Nights can be noisy in the summer. From wild critters moving about to folks staying out late to take advantage of the nice weather, there are a lot of things that go bump in the night. In the days that lead up to the Fourth of July, these nighttime noises often include explosions. While the most recent firework-regulating ordinance was passed in 1981, you may be surprised to learn that efforts to reduce harm around fireworks aren’t new. Ordinances, laws, and proclamations discouraging firework use in the city have been around since the early 1900s. With all of the improvements to safety over the years, it’s easy to forget just how dangerous explosives can be, and how widespread firework-related injuries were.

A Brief History of Fireworks

Over 2000 years ago, someone in Liuyang, China, threw some bamboo into a fire. Because bamboo stalks have air pockets in them, they overheated and exploded – creating the first firework! This phenomenon was improved upon in the first millennium when Chinese alchemists mixed potassium nitrate, sulfur, and charcoal to produce the first “gunpowder” which was then poured into bamboo sticks. After additional improvements and widespread adoption by European rulers, shooting off fireworks became a customary practice for holidays and celebrations.1

Of course, early colonists brought their love of fireworks with them across the ocean to what would become the United States. A letter from John Adams to his wife, Abigail, expressed his vision for how the holiday should be remembered:

“[the Fourth of July] ought be solemnized with Pomp and Parade with [shows], Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires, and Illuminations from one End of the Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” 2

Games, bonfires, and illuminations? That’s not far off from many of today’s celebrations. In Adam’s time, fireworks were still colorless explosions. It was in the 1830s that Italians are credited with a further firework innovation, adding metals to achieve the colored explosions that we are familiar with today. 3

Exploding Cannons and Other Mishaps

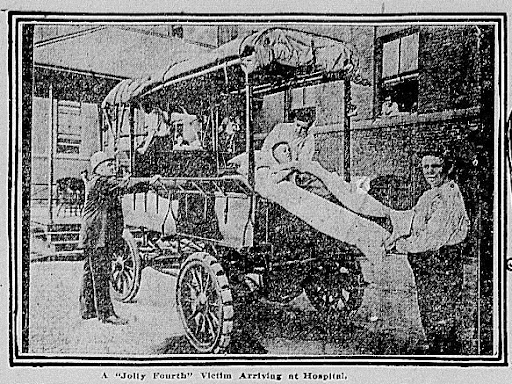

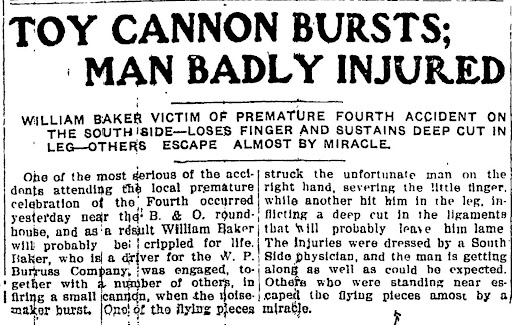

Fireworks are supposed to evoke feelings of joy, pride, and wonder, but they can also leave a trail of injury and death in their wake. Historic users of fireworks were often blinded, had limbs or digits blown off, or even died from mishaps. Tetanus from shrapnel was also a common cause of fatalities. Fires resulting from fireworks could, and did burn entire towns. This was especially serious as firefighting equipment of the era was not as effective as what is available today.

The American Medical Association began tracking July Fourth related injuries and deaths, and within the decade it became obvious there was a serious problem. With more than 1,500 deaths and 33,000 reported injuries by 1910, the AMA’s records quantified seven years of holiday-related mishaps. Rather than relying on anecdotal accounts of bad things happening, concrete data could be used to demonstrate how dangerous fireworks could be.

