Many of us have fond childhood memories of enjoying “the funny papers”—silly colorful comics often published in the Sunday morning paper. Whether it was laughing at Garfield’s laziness, chasing the antics of Calvin and Hobbes, or missing the football yet again with Peanuts, children and adults alike continue to appreciate a good Sunday comic.

If you flipped a few pages, you would find a cousin to those light-hearted comic strips—the political cartoon.

According to Britannica, a political cartoon is “a drawing (often including caricature) made for the purpose of conveying editorial commentary on politics, politicians, and current events.”[1] While not exclusively, political cartoons have mostly been published in newspapers and add a visual component to the editorial section, expressing opinions or satire about current events and politics. Check out just a few of the political cartoons that have been published in the Wheeling Intelligencer and the Wheeling Daily Register over the years!

A Long History of Political Satire

While political cartoons continue to be found within the editorial pages of many newspapers, they got their start centuries ago. The roots of political caricature go back to Egypt around 1360 BCE and have also been found in the Roman Empire, Ancient Greece, and Ancient India.[2]

One of the earliest—and still one of the most famous—political cartoons produced in America was the “Join or Die” cartoon published by Benjamin Franklin in 1754. Originally published at the start of the French and Indian War, the cartoon commented on the disjointed nature of the separate colonies and supported the colonies becoming one political entity. “Join or Die” was later used to support the colonies during the American Revolution.[3]

While political cartoons in America started at least as early as the mid-18th century, they reached their peak popularity in the late 19th/early 20th centuries with the innovations of the mass press. Newspapers were faster and cheaper to produce than ever before and improved technologies made it easier to fit illustrations into the printing process.[4] Throughout history, political cartoons have used widely known symbols, figures, and motifs such as the devil, Uncle Sam, and famous politicians.

Using these symbols, one benefit of political cartoons was that you didn’t necessarily have to be able to read to understand and appreciate the meaning behind the cartoon. In 1870, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, approximately 20% of the US population (age 14 or over) was illiterate–meaning they could not read or write in any language.[5] Political cartoons could cater to a wide group of people. Not only did you not necessarily have to be literate, but the visualness and humor also captured the reader’s attention more easily than a dense article.

However, political cartoons were still products of the society and people who created them. According to historian Dr. Rebecca Edwards, political cartoons, at least those of the 19th century, “vividly represent the prejudices of the white, Protestant, middle-class majority,” because that was the group of people who largely controlled most of the newspapers.[6] While some papers provided opposing viewpoints—including those expressed through political cartoons—others also leaned towards the politics they preferred.

While political cartoons express aspects of conversations about current events occurring at the time, they also reveal the way that art, humor, and satire play a role in politics and social issues. In the Wheeling newspapers, cartoonists have confronted seemingly mundane small local issues all the way to events impacting the entire country.

