Those first impressions of my life as a Mount de Chantal student flooded back every time I visited my alma mater. It was deja vu “all over again.” Increased heart rate, tight throat, the dread that I had gotten myself into something I would not be able to deal with … those feelings never left me.

DAY ONE

The longest one-and-a-half-mile trip I ever took was in the early fall of 1960. It was my first day of my freshman year at Mount de Chantal Visitation Academy. The only other time I had that same sense of loneliness and dread was the first time I was wheeled from the labor room to the delivery room, knowing only that what I was to experience would be interesting and not a little terrifying.

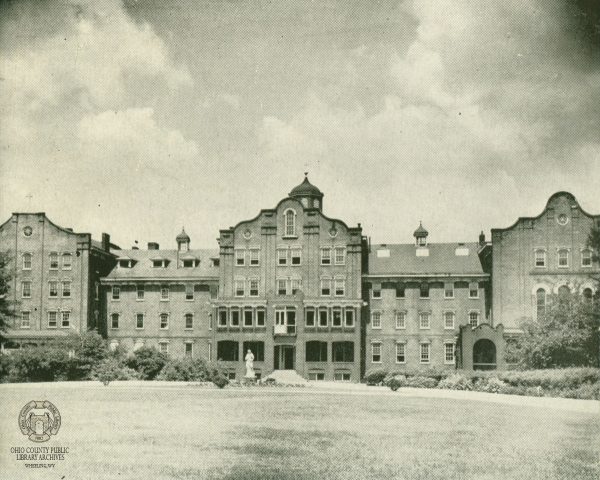

Mom dropped me off in the circular drive, overseen by a statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which freaked me out in many ways, an ominous omen to the presence of more statues inside. We were one car in a parade of cars holding other newbies ready to be sacrificed to that huge red brick building in the name of education.

I passed through the big leaded-glass door into a dark hallway. On either side was a parlor, with a lattice-like wooden screen separating the sisters from their visitors, which was a little unsettling. Another pair of doors led into a bigger hall. The scents of furniture polish, incense and candle wax were strong near the entrance to the chapel.

For a Protestant who was used to rather stark church interiors, a glimpse into the ornately gilded, statue-laden interior was a shock. Statues also graced the large expanse of hallway leading to the then-study hall (later library). Add the nuns, whose attire in those days was still the traditional medieval dress, and I was totally spooked. It was all new to this girl on her first day.

That day, I got my locker assignment, found my classrooms, bought my books and learned that when leaving a room wherever a Sister happened to be, one had to “bow out.” Interesting tradition that, in my old age, would probably be a challenge with arthritis and inner ear balance problems! But in our youth, it was a time-honored nod to the dignity and calling of the women who taught and watched over us every day.

YOUR NUMBER’S UP

Another unique touch was the number system used to call a student when needed somewhere. Each of us had a number. There was a bell near the main stairwell on the second floor. We learned to dread “our number” being rung. This was not the same ear-splitting bell that signaled the change of classes.

In my day, the magnificent open stairwells assured that any of those bells would be heard throughout the building. The stairs were wood with black rubber stair treads embossed with white fleur-de-lis — I assume a nod to the French origins of the Visitation order. You could lean over the banister and look up from the ground floor to the dorm, four floors up. Fire laws later demanded the elimination of all of that and resulted in enclosing of each floor with walls and doors. I guess, in retrospect, the whole structure was a firetrap but losing the grand open spaces was a loss and an insult to the architect who had designed it before the Civil War.

The uniforms we wore had to have been designed by a nun: gray wool box-pleated skirts, white camp-style blouses and forest green wool blazers. Oh, and saddle shoes. Unless you weigh 90 pounds, box pleats are a disaster. In the 1960s, I can’t even remember what girls my age were wearing out in the big world, but I’m sure it wasn’t that ensemble. I do seem to recall friends at Triadelphia High School were wearing Villager brand clothes, flats and sweaters with matching cardigans.

The dress attire was equally as unflattering to adolescent/teenage girls — pastel shirtwaist dresses. I’ve never had a figure or disposition to appreciate a shirtwaist dress. The gym uniform was a red one-piece job that needs no further comment.