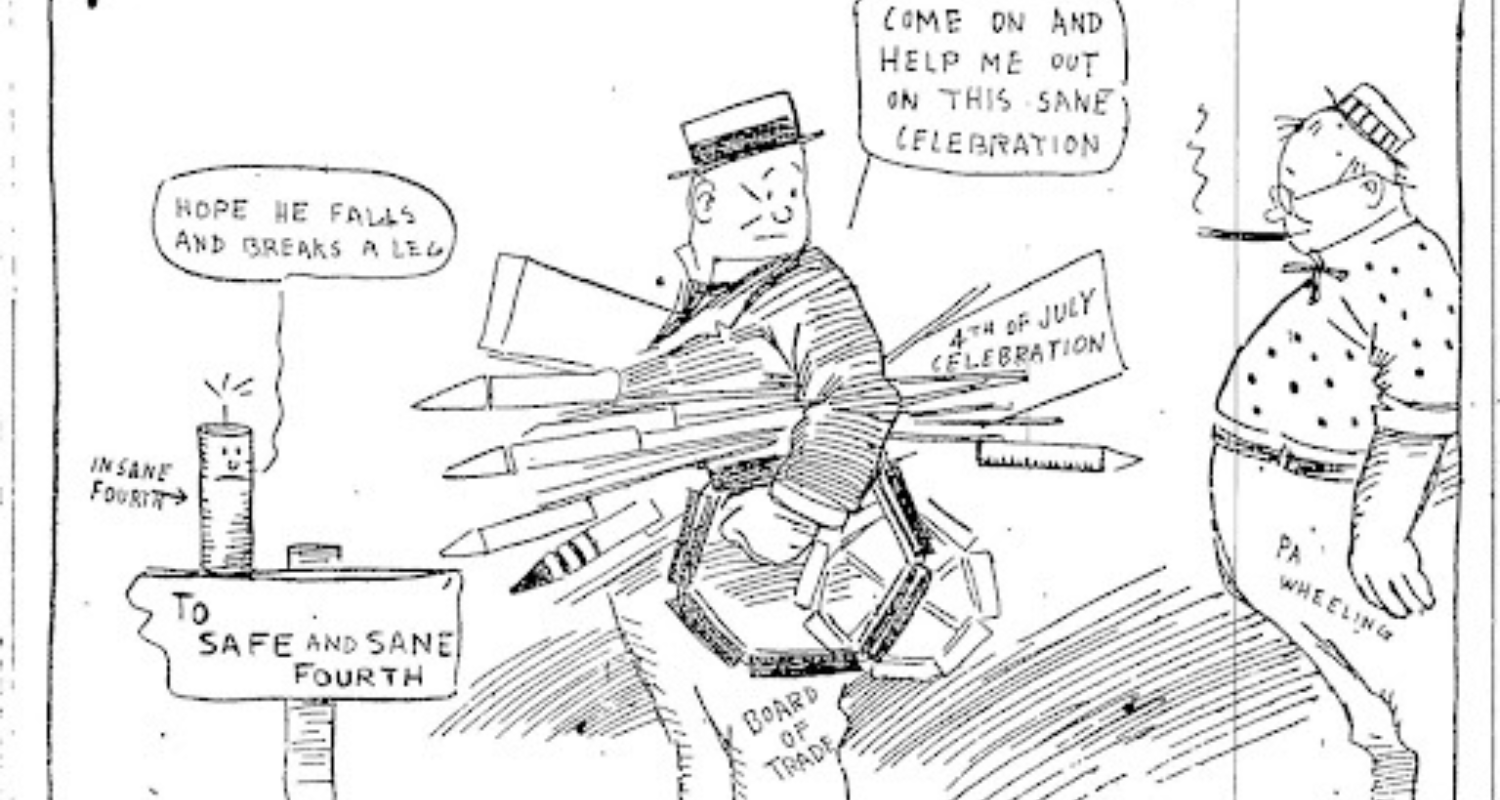

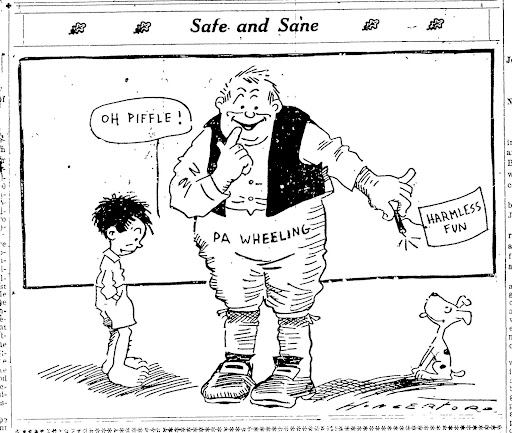

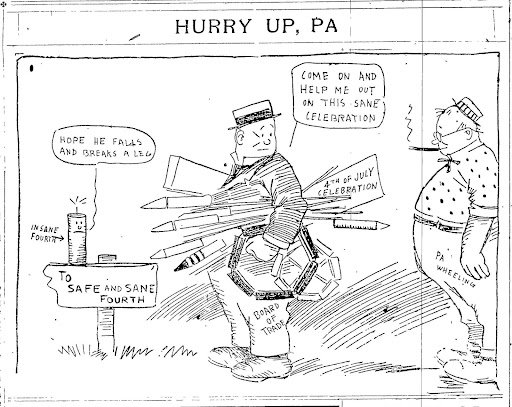

“Safe and Sane” Comes to Wheeling

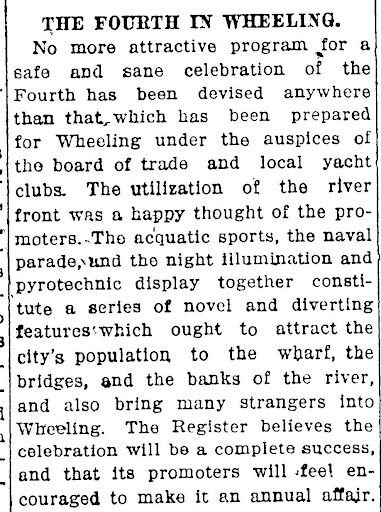

Armed with this knowledge, cities across the country began to roll out “Safe and Sane” Fourth of July initiatives. Cities and civic organizations planned events that featured picnicking, dancing, live music, field games, and parades.5 In Wheeling, celebrants gathered at the waterfront, Wheeling Park, and other community spaces in the city.6 Not to be left out, cities across the river also had their own “safe and sane” holiday schedules as well. 7

