Editor’s note: Two memorials are scheduled for Tom Stobart. The first is at 7 p.m. Sunday, Aug. 30, via Towngate Theatre’s Facebook page. The second will be an in-person event at 3 p.m. Saturday, Sept. 5, at Towngate Theatre. Seating will be limited.

“Discover in all things that which shines and is beyond corruption.”

— William Saroyan

Every town of a particular size is entitled to a certain number of eccentrics, characters and hidden geniuses. On Aug. 4, Wheeling lost at least two of its most prominent: Tom Stobart the proprietor of the Paradox Bookstore, and Tom Stobart the playwright and thespian.

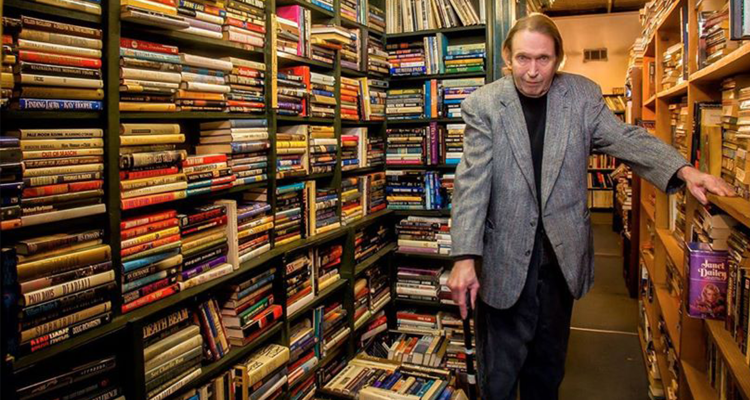

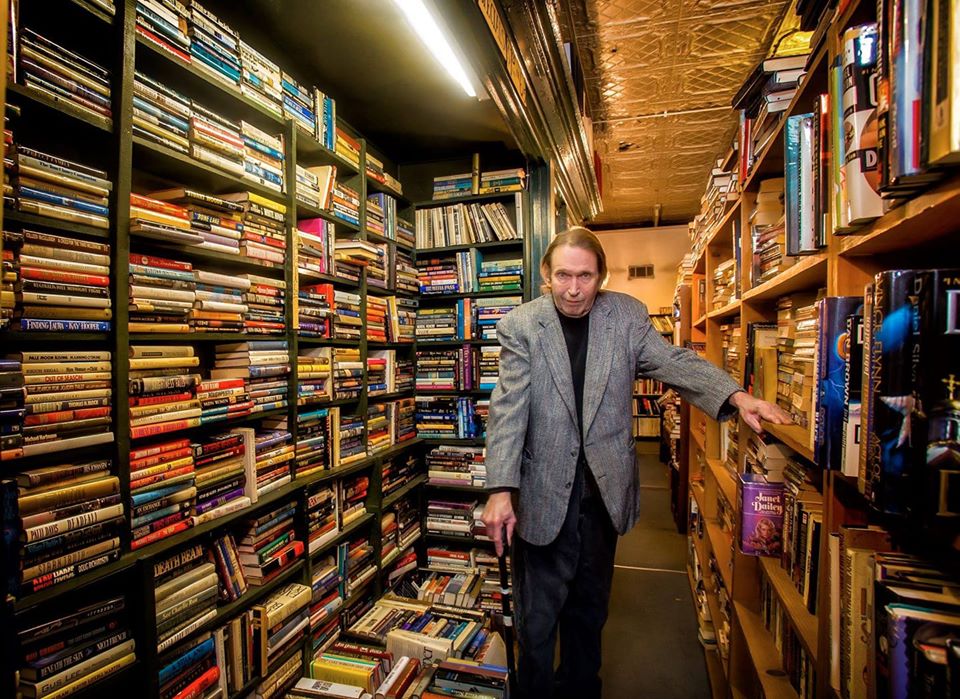

Stobart was known to national and international audiences as the owner of the Paradox Bookstore, with its famous signs adorning the entrance admired by readers worldwide — even at The New Yorker.

