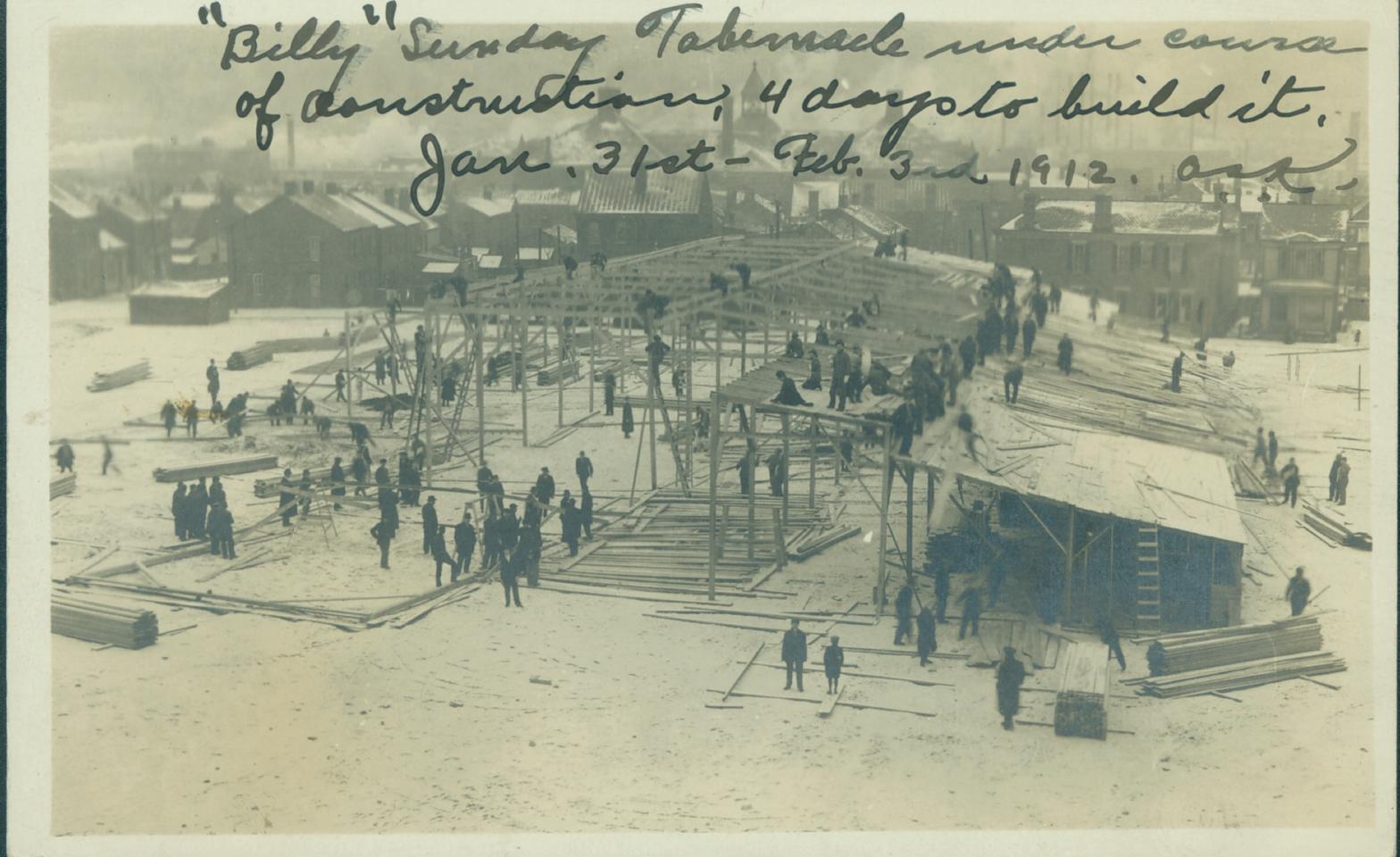

In only four days between January and February of 1912—over a century ago—hundreds of Wheeling residents came together to build an enormous low-roofed building on the eastern side of 26th Street in Center Wheeling. Over six weeks, it would draw tens of thousands of visitors to marvel at the structure and listen to the famous speaker inside—the national evangelist icon, “Billy” Sunday.