Wheeling and the Political Cartoon

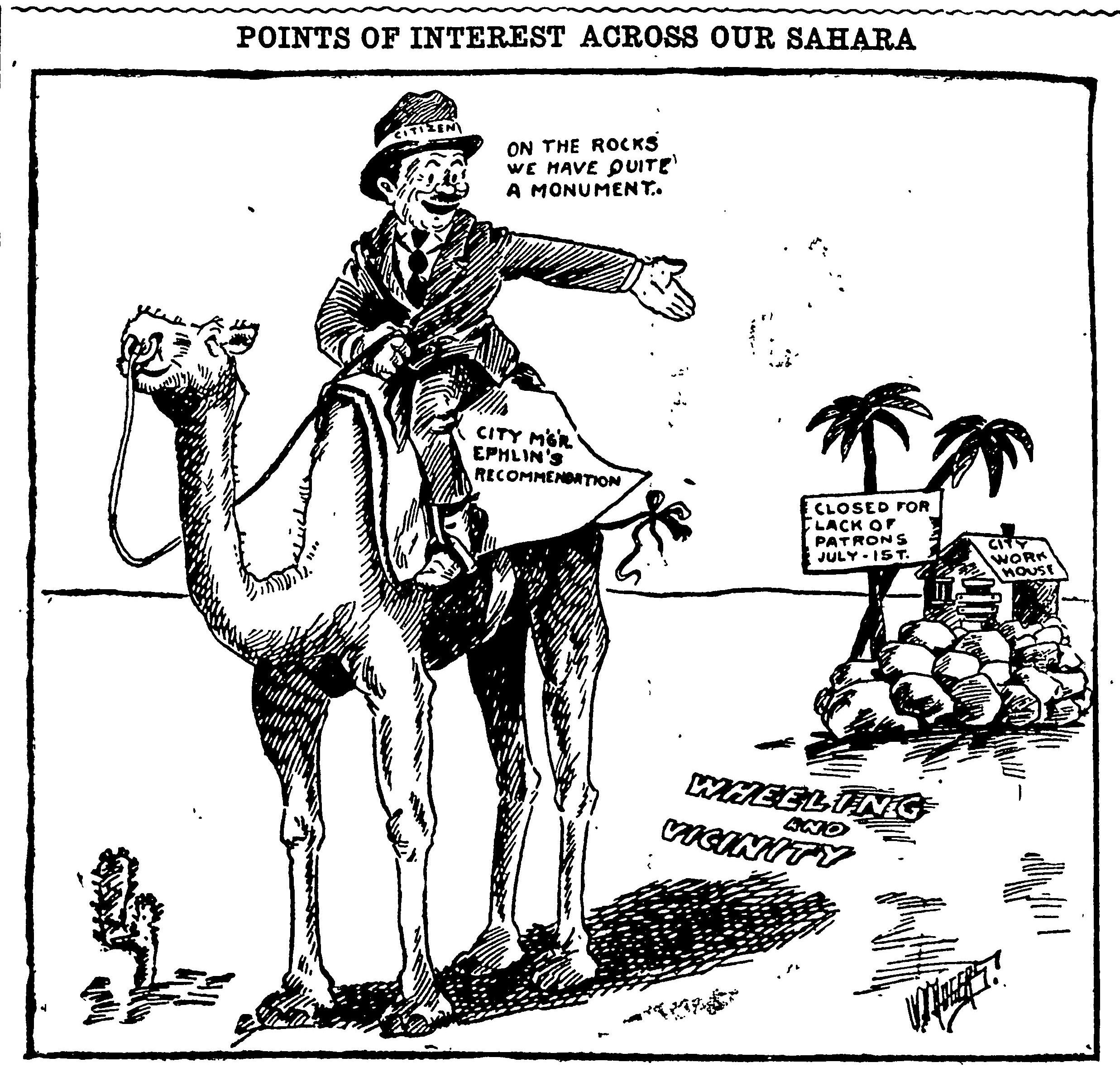

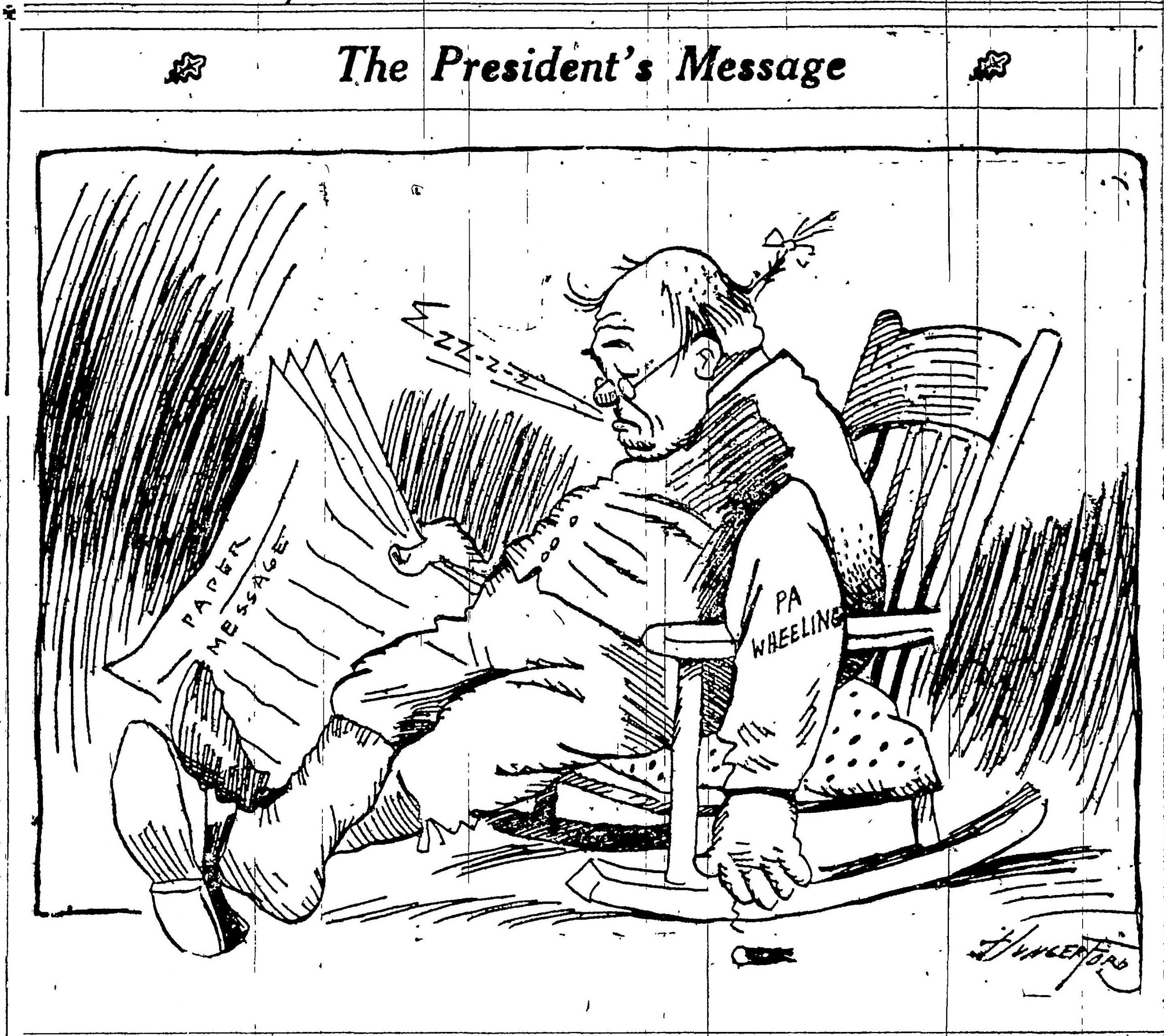

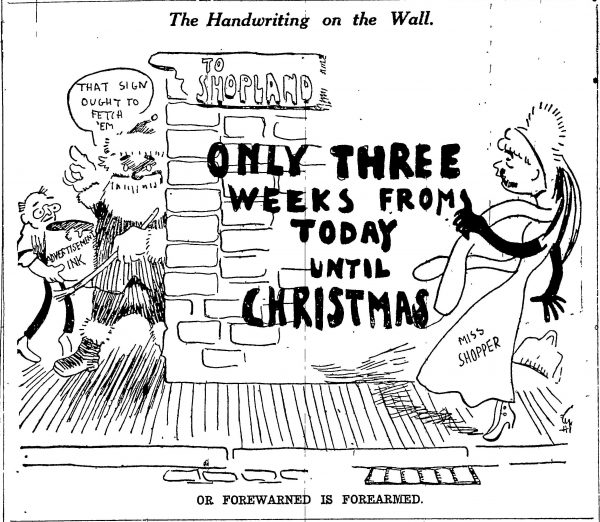

Like many other influential cities of the late 19th/early 20th centuries, Wheeling had plenty of political cartoons in its newspapers. Depending on the specific time and what was happening in the news, the Wheeling Intelligencer and the Wheeling News Register published their own political cartoons or reprinted more national cartoons. Subjects ranged from local societal issues like the Christmas shopping rush to national political debates like presidential campaigns.