But it was as a playwright that Stobart created a lasting legacy. He wrote 17 one-act and six full-length plays, many of which were performed at the Oglebay Institute Towngate Theater, but he also gave license for his work to be performed at other local venues, helping give birth to new projects and new artists. And his plays were performed in Pittsburgh, Columbus, Los Angeles and Japan.

In a series of interviews with friends and collaborators, a picture of the man emerges: one who made an early commitment to the theater and who remained steadfast to that commitment over the ensuing years, despite struggles with finances, health and alcoholism — the disease that, by his own admission, ultimately killed him. Though he never achieved the level of professional fame and success he may have once sought on his two trips to New York as a young man, he made himself one of the leading lights of Wheeling’s artistic community for nearly 40 years. And he remained rooted in the everyday life of the community, setting his plays in its working-class bars, homes and stores.

THE EARLY YEARS

Butch Maxwell, actor, playwright, friend: I actually met Tom first when we were both in Cub Scouts. We were in the same den together. He lived on Vernon Avenue in the Patterson area of Elm Grove. I lived on Paxton Avenue when I first moved to town. And that was where my mother was the den mother. He lived there and went to Kruger Street School.

Howard Monroe, radio host, childhood friend: Ethel Sweeney was our teacher. Neither one of us had a lot of friends. We weren’t particularly outgoing, and we both were a little unusual in our interests. We liked to read and were more introspective and not so much into sports. I think [Sweeney] decided we both were weird enough, we ought to be together, so she kind of decided we were going to be friends. And that’s how we met.

He was very old school, an old soul. And of course with that baritone voice, he would always speak very distinctly. And he would often say to somebody his age or older, “Yes, my good man, how may I help you?”

Maxwell: Tom was an early developer. He was the only kid in the Cub Scout pack who had hairy legs already.

Monroe: His father was a TV repairman. His mother had been a telephone operator back when they were still pulling plugs out of patch bays and patching things in.

Jane Fritz was his teacher. She was a Broadway lover. She loved old music and she took him under her wing and really taught him a lot of this stuff.

Maxwell: When I encountered him a second time, it was in high school. I was a sophomore, he was a junior, and he was working on the yearbook staff. And I went to pick up my yearbook, and paid him. And as I paid him, he turned to me and, in his inimitable baritone, with perfect diction, he said, “Here you go, my good man.” I don’t know what high school juniors, other than Tom Stobart, spoke that way. But a lot of people found it to be affected and perhaps phony, but it wasn’t. Tom was sincere, he spoke just that way.

Monroe: He was made fun of by some, but he was just quirky enough and just eccentric enough to be likable unless he really pissed you off or unless you really took it the wrong way. There was one guy, we called him Lurch from the old Addams Family TV show. Every Tuesday he would beat us both up on our way home from school. It was a Tuesday thing. It was on a schedule. He had some problems with some folks, but not too many.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

Maribeth Thompson, actor, director, friend: He did have some brief escapes as a younger man to New York. He went twice and was hopeful to kind of break into the arts in the city. And for one reason or another, it didn’t work, and he would come back.

Monroe: I don’t think he ever did the usual, “I want to be an actor so I’m going to go to audition,” kind of things. I’m not sure that ever was really what he did. Or if he did, not very much. I think he liked being in New York City. He loved to go to the White Horse Tavern because he was a huge fan of Dylan Thomas’. And that was one of the places he loved. When I went up to visit him for his birthday, that was the one place he wanted to make sure we went to was the White Horse Tavern. I think he just liked to be in the ambiance of writers and culturally important people.

I think he always felt he was going to be an actor until he began to do his playwriting. After he got a couple of plays under his belt, he realized that was a real talent he had. He always wanted to be a successful playwright, but never wanted to do things you had to do to be successful. He was never going to play any kind of a business game. He was never going to write for an audience, he was going to write for himself. He was never going to adapt a script because somebody said it needs to be adapted. He hated when directors would make adjustments to his plays. He just didn’t like that, because ‘it’s my baby, it’s my work, it’s supposed to be the way I wrote it.’