Five months later, the giant tabernacle would be gone.

Who was Billy Sunday?

If you were living in the early 1900s, you would’ve had to live under a rock to not know about “Billy” Sunday. He was a phenomenon, a cultural and religious icon, a novelty. Starting out as a professional baseball player for the Chicago White Stockings and later the Pittsburgh Alleghenys and the Philadelphia Phillies, Billy Sunday eventually quit professional sports and became a traveling evangelist preacher.

Originally from a poor family in Iowa, it was during his baseball career on the streets of Chicago that he was introduced to evangelism—the public advocacy of Christian gospel.1 As his baseball career came to a close at the end of the 19th century, Billy Sunday began traveling to preach in small communities across the Midwest. As he became a more popular household name in the early 1900s, he began hosting revivals in larger towns and cities that would be multiple week-long endeavors to revitalize religion in each community and convert attendants to Christianity.2

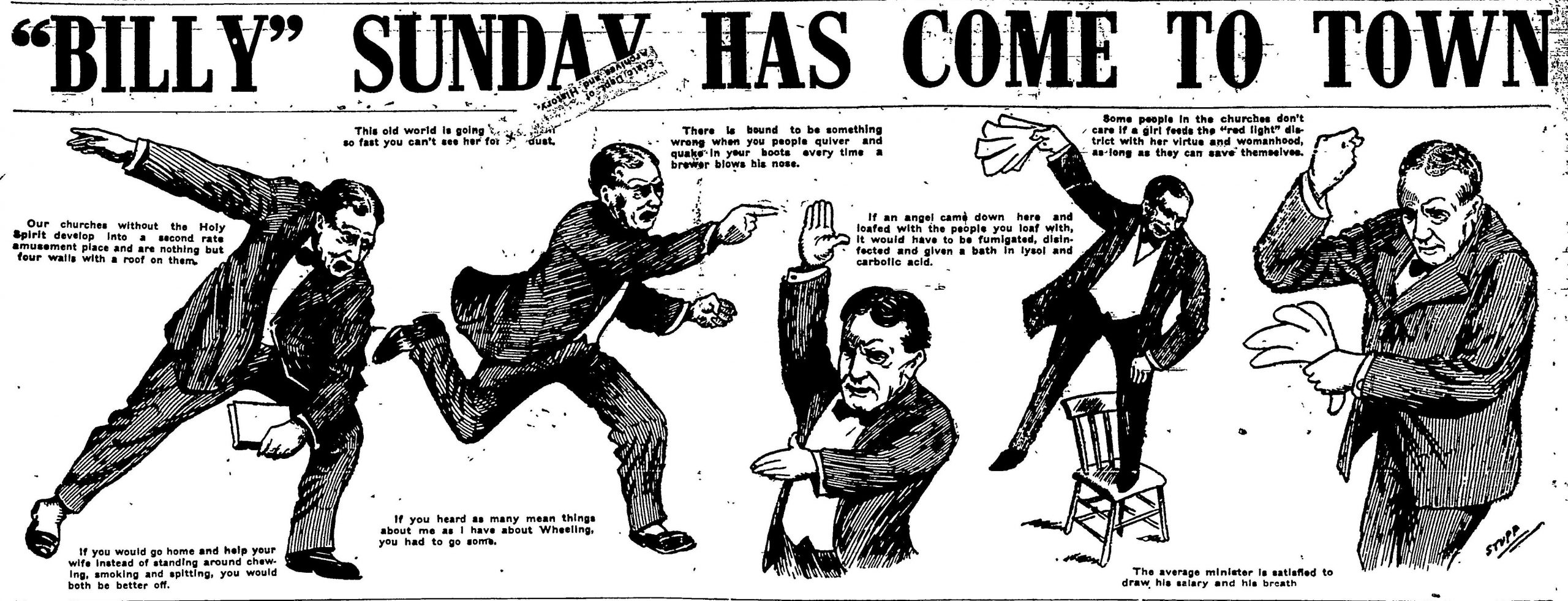

Sunday was known for his theatrical, emotional, and dramatic sermons—it was almost a form of religious entertainment that enthralled entire communities. His sermons, aimed at average folk, varied in topic, but Sunday was best known for his fiery arguments for temperance—the abstinence from alcohol. Billy Sunday would combine his religious and baseball talents as he acted out Biblical stories, adopting “a pugilistic stance as he challenged the Devil and his minions to battle, and mimicked the drama of the diamond by running, jumping, hurling unseen baseballs, and sliding for home plate.”3

In many ways, Billy Sunday was a religious celebrity. In 1914, American Magazine ranked him eighth in its poll on “The Greatest Man in the United States”—tied with Andrew Carnegie.4 In the early 1900s, getting the chance to host a Billy Sunday revival was an honor for a city and entailed weeks of preparation.