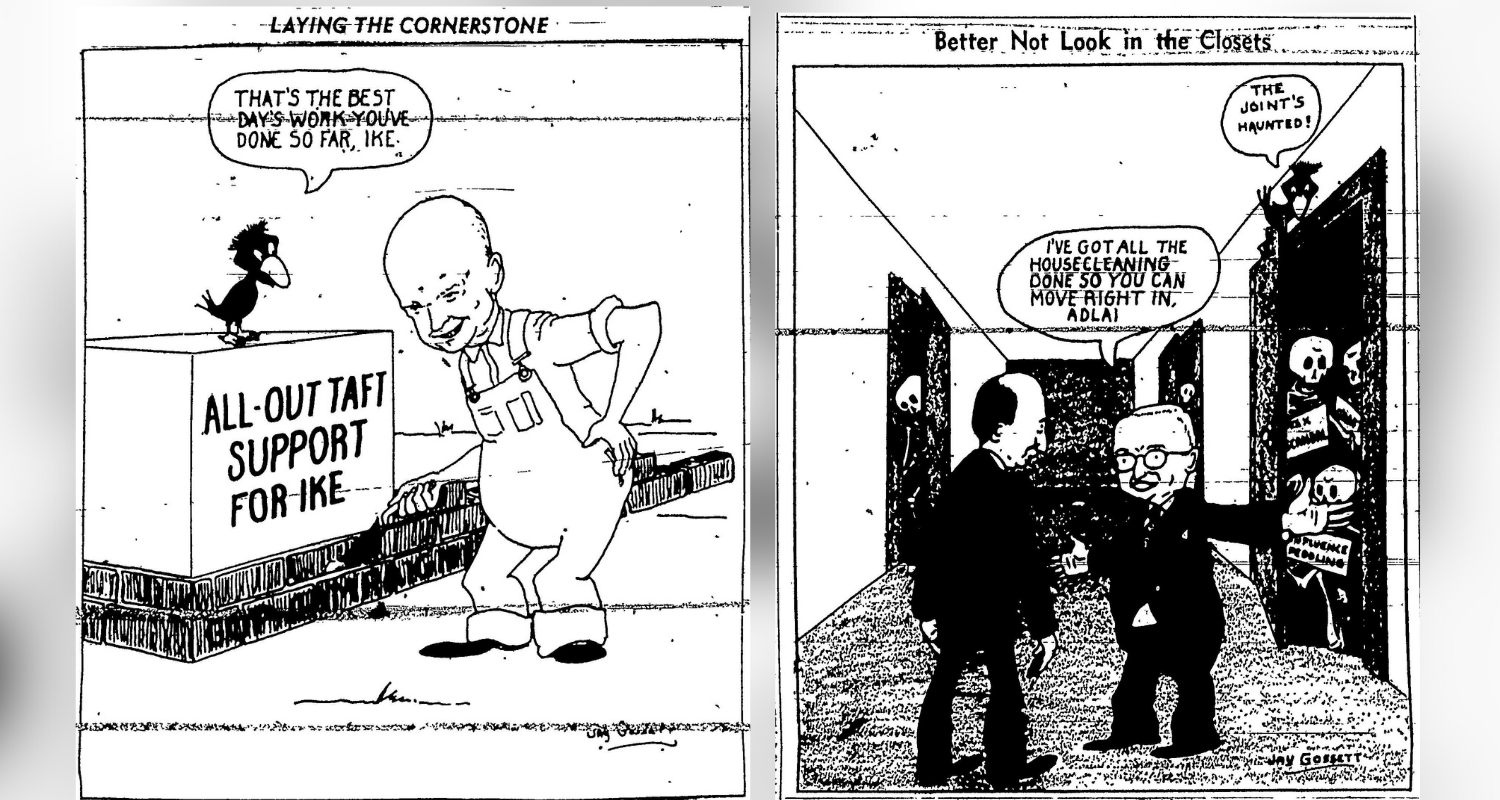

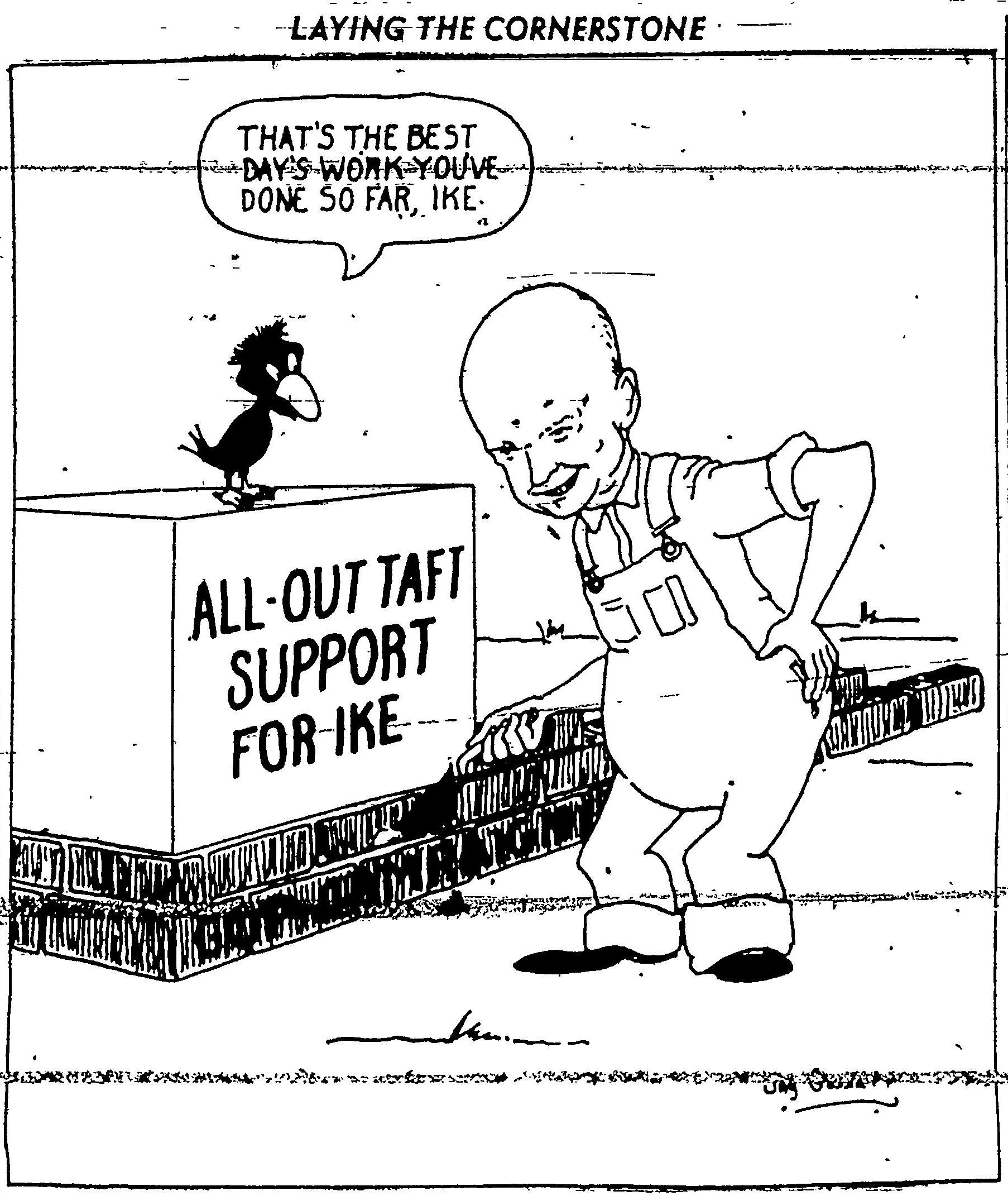

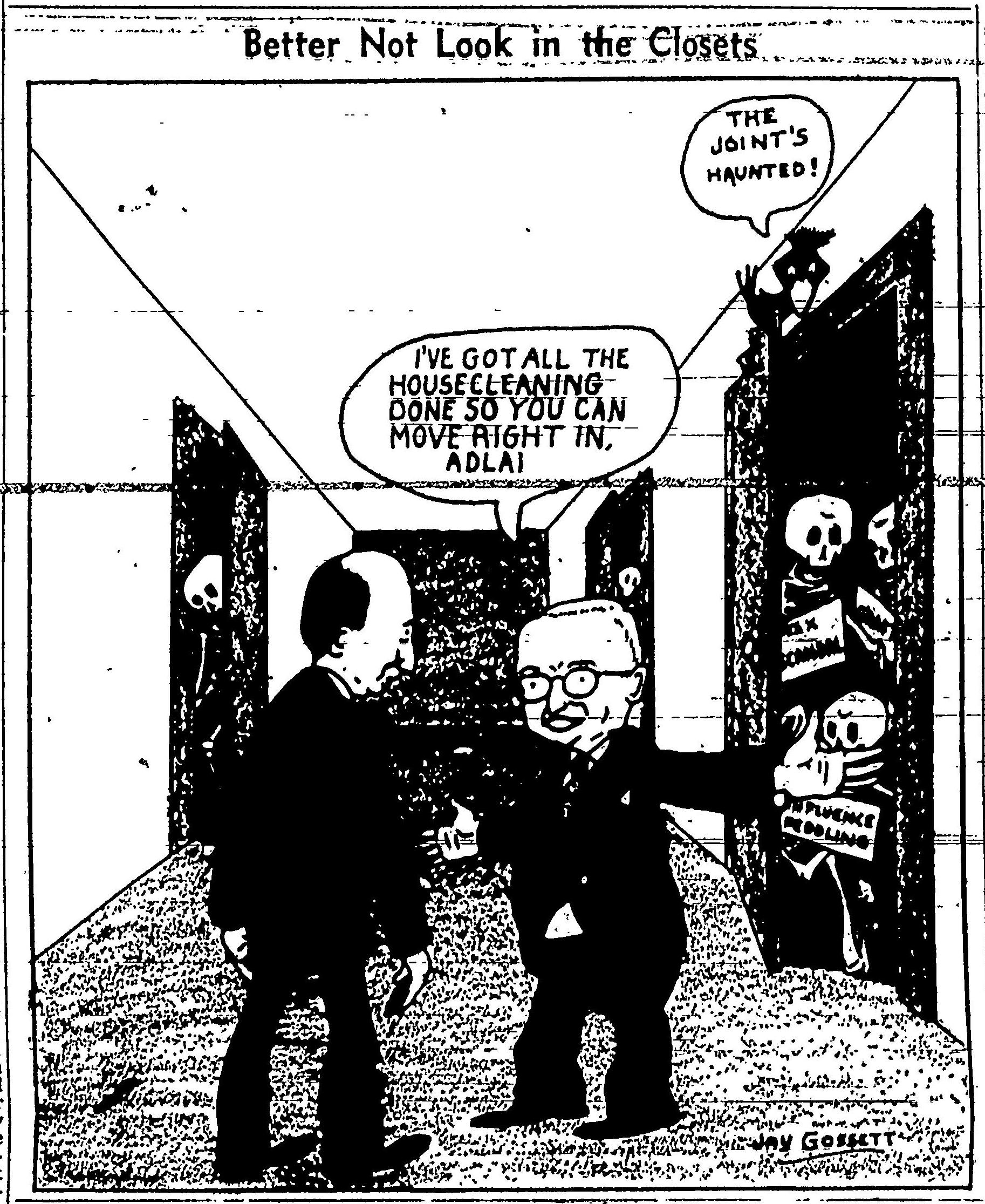

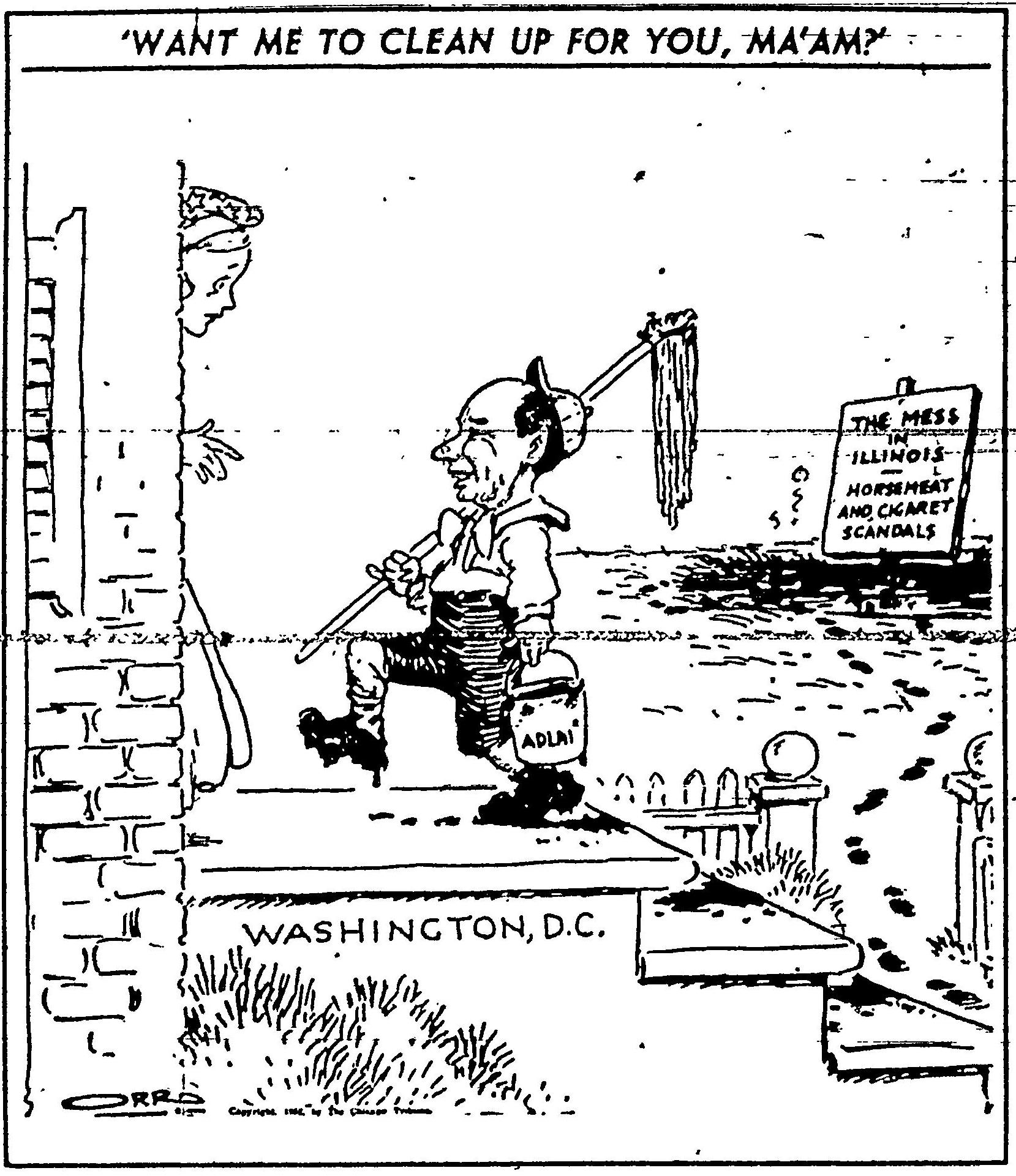

During the early 20th century, political cartoons were often published on the front page of the Intelligencer, immediately grabbing a potential reader. Sometimes multiple cartoons would be included throughout the paper, occasionally offering opposing opinions. For example, on Sept. 15, 1952, the Intelligencer published a cartoon from their newest hire, Jay Gossett, which included a caricature of the Republican candidate for president, Dwight D. Eisenhower. On the same day, they also included another cartoon—most likely created by famous cartoonist, Carey Orr—that poked fun at the other presidential candidate, Democrat Adlai Stevenson II.[7]