THE THEATER

Maribeth Thompson: It was the ’74, ’75 theater season. I auditioned for a play, and Tom cast me, and that’s how I got started at Towngate.

Tim Thompson, Towngate Theatre: I first met Tom in 1980. It was a summer musical, we were doing “The King and I.” I remember going home and talking to my brother and him saying, “Oh yeah, Sto was the big actor in high school. He’s incredible. He’s brilliant.”

Bob Athey, Cornerstone Project: When we opened the Cornerstone it was kind of a tough first couple of years just because we didn’t know what to do and how to accomplish it. Tom was really the person that got the theater experience going and that was with the one acts. To have somebody like Tom step in and say, ‘I want to do this, and I’ll produce it, and I’ll get all the people together,’ and all we did was take the financial gain from it kind of kept us alive. It kept the Cornerstone doing what it was doing.

Maribeth Thompson: Tom was a great storyteller. No one could tell a story better than he. He just had this remarkable memory for detail, and could embellish, even if it added elements to the actual story that weren’t quite there, were very appropriate and seemed right and made the story even funnier, or more poignant, or more ironic, or whatever. It was always great to listen to him tell a story.

His loves were deep and profound, his love for a particular type of literature, for theater, for art, for music, you always knew where you stood with Sto. He was incapable of not being true to himself. That was just a stunning characteristic, I think. But those things that he loved, he loved without reservation or hesitation, and made no apologies for it.

Athey: If he was in love with somebody, he was in love with them, and he was deeply in love with them.

Valery Staskey, actor, former girlfriend: I probably met [Tom] in the ’80s in the bookstore, but we didn’t become friends until we did “Oliver” for Oglebay in the summer of 1988.

I left for grad school in ’88, and Tom was sort of paying attention to me romantically. I came back from grad school in ’91, and I sort of picked up where it left off. I was like, “This person was interested in me. I’ll go see if this person is still interested in me.”

And he was. So we dated for about three years.

Cheryl Violette, actor, director, ex-wife: I met Tom in the mid to late ‘90s, because we married in ‘97. Through the theater, that’s how we met. And we actually became best friends. We were best friends for a while before we started dating. Our marriage did not work, but our friendship did.

Tim Thompson: He used to call himself “Old Sto” when we were in our 20s because he always seemed older than everybody.

Maribeth Thompson: His nickname was “Old Sto.” He was Old Sto at 23. Everybody was out buying Janis Joplin albums and he’s out buying Ethel Merman albums. That was Sto.

Violette: He was one of the most romantic men I ever met. He gave me a little book called, “How They Met,” and it talks about famous couples and how they met. He inscribed this in the front of the book: “They met at Bud’s bar? Towngate theater in 95? 94?” And then he put in parenthesis, “Where did I meet Ed? And when did I meet him?” That quote was from a play that we had done at the Cornerstone called the “Three Viewings.” It says, “Cheryl Violette was a burgeoning actress and a single mom with an enormous heart. Tom Stobart was a troubled local celebrity with a deep need for a sympathetic ear. They wanted to be best friends and confidants forever. And they will be. A sweet, silly little book for my best friend from her SOS. Silly Old Sto. April 19, 1997.”

Maxwell: [Tom] would do anything for you; anything he was capable of doing for you, he generally was willing to. He was a great friend. On the other hand, if you ever crossed Tom in a way that he felt betrayed, he would write you off forever, never talk to you again. And he would stand by it, too. I never got on that side of Tom, but I saw it happen a lot. He was a human being and full of contradictions.

Staskey: The things I really admired about him was his passion for the theater and for pretty much everything else. He was a very passionate person when it came to the theater, of course, and writing. He was, for many years, he was really the epicenter of the theater community in Wheeling.