The Wheeling Tabernacle

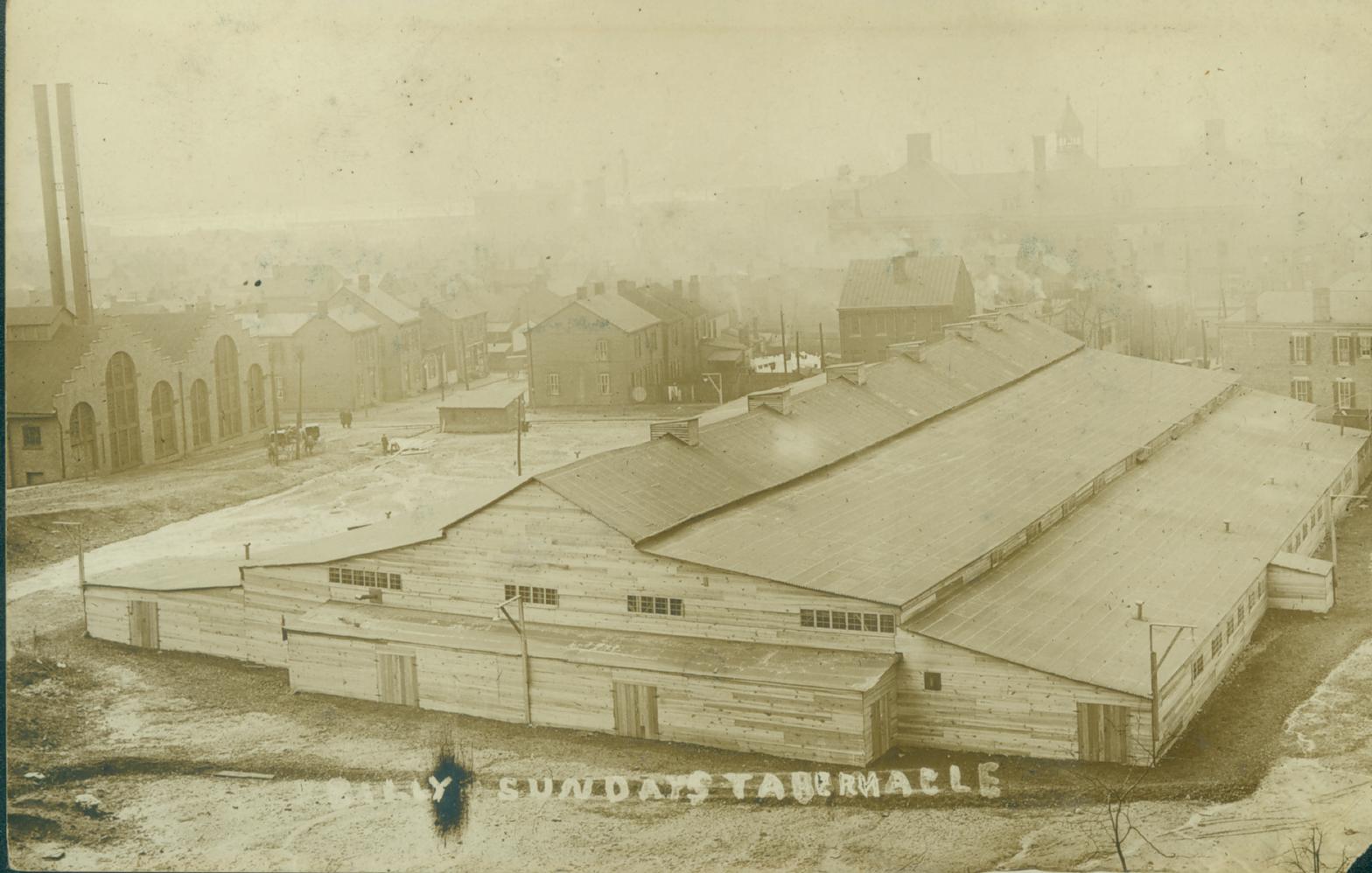

In order to accommodate the thousands of people who flocked to Billy Sunday’s sermons, tabernacles—large one-story simple structures—were built in the cities and towns that hosted Billy Sunday revivals. Wheeling was no exception.