Lunch was a highlight for me. I loved lunch. We sat at tables and ate family-style. I remember platters of good food and fantastic breads baked by the nuns. The apple crisp dessert was my favorite. The slightly greenish, ropy tapioca pudding was avoided by most of us with inappropriate comments about its appearance as it was passed around and passed up.

Sister Amy’s after-school store was a destination. Designed mostly for the boarding students to get whatever candy, ice cream or chips they needed to tide themselves over until supper, we day students shopped the last thing in the afternoon, too.

DEVOTION

The sisters were incredibly devoted to developing our minds, nourishing our souls and trying to instill some sort of decorum and polish in our young lives. There were the three o’clock Friday lectures by our beloved Sister Mary Helen. She was as round as she was high, always ready to receive students in her small office off the main floor hallway. The door was perpetually open, as she could look up from her desk and observe her charges at all times of the day. She regaled us about our table manners, talked about the importance of writing thank-you notes, among other things.

One lecture I remember vividly was on friendship. She emphasized how transient our “best friends” at the time were. She made the point that, in 30 years from that time, who would come to our funeral? Wow, talk about a reality check. She was right. We didn’t believe it, of course. I cannot imagine a more difficult population to deal with. Teenage girls, deprived of the day-to-day company of boys, in all phases of puberty, some homesick and all trying to succeed in one of the most difficult and competitive eras in our recent history.

EARLY S.T.E.A.M.

Three years before I got to the Mount, in 1957, Russia launched Sputnik and with it, this nation realized how behind we were in sciences and math. Our algebra, biology and chemistry courses were upgraded it seemed overnight. Add to all of this the Baby Boomers trying to get into college. More students, more intense work.

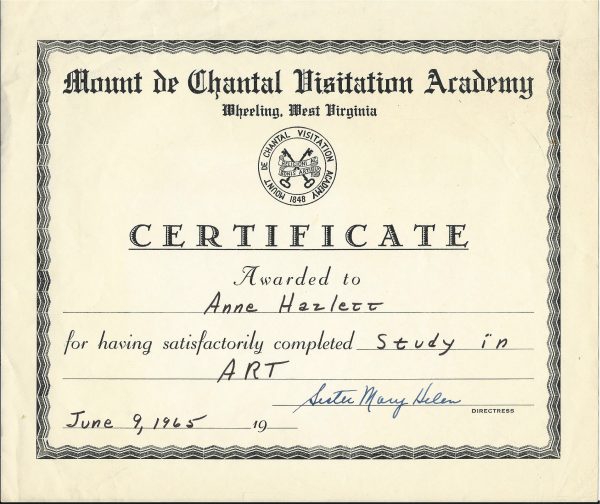

One of those sweet souls who had a special influence on me was Sister M. Cecilia. She taught art. Not the “easy-filler-for-your-course-load art” but a four-year program of atelier studio instruction. At the Mount, a student could opt for extra art or music classes. In that era and before, the Mount was known for its excellence in both disciplines. This was in addition to the normal college preparatory classes. At the end of the senior year, a formal recital or art exhibit was given by those students who had taken on that extra challenge.

Sister Cecilia was about six feet tall, or very close to that and, in her flowing black habit, she was imposing. Her face was always a little flushed and overflowed her wimple a bit. She was awesome. She had lost half of one of her legs in Pittsburgh when she was young in a streetcar accident and had a wooden extension which would clump-clump down the hall when she was approaching. She was the campus St. Francis, always rescuing injured birds, squirrels and any other kind of critter who needed help.

At the very back of the cavernous studio was a black curtain. Behind that curtain, Sister housed her charges. Day students would volunteer to bring her ground raw meat so she could cook it over her Bunsen burner for the baby birds. We were never allowed behind that curtain. I have a feeling this practice of caring for little creatures didn’t sit well with her community. In fact, I believe Sister Cecilia was a bit of a renegade among her peers. We loved her.

Her four-year course started with drawing with charcoal, usually a plaster bust of some sort. After that, tempera paint, then oil and finally watercolor. We received individual attention for four years, which was a priceless gift, and I feel that it was the best foundation any budding artist could have had.