In that position, I felt like he had a great deal of power. If Tom thought it was wonderful, he could easily and convincingly get everybody on board with why it was wonderful. The way he would describe it convinced you that it was wonderful. If he hated something, then that was the kiss of death.

Tim Thompson: If it sucked, Tom said it sucked. If it wasn’t working, if it wasn’t up to par, you knew it from Tom. And it was appreciated, because I didn’t like doing things that weren’t up to par and people would snowball me, kind of just say “Oh, that was great. You were fine.” And then later on you hear you weren’t.

Maribeth Thompson: I think sometimes we all kind of forgot just how brilliant Sto was. Because he was our friend, he was the guy who had the bookstore, he was the guy who went out and fixed you lunch, or fixed your dinner.

Violette: I had children from a previous marriage, and actually, Sto never envisioned himself ever being a father. That was not in his plans. But when he married me, he actually hit the ground running with them because he was just doing all these wonderful things for them. He wanted to pack their lunches, he wanted to illustrate cool, fun things on their lunch bags, with their names, and teach them how to play the piano. And he loved to cook. So, he would cook meals, and he jumped right in there, to the surprise of many people who knew him.

THE BOOKSTORE

Athey: It didn’t matter what time of day, if Tom said let’s go get drunk at the bookstore, we went and got drunk at the bookstore. It’s just the way it was, and that’s it. While I was around him and when we were involved as a group, the quality of life in the Ohio Valley couldn’t have been any better. No doubt about it. Those are the memories that I remember. The other stuff just fades away.

April Childers, Paradox Bookstore: My dad, Wade Hamlin, was one of the founders of Towngate Theatre. And so, Tom remembers my mom being pregnant with me. He was always, always a part of my life, and the bookstore was … I kind of grew up down here.

There was a year when I was little, I think I’d probably be about 4. My dad was a steelworker, and they were on strike. And so my dad got stuck with babysitting the little girl, and his answer to that was to hike me all over downtown. And so every day, we’d hit the theater and go build sets with Hal [O’Leary], and then we’d stop down here at the bookstore, and then he’d hike me home, and I was more than happy to take a nap.

Staskey:The bookstore was just this wonderful place where we would meet in the back. It was always a party, and it was always a good party, too.

Childers: The store always had a warm, cozy feel, and it just kind of, you know, the lighting has a glow to it and it was so cold and it’s bright outside with the white snow, but it was just kind of warm and cozy in here. And books. Never-ending books.

Maxwell: If you were to ask Tom what his legacy is, I think he would have said the Paradox Bookstore. I think it was his plays because as I said before, I think his plays were really wonderful and enduring. He was a good actor, but I think he was a very good playwright.

Childers: When he was writing a lot, you’d come into the store and he’d be in the back, just typing away on the old-fashioned typewriter so you could hear the clickety clickety click; and I was always encouraging him to continue writing more. And last I heard, there may be a partly unfinished play that he was working on when he passed.

THE PLAYS

Staskey: He wrote what he knew. He wrote a couple plays about alcoholism. He wrote about people and relationships. Bud’s Bar, that was the place where the theatrical community hung out. It was right across the way from the bookstore. They were pretty crazy times, and they were fun times too.

Maribeth Thompson: He had every right to have had even greater success than he did. You never know when you’re in the right place at the right time, or have the right agent, or what will happen. But his plays, I think, are beyond good. Beyond good. We worked hard to market his plays. I always thought, “These plays are just as good as anything I’ve seen produced other places.”

Tim Thompson: When you take “Minor Auditions for a Major Role,” “In Terminal Decline,” “A Toy Called God,” “The Proprietor,” “Ever After” and “Under the Bridge to the Stars,” those six plays are as good as any play you’d ever read. Absolutely they are. And I wouldn’t change a word in them.

Staskey: My favorite of his plays is “Under the Bridge to the Stars.” A lot of his plays were very autobiographical, and I think that Under the Bridge was the most autobiographical that he wrote. It is a tragedy, and that’s the trajectory that sadly no one could interrupt in his life.

