robert Noel Foreman, and they have six children and several grandchildren.