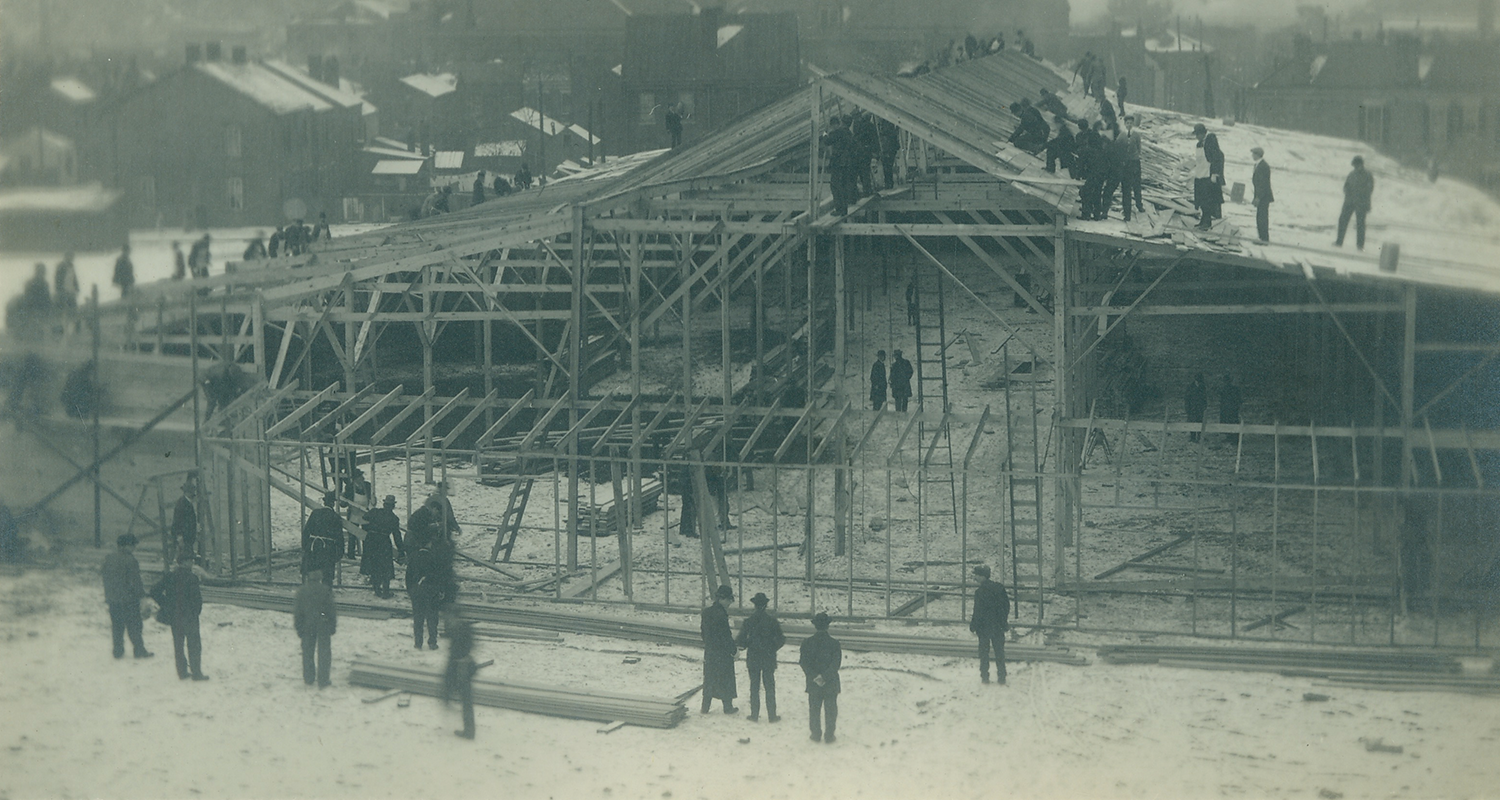

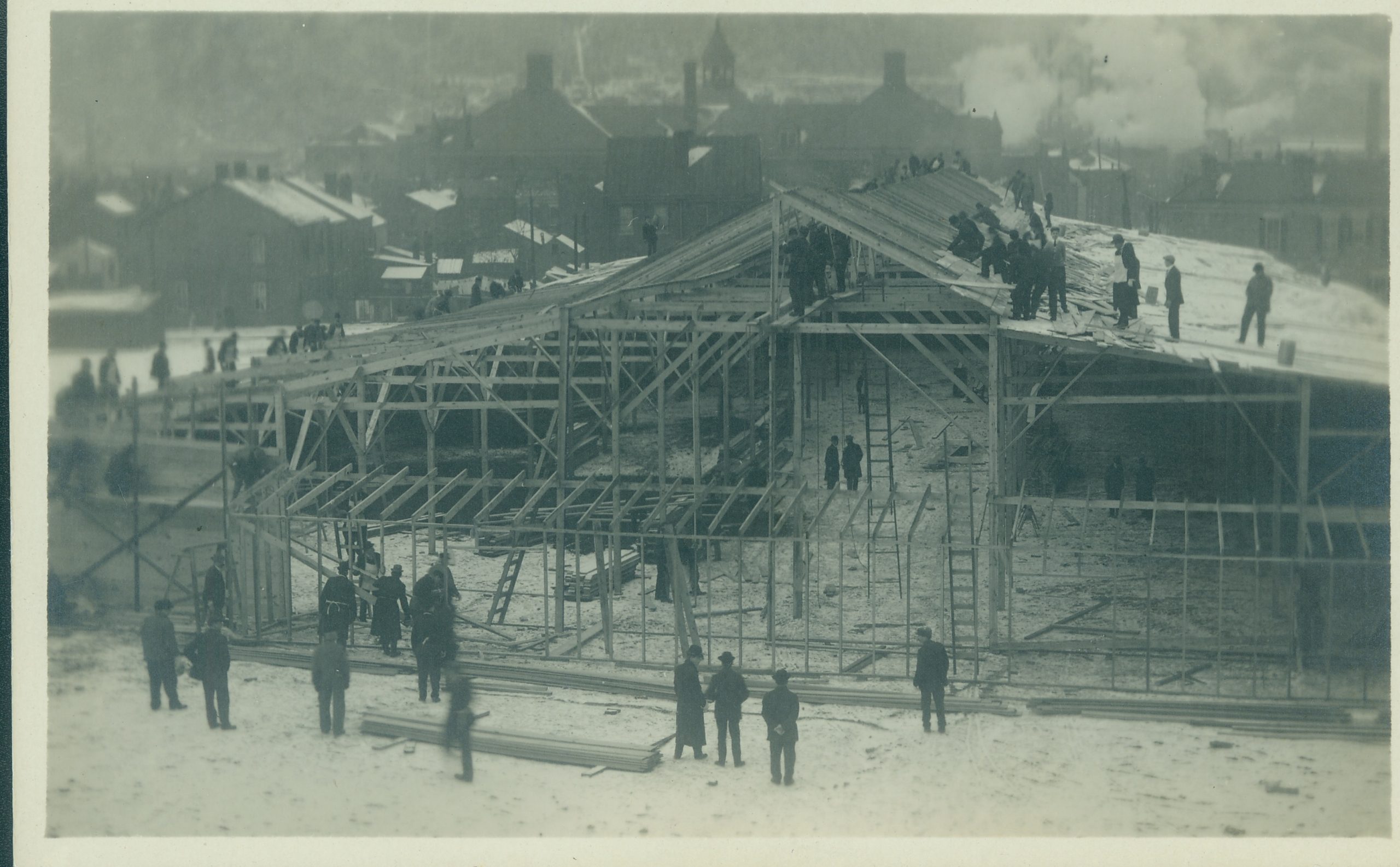

The Wheeling Tabernacle was started and completed in a mere four days—from January 30th to February 2nd.5 Hundreds of Wheeling residents volunteered their time and expertise to build the giant structure in record time. Occupied with long benches, the seating capacity of the Wheeling Tabernacle was around 8,000 people and was heated by fourteen gas stoves. To accommodate the expected large crowds of people traveling daily to the Tabernacle, special streetcar services were set up to and from various other areas of Wheeling and its surrounding suburbs.6 Even only halfway through the revival campaign, the sidewalks leading to the Tabernacle were destroyed from the sheer amount of foot traffic traipsing across every day.7

While men got most of the credit for constructing the Tabernacle, women were not content to be left out. Hundreds of women visited the building site over the four construction days and before long, “a number of the ladies approached the workers and asked to be allowed to drive a nail or saw a board, and in short time it was no uncommon sight to see the ladies bending their energies to the work as well as the men.” Despite their long skirts, some of the women even climbed up onto the roof, but reportedly refused to pose for photographers.8

When the preparations were done, Sunday’s advance man, A.P. Gill, remarked that “Wheeling has broken all records in the great interest shown, the number of volunteers that have responded and the spirit of readiness manifested to do anything there is to be done.”9 One of the final touches to the Tabernacle in preparation for Billy Sunday’s entourage was spreading a layer of sawdust on the ground for insulation. The aisles formed the famous “sawdust trail” that attendants would follow to dedicate themselves to a religious life—“hitting the sawdust trail” became a signature of Billy Sunday’s revivals.10

Wheeling and the “Sawdust Trail”