Maxwell: During the last 10 years of his life, he was not very productive because he was ill; but I kept urging him. He said his excuse for not writing was he didn’t have a typewriter, a really lame excuse.

I was looking around for a typewriter and actually came up with a computer. You know, it was kind of an older computer, but we thought we’d take it over to him and show him how to use it just as a word processor, just so he didn’t have an excuse for not writing.

He took one look at that computer as we stood there on that rainy night, trying to guard it from getting too wet. And he said, “You may come in. But if you bring that infernal pornographic machine into my home, I will chop it up with an ax.”

Maribeth Thompson: He never did embrace technology well. He was very phobic of things electronic. I think they just befuddled him. A lot of those things were expensive, and Tom was always on a rather tight budget. There’s a lot of money to run the bookstore. Tom was happy with his electric typewriter in the back of the bookstore. I think it just resonated with him.

Monroe: His plays will be his legacy, but I think in a lot of people’s minds, it will always be his acting and his work onstage.

THE ROLES

Maribeth Thompson: He was very charming and had this wonderful, wonderful voice. And you could tell right away just by talking with him that he would make a good actor. And as it turned out, I found out that not only was he an actor and a singer, he owned a bookstore, and he was a playwright. And that was just all very believable from just having met him that first time.

Tim Thompson: If Tom wanted to, really deep down wanted to, he would have easily been able to make an acting career in New York City. He could be in movies, TV. His plays could all be made and produced nationwide. He would have been an incredible voiceover artist for cartoons and radio and things like that. He could read three pages of dialogue without a mistake, first take, but he didn’t want to.

Athey: He loved playing Fagin, he loved that character, he had played it at Towngate. I think they had done it maybe at [Wheeling] Park at one point, and he just loved that character.

I think he had checked himself into rehab when we were getting ready to do the show, and I was certainly disappointed that I’m going to have to find someone else to play Fagin because he was the perfect character for that. We were auditioning at the Y and getting ready to do the show, and I turn around and look and there’s Stobart standing in the hallway. I’m like, “What’s going on with this?” and he came in, and we had a quick conversation and he said, “I checked myself out, I checked myself out, I had to come audition.”

So he came in, and he auditioned and, of course with his booming voice and everything, he was just perfect for Fagin. And Andrea [Peck] loved costuming him and everything, and it was so funny because he had done the character before, but I don’t think they really made him dance much. And I had done a set that all these ramps going up and down, and I made him, certainly for “Pick a Pocket” number and probably a couple others I made him dance around.

I made him spin, because the coat that he wore was just so wonderful, it would balloon out. Tom would say “I don’t dance Bob, I don’t dance.” He would say, “You just have them dance, you just have them dance.” And I’m like, “No, Tom, you’re in this number. You just need to skip around and jump around,” and he did.

Tim Thompson: He loved Wheeling, he loved Towngate, he loved the Paradox Bookstore. He had all of that right here. He could live around the corner of the bookstore, which was right down the street from Towngate. Bud’s Club was nearby. He had all of his friends right here. He had Hal O’Leary who produced these plays who was a genius and amazing, too. It was all right here for him. Why go anywhere else? And then, you go out into the world, and they want to change your plays, or they want you to do something different, or they try to form you in a different way. He liked it here.

Maribeth Thompson: One of the plays that we did was a play by Tennessee Williams called “The Night of the Iguana,” I want to say that was like in ’76, I’m not sure. We took it to Charleston to perform in a theater competition there and won, and then were able to go to Atlanta, Georgia, to perform in the regionals, and Towngate has a history of having competed in this particular theatrical competition and winning, and then going on to regionals and doing well, there, too, but that was one of the times Tom and I got to travel with the theater to represent West Virginia on the stage. And those were pretty heady times.

Athey: Of all the things I’ve done with Tom, of all the images I have of Tom, the very first one that comes to mind, and there’s video to prove it, was when we did a comedy show at the Cornerstone. Tom played this character of a narrator, and he wore a smoking robe, and he maybe even had a pipe in his hand — I don’t remember. He would come out and talk in Tom voice, and he would do the opening.