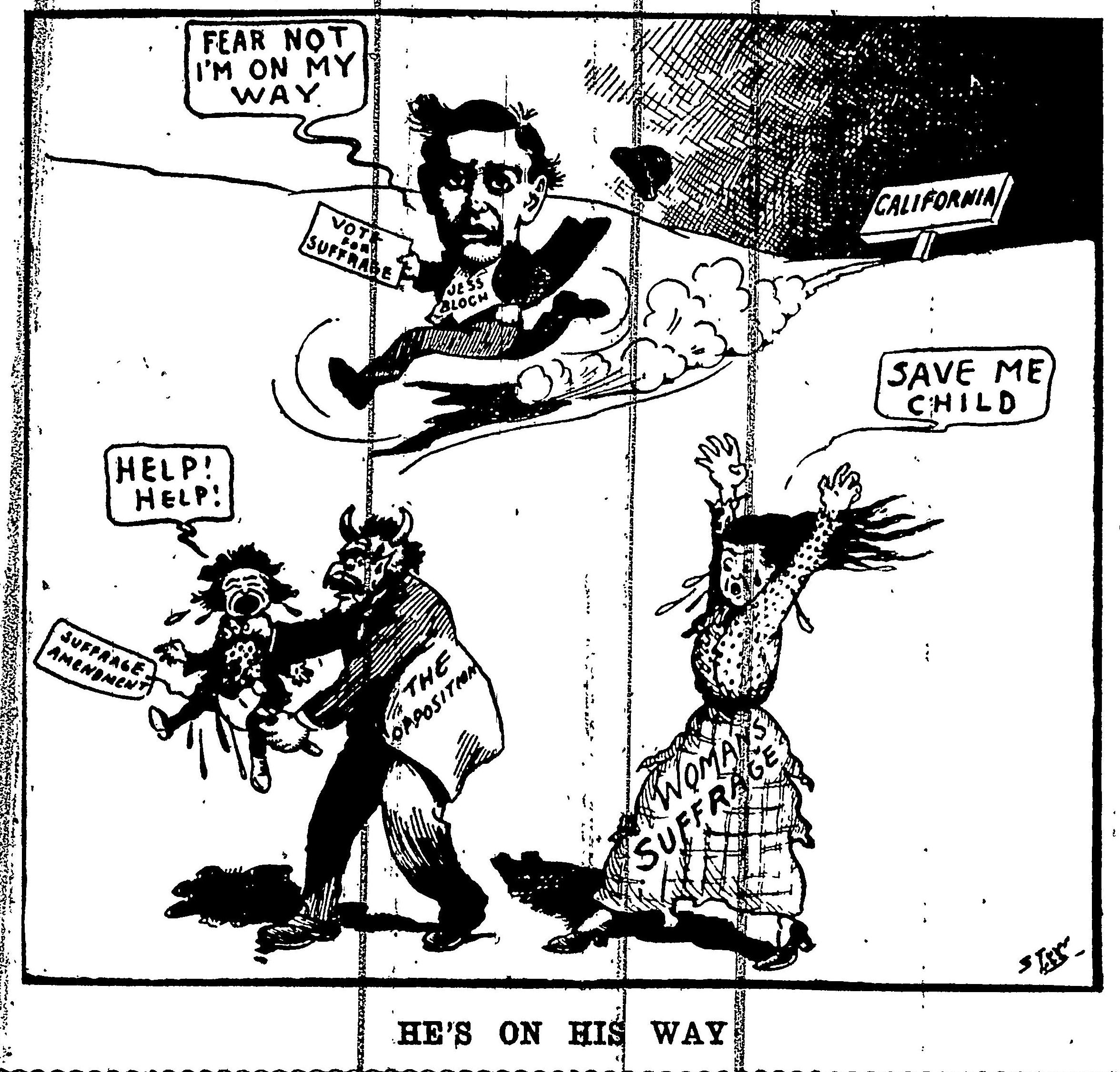

Some of the political cartoons on national topics still had a Wheeling connection. In March 1920, State Senator and Wheeling resident Jesse Bloch (son of Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company president) dramatically raced back to West Virginia from California to break a tied vote concerning the ratification of the 19th Amendment—women’s suffrage. As newspapers across the country documented his travels and location, his home paper, the Wheeling Intelligencer noted Bloch’s contribution to progress.[8]