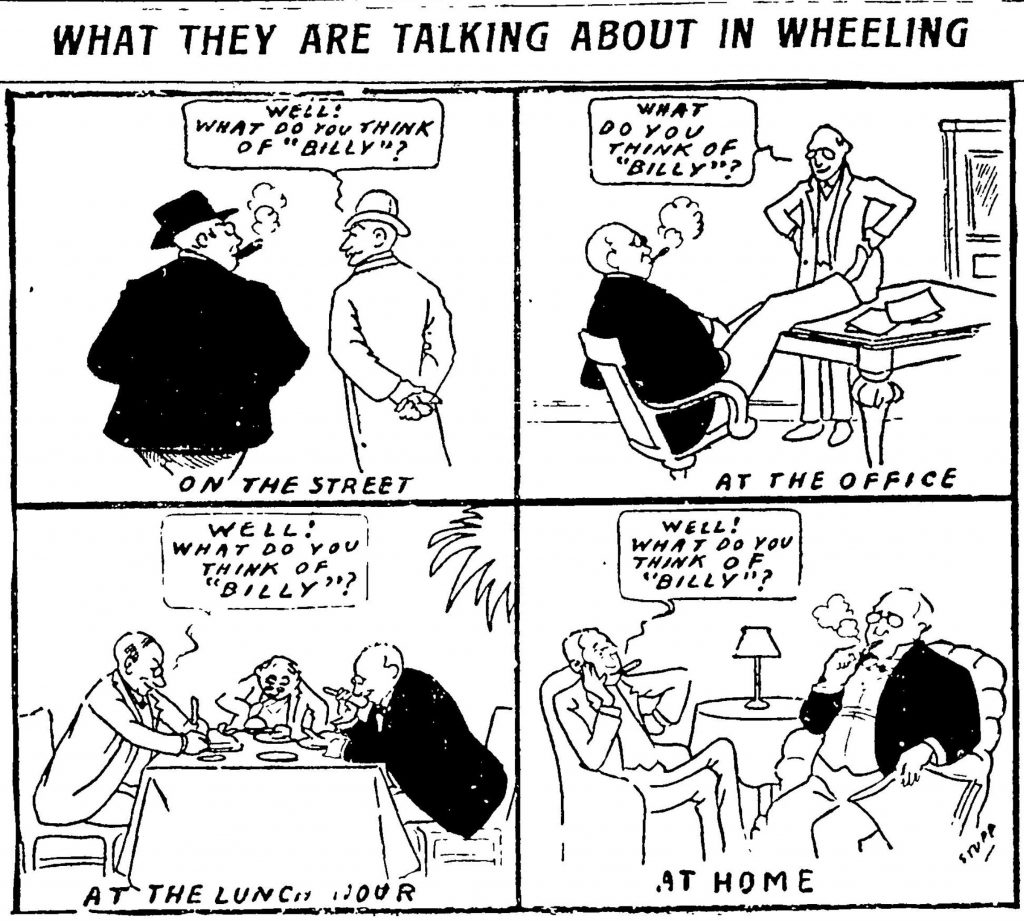

Billy Sunday’s revival was the talk of the town for over two months in Wheeling. Even before the “Baseball Evangelist” arrived, Wheeling residents were preparing by building the tabernacle, organizing dozens of prayer meetings all over the area, and following Billy Sunday’s success in other cities. During the six weeks Sunday was in Wheeling, news, announcements, and gossip of the revival dominated the newspaper—The Intelligencer would reprint his sermons and activities daily.

Almost 25,000 people attended the first day of Billy Sunday’s campaign.11 Based on newspaper coverage, it felt like Sunday reached every Christian in Wheeling. In addition to his regular meetings—held sometimes three times a day—he also hosted special meetings for men and women separately. Even though the tabernacle seated 8,000, the meetings would get so full that people were turned away at the door, for fear that overcrowding would violate fire regulations. Thousands of people traveled from out of town, filling up guest rooms and hotels. For friends and family who couldn’t make the journey, Wheelingites sent them copies of The Intelligencer with all of the exciting details; one person even requested a paper be shipped to a US Army soldier stationed in the Philippines!12

The sheer number of people clamoring for attendance at the Tabernacle often led to drama—all sensationally reported by The Intelligencer, which only added to the novelty of the experience. For example, on March 21st, chaos erupted at the final sermon to women-only when there were so many women trying to get into the Tabernacle that a stampede ensued. In vain, the police officers tried to maintain order, but quickly became overpowered, “caught in an avalanche of coats and millinery.” According to The Intelligencer, one officer had his finger bitten to the bone, while another was “viciously hatpinned.”13