He would come out and say, “The Company B characters need to inform you if you’re easily offended, you will be offended. If you’re not easily offended, you will be offended. So if you want your money back, now is the time.” And he would gesture to the door. “Go get it, you can leave.”

He would do this whole opening bit and then he would turn around and the back of the robe was cut out, and he had these fake buttocks sewn into the costume. He would turn around and his ass was showing, and then he walked off. It was a very Monty Python thing of him to do. That’s the image I have in my mind of Tom. Of all the different things that we’ve done together, all the times we’ve been on stage together or directed him, the very first image that pops in my mind is Tom with his ass hanging out. And I said to Butch [Maxwell], “I think he would be OK with that.”

THE END

Childers: About three and a half years ago, I came down just to say hi to Tom, and he made it clear that it [the bookstore] was just more than he could handle anymore. His health was just getting worse, and he wasn’t able to keep it open as much as he wanted. And I’m a writer and an editor, and I work from home. So I was, like, “Well, I can help you with that because I can do my job from anywhere.”

Staskey: Alcohol stole everything from him. It stole his friends. He loved to be surrounded by people. He was terribly gregarious, and he was at his most comfortable when he had people around him all the time. He’d talk to people in the bookstore. It stole his writing ability. He didn’t write anything for 20 years, not even a one act, not even a 10-minute play, nothing.

Maxwell: I ended up writing his obituary. It was basically by default. He told quite a few people that his obituary was to read, “Thomas Scott Stobart, born this day, died this day of alcoholism.” End of obituary. That’s all he wanted. It was out of respect to Val [Staskey] that I revised the original obituary and added in that somewhat awkward line. But I wanted the reader to know that he wanted it in there.

Staskey: Tom wanted his obituary to merely state his name, his state of birth and death, and that he died of alcoholism. That was all he wanted for his obituary. Butch said, “I heard Tom wrote his obituary.” I’m like, “Yeah, and it’s very short.” So it was an extremely important part of his identity to him, and he was never in denial that he had an alcohol problem.

Maxwell: The last time I saw him was in February in the hospital where he was on a suicide watch because he had answered the intake form honestly, when it said, “Have you ever considered suicide?” And his answer was, “Well, who wouldn’t?” … “Who wouldn’t have at one time or another?”

Monroe: I kept thinking to myself, “I ought to call and check.” I knew he had been moving around from nursing home to nursing home, and I never did.

Violette: I talked to him less than a week before he died. We talked for three hours and he was just such a great storyteller that even if you heard the story more than once, it is still extremely funny and interesting. And, that’s pretty much what we did for those three hours, talked about the people we knew and loved, and lots of fun, different memories.

Staskey: I found out he died around 9 p.m. on Tuesday, Aug. 4. I just went and sat on the bookstore stairs and sobbed for a while, and I took a picture of the bookstore.

Monroe: I cried, but I think I may have been crying for myself for having missed that one opportunity to have a final conversation.

Childers: Everybody’s sad that he’s gone. With the bookstore, he hadn’t really been able to physically do a lot in quite a while. And so, it had become kind of a rare occasion when he made it in. So it hasn’t changed a lot on the business aspect, but, on the personal aspect, everybody who came in knew him and had considered him a friend, because he had been here so long. So we’ve done kind of a memorial in the front window. And people have written down different memories of him. Then we put them up in the window with pictures.

I’ve loved this place forever. And it would break my heart to see it close. I think it would be a loss for the entire city and even the whole state. I’ve really never found anywhere quite like this.

(These interviews have been edited for clarity and condensed in some places).

• Daniel Flatley is a Wheeling native who participated in Towngate Theatre productions while a student at Wheeling Central and performed with Mr. Stobart in a Strand Theatre production of “Our Town” in 2003. A writer and reporter, he lives with his family near Washington, D.C. A former Marine, he enjoys reading, running and cooking.