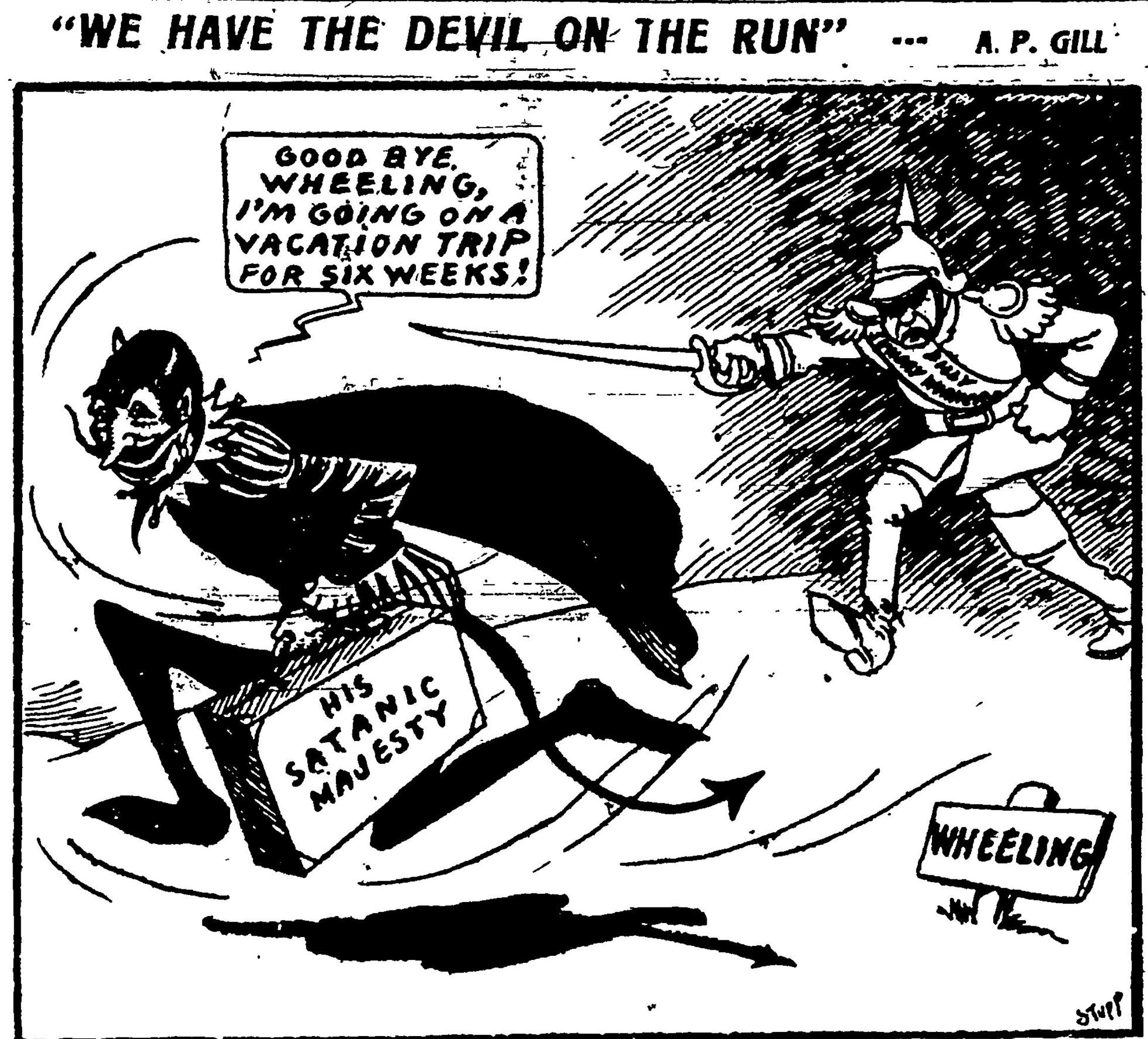

Other political cartoons commented on more local society topics. During the six weeks that the famous evangelist Billy Sunday was hosting his revival in Wheeling in 1912, there were numerous political cartoons depicting the devil being driven out of Wheeling.[9] In another cartoon from around the same time, the cosmopolitan Wheeling teases the visitors from the more rural Canton, Ohio, who they depicted as amazed by Wheeling’s Schmulbach “skyscrapper.”[10]

While many of Wheeling’s political cartoons use motifs recognizable to most people across the country, there were some Wheeling-specific symbols. For example, “Pa Wheeling” was a character representative of the city created by the famous cartoonist Cy Hungerford, who spent a few early years of his career at the Wheeling News Register.[11]

From presidential candidates to state senators racing across the country to the devil in Wheeling, political cartoons have certainly added some visual flavor to the current events of Wheeling, WV.

Political Cartoons into the Present Day

While political cartoons aren’t as prevalent and cannot normally be found on the front page of the Intelligencer anymore, they are still included in many newspapers to this day. Furthermore, with the growth of the internet and social media, there are new avenues and platforms for cartoonists—political and otherwise. In fact, at Weelunk, artist Natalie Kovacs has revived Wheeling-related comics. While Natalie’s comics don’t include political satire, they contain lots of interesting Wheeling illustrations and history—check out her comics here!

Another way that political cartoons remain relevant in the present day is how they have started showing up in educational curriculums. Because political cartoons are created to provide humor and commentary during their specific moment, educators all the way from elementary school to college are using them as primary historical sources.[12] The cartoons help students explore the opinions, viewpoints, and social discussion of issues at particular times using a visual medium.

If you want to explore and find more Wheeling political cartoons, flip through the digitized Wheeling Intelligencer available online thanks to the Ohio County Public Library!

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

[1] Thomas Knieper, “Political cartoon,” Britannica, accessed September 23, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-cartoon.

[2] Ilan Danjoux, “Reconsidering the Decline of the Editorial Cartoon,” PS: Political Science and Politics 40, no. 2 (2007): 245.

[3] “Political Cartoons and Public Debates: Teacher’s Guide,” Library of Congress, accessed September 20, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/political-cartoons-and-public-debates/.

[4] Michael P. McCarthy, “Political Cartoons in the History Classroom,” The History Teacher 11, no. 1 (1977): 29-30.

[5] “Excerpts are taken from Chapter 1 of 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait (edited by Tom Snyder, National Center for Education Statistics, 1993),” National Center for Education Statistics, 1993, accessed September 23, 2021, https://nces.ed.gov/naal/lit_history.asp.

[6] Rebecca Edwards, “Politics as Social History: Political Cartoons in the Gilded Age,” OAH Magazine of History 13, no. 4 (1999): 11.

[7] Wheeling Intelligencer, September 15, 1952, accessed September 23, 2021, p. 1, 4.

[8] Kelly Strautmann, “Radical Ratification: Wheeling’s Role in the 19th Amendment,” Weelunk, March 10, 2020, accessed September 23, 2021, https://weelunk.com/radical-ratification-wheelings-role-in-the-19th-amendment/.

[9] Wheeling Intelligencer, February 16, 1912, accessed September 23, 2021, p. 1.

[10] Wheeling Intelligencer, February 28, 1912, accessed September 23, 2021, p. 9.

[11] Terri Blanchette, “Cy Hungerford Hones His Craft in the Friendly City,” Archiving Wheeling, August 12, 2021, accessed September 24, 2021, http://www.archivingwheeling.org/blog/cy-hungerford-cartooning-pa-wheeling.

[12] Rebecca Edwards, “Politics as Social History: Political Cartoons in the Gilded Age,” OAH Magazine of History 13, no. 4 (1999): 11-15.