Even outside of his scheduled meetings throughout the week, there were other activities and festivities associated with Billy Sunday in Wheeling. During his stay, Sunday and his associates stayed at the McLure Hotel and during their free time would sightsee around Wheeling and often visit local factories and the churches of surrounding towns. In mid-March, 7,000 local Sunday School students hosted a parade through the streets of Wheeling in honor of Billy Sunday. The children who were too small to walk were carried along in a large freight automobile and Sunday himself joined in the parade.14 However, not all of his commitments were as lighthearted. Halfway through his time in the Ohio Valley, Sunday traveled down to the Moundsville Penitentiary to deliver a sermon to 1,200 convicts; those same convicts would later send a large flower bouquet to Sunday to show their gratitude.15

Throughout the entire campaign, The Intelligencer kept a tally of how many people had “hit the sawdust trail” and how much collections money was raised. Select names of Wheelingites who had converted were mentioned in the paper every day so that residents could recognize their neighbors, friends, and colleagues. By the end, Wheeling had a total of 8,437 converts and $17,000 (about $446,858 in today’s currency) in collections—breaking both records at the time.16

“With Tear-Dimmed Eyes”

As Billy Sunday prepared to leave Wheeling after six weeks of proselytizing, “thousands of men, women and children with tear-dimmed eyes wept as though their hearts would break.”17 In his final remarks, Sunday extended his thanks to Wheeling, saying that “he has grown to like the citizens of this city better than any city he was ever in.”18 The Intelligencer reported that 10,000 residents of the Greater Wheeling area arrived at the train station to say farewell.19

After Billy Sunday’s departure, the Tabernacle was used for other meetings or religious services. However, by June of the same year, the building was torn down to make way for two new parks and the lumber sold to Scott Lumber Company to be repurposed.20 The first guest of entertainment at the new parks was the Moss Brothers’ Greater Shows Carnival and memories of the Tabernacle that took Wheeling by storm would soon fade.21

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 Lyle W. Dorsett, Billy Sunday and the Redemption of Urban America, (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1991), 23.

2 Robert F. Martin, “Foreward,” in The Sawdust Trail: Billy Sunday in His Own Words, William A. Sunday, (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2005), xii-xiii.

3 Ibid., viii.

4 Wendy Knickerbocker, “Billy Sunday,” Society for American Baseball Research, accessed December 21, 2020, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/billy-sunday/.

5 “Start To-Day to Haul Lumber for Billy Sunday Tabernacle at Twenty-Sixth Street. Work on Structure Starts Tuesday of Next Week–Many Committees Meet This Week,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, January 22nd, 1912, p. 9.

6 “Sunday Will Arrive Today,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, February 17, 1912, p. 6.

7 “Sunday Stated Last Evening,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, March 13, 1912, p. 1.

8 “Women Do Their Share of Work on Tabernacle,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, February 2, 1912, p. 9.

9 “Tabernacle is Completed,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, February 3, 1912, p. 5.

10 “Sawdust Trail Laid at the Tabernacle,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, February 2, 1912, p. 9.

11 ““Billy” Sunday Has Come To Town,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, February 19, 1912, p. 1.

12 The Wheeling Intelligencer, February 20, 1912, p. 13.

13 “Policeman’s Finger Bitten to the Bone; Others Viciously Hatpinned at Tabernacle,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, March 22, 1912, p. 1.

14 “Seven Thousand Sunday School Workers Parade,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, March 18, 1912, p. 8.

15 “Twelve Hundred State Convicts Promise to Lead Better Lives,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, March 12, 1912, p. 1.

16 “Converts and Collections,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, April 1, 1912.

17 “Breaks All Records During His Career,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, April 1, 1912, p. 1.

18 “Billy Sunday is Given $17,000 for the Labor is Worthy of His Hire,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, April 1, 1912, p. 10.

19 “Billy Sunday is Given $17,000 for the Labor is Worthy of His Hire,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, April 1, 1912, p. 10.

20 “More Play Grounds Wanted in the City,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, May 18, 1912, p. 9.

21 “Carnival Comes,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, June 10, 1912, p. 12.