Her mantra was something like, “You can break the rules after you had mastered them”… which meant, we had to have a solid foundation in color theory, design and composition before we could fly on our own. She would always tell us, “talent is 10 percent of success as an artist, practice was the other 90 percent.” While we worked, she would read art history to us and then quiz us on it later.

She was a gift to the school and to all the students who were fortunate to know her. She was a role model in the day when women were just beginning to realize their potential and worth. Sister Cecilia knew us all well and helped us develop a sense of self-worth through hard work and more hard work. She believed in us.

MYSTIFYING MASS

The first time I went to Mass at the Mount — or anywhere — was mystifying. I frantically said to a friend in line in front of me as we assembled in the hall outside the chapel, “I have no idea what to do.” “Sit behind me,” she reassured me and “ do what I do.” I did, and I did.

She reached into a box at the doorway and pulled out two dark blue nylon net squares with little lace borders all around and handed one to me. I put it on my head, just as she had. We filed into the sanctuary along the right side, turned left in front of the organ and walked up the center aisle. Genuflecting before entering the pew was my first surprise. Kneeling benches were new to this Calvinist as was kneeling every whipstitch, which we did immediately. I realized as the service progressed that my timing was off a second or two while I tried to mimic my friend and follow her every move. The year was 1960, before Vatican II, so the Mass was said in Latin with the priest facing away from the congregation.

I have recently converted to Catholicism, and I find the constant movement called for in the order of service meaningful and reassuring. Last winter, I attended the funeral of a Presbyterian. We moved about as much as the dear departed, not even standing for hymns and praying in a seated position. It all seemed wrong somehow.

SACRED SPACES

The music hall was just one of many spectacular rooms in the iconic building complex. On the third floor of the right-hand side of the building, it sported stained-glass windows and crystal chandeliers, a stage with two grand pianos flanking it on either side. The room was large enough to seat the student body, the community of sisters and guests. It saw so much in its long history from recitals to graduation ceremonies and everything in between. The space was almost sacred, and it was not difficult to imagine women in pre-antebellum clothing, in hoop skirts gathering there to watch a graduate recital or choral performance.

Just outside the stage on the roof was a spiral fire escape descending the whole length of the building. On graduation day, the senior class, adorned in white gowns, would go to the fourth-floor dorm and file down the section of fire escape that spanned the two floors. I guess it was our grand entrance onto the stage or something. I don’t know why we couldn’t have filed into the music hall another way. We made it that day without incident. We all had visions of one person near the top tripping and taking out the ones below like dominoes.

On very special occasions, Bishop Hodges would oversee things from a throne-like chair on the stage of the music hall. Graduation was one such time we were graced with his presence. As president of the junior class, I was responsible for delivering a short welcome or something, I forget now what it was. It was gradation 1964 and, as instructed, I climbed the steps and gingerly approached the prelate. After a curtsy type of move, I addressed him as his “highness.” He erupted with his classic laugh simultaneously with the gasps of the Sisters seated in the first row in the audience. The proper word was “excellency,” and, in my nervous mind, I must have thought they were equal. He was known for his kindness and his sense of humor. Thank God.

A HAVEN OF PEACE

The 1960s was a tumultuous, exciting decade in this country’s history. Lots of things took place — good, bad and worse. As students in a nearly cloistered environment, we were blessed to have had that haven of peace and grace we took for granted. In retrospect, the dedicated sisters, the bucolic campus and the time-honored traditions were priceless comforts in a time full of change.

The years between then and now have taught most of us how precious that wonderful place was. Tragically, the building is no longer, but as long as the last alumna lives, we will recall the first line of the song we all sang — “High upon a slope majestic.”

• Anne Hazlett Foreman, an award-winning artist, has been a member of Artworks Around Town for 20 years, having been on the board for the first four years. She also has served as chairman of the Oglebay Institute Mansion Museum Committee; served two terms and was vice president of the West Virginia Independence Hall Foundation; served on the Oglebay Institute Board of Directors, the board of Fort Henry Days and the Wheeling Hall of Fame board; and is a member of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. Foreman is a graduate of Mount de Chantal Visitation Academy and attended Wheeling College and Chatham College. She is married to Robert Noel Foreman, and they have six children and several grandchildren.