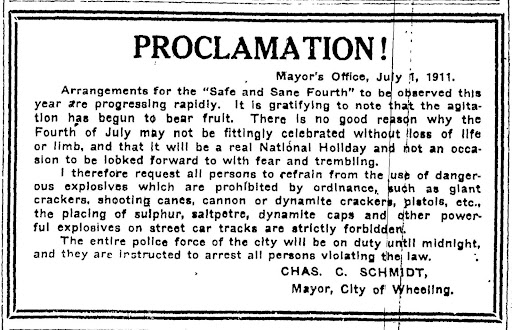

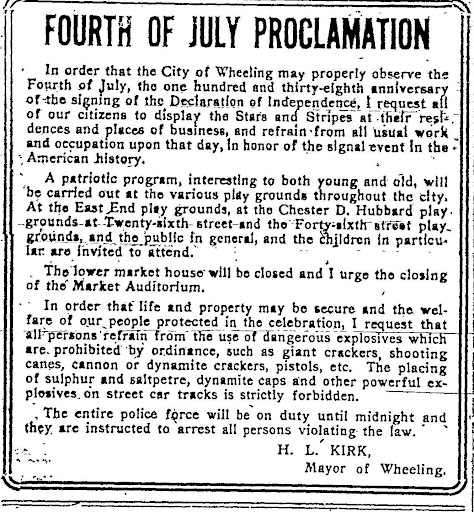

Additionally, Wheeling mayors would include proclamations in the newspapers leading up to the holiday. These proclamations expressed their expectations for the day, and reminded citizens about the ordinances already in place to curtail fireworks discharged in the city.

Local Businesses Join Safety Efforts

Local businesses quickly began incorporating “Safe and Sane” language into their Fourth of July advertisements. Whether this was a demonstration of their investment in community health, or just a chance to capitalize on some hot buzzwords, we may never know. A survey of advertisements during this era shows common incorporation of safety-oriented language in their advertisements. Those that didn’t include mention of “Safe and Sane” just simply stated they would be closed and wished shoppers a happy holiday. Meanwhile, Bayha Bakery continued to use imagery and language that promoted firework use. At face value, it could look like they were making a subtle commentary on the fireworks ban, but it’s also possible that they were just recycling old advertisements.

The Future is Safe (and Sane)

Beyond the “safe and sane” campaign, other conditions put a damper on raucous displays on the Fourth. Prohibition came early to West Virginia, with the Yost Law going into effect in 1913.8 Local papers announced on July 1st that “West Virginia is now on the Water Wagon.”9 We know now that temperance movements only bred underground alcohol economies, but regardless the law shuttered Wheeling breweries and beer gardens.

Defense manufacturing also took a bite out of July fireworks, with fireworks and ammunition sharing many of the same ingredients. A science publication related in 1941 predicted that the wartime demand for magnesium and aluminum would hamstring the commercial firework industry for the subsequent year.10 Even if materials became available after the war, many states began to limit large firework displays to professional settings.11

While some of the language surrounding holiday safety has changed, the desire for an incident-free Fourth has not. Small fireworks like sparklers, fountains, and party poppers are of course permitted within the city limits, but if you’re looking to see something larger, it’s best to leave that up to the professionals. Luckily, Wheeling and the greater Ohio Valley are home to several large fireworks displays to celebrate the Fourth of July. Which did you happen to catch this year?

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.

References

1 Alexis Stempien, “the Evolution of Fireworks” Smithsonian Science Education Center: STEMvisions Blog. https://ssec.si.edu/stemvisions-blog/evolution-fireworks

2 Sarah Pruitt, “Why Do We Celebrate July 4 With Fireworks?” June 29, 2022. History Channel. https://www.history.com/news/july-4-fireworks-independence-day-john-adams

3 Alexis Stempien, “the Evolution of Fireworks” Smithsonian Science Education Center: STEMvisions Blog. https://ssec.si.edu/stemvisions-blog/evolution-fireworks

4 “Fire Destroys Western Towns.” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 5, 1911

5 Michael Waters “The 1900s Movement to Make the Fourth of July Boring (but Safe)” Smithsonian Magazine. July 2, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/1900s-reform-movement-made-fourth-july-safe-and-sane-180972537/

6 Wheeling Intelligencer, July 3, 1910

7 “Shadyside and Bellaire Safe and Sane Fourth of July Celebration.” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 2, 1910

8 Jane Metters LaBarbara, “New Research on Prohibition in West Virginia.” September 9, 2013. https://news.lib.wvu.edu/2013/09/09/new-research-on-prohibition-in-west-virginia/

9 Wheeling Intelligencer, July 1, 1914

10 “Fireworks for Defense Aids Safe and Sane Fourth.” The Science News-Letter Vol. 39, No, 26 (Jun. 28, 1941) https://www.jstor.org/stable/3917972

11 “Brooks Blevins, “Fireworking Down South” Southern Cultures, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring 2004). University of North Carolina Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26390921