“Magical.”

In a word, that’s what Jeannette Walls calls her childhood.

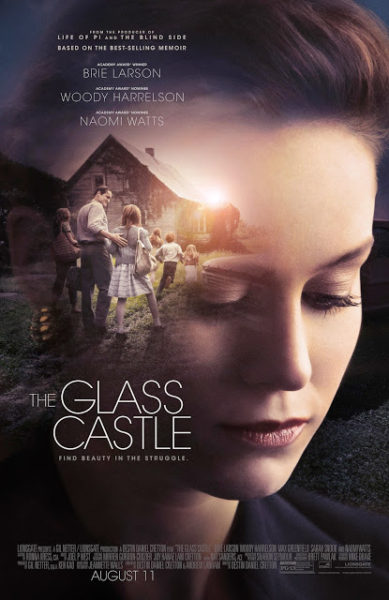

Surprised? If you have read her memoir, “The Glass Castle,” or have seen the movie based on the book, you might be.

Walls will speak about “Demon Hunting and Other Life Lessons” at 7 p.m. Thursday in College Hall at West Liberty Univerity, free and open to the public, as a part of the Hughes Lecture Series, named for Dr. Raymond Grove Hughes. Hughes was a popular professor at West Liberty from 1931 to 1970. No West Liberty student could graduate during this time without having taken one of his courses in grammar, composition, speech, journals or literature. His generous bequest established an endowed fund managed by the West Liberty University Foundation.

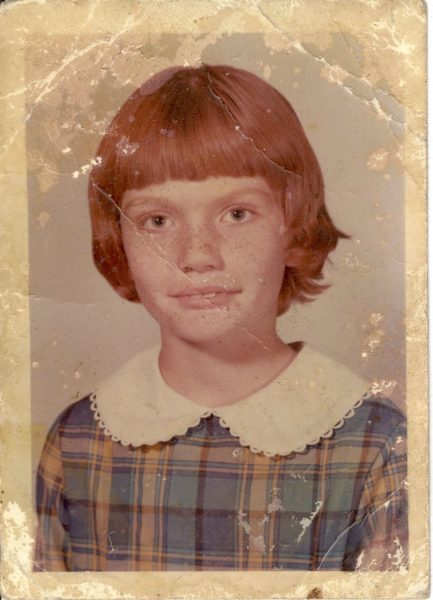

The author grew up in a figurative “briar patch,” without a lot of, shall we say, creature comforts — heat, running water, food, money. And along with the deprivation, she endured bullying, prejudice and molestation during the years the family spent in Welch, W.Va.

Jeannette was born in Arizona, and her family moved from place to place out west, pulling up stakes when her father lost his job or got in some sort of trouble. There was always trouble. Eventually, at her mother’s urging, they moved back to her father’s West Virginia hometown when Jeannette was around 11.

“We were always doing the skedaddle, usually in the middle of the night. I sometimes heard Mom and Dad discussing the people who were after us.” (page 19)

Now, she lives on a horse farm in Virginia, just a couple hundred miles — and a world — away from McDowell County, W.Va. She has a thermostat, which, as a child, astonished her when she saw that a little lever was all it took to warm the home of a classmate. And a fireplace — “but it’s more for atmosphere than to keep me warm,” she said.

“One of the great things about the way I was raised is that I will never take my thermostat or running water or grocery store for granted,” she said.

SHE NEVER FELT ‘UNLOVED’

Her mother, Rose Mary, had lots of good traits, but “mothering” wasn’t one of them. Her dad, Rex, was an alcoholic, and most likely bipolar.

But she never felt “unloved.”

Rose Mary, an artist, saw “beauty in everything. … Mom gave us the gift of optimism and belief in oneself.”

And her father — some called him a genius — “gave us the gift of dreaming and ambition and passion for the stars and for creating glass castles.”

Rex Walls had plans, on paper and in his soul, to build a “great big” house in the desert.

“It would have a glass ceiling and thick glass walls and even a glass staircase. The Glass Castle would have solar cells on the top that would catch the sun’s rays and convert them to electricity. … All we had to do was find gold. …” (page 25)

Rex gave them hope, she said. “When times got hard, he’d pull out the plans for the Glass Castle. That was about hope. At times of despair, it’s easy to give up.” But, hope and belief in oneself kept despair at bay.

About her mother, who now lives with her in Virginia, Jeannette said, “I’ve come to love her very, very dearly. As long I’m not looking for her to take care of me. She’s a phenomenal human being. The minute she’s asked to take care of anybody other than herself, she just can’t do it. And that’s one thing I’ve had to accept.”

STRENGTH, RESILIENCE, FEARLESSNESS

“If you don’t want to sink, you better learn how to swim.” Rex Walls (page 66)

If a deserted island is in your future, take Jeannette Walls with you.

“I’m the person you want to travel with. The airplane starts bumping, I’m fine, I’m fine. The hotel doesn’t have running water. This is fine, We just go buy a couple bottles of water. This is OK,” she laughed.

If you happen to be in a big city with Jeannette, she’ll look out for the muggers for you. “I got in trouble from my first husband,” with whom she lived on New York City’s Park Avenue. Upon seeing someone being mugged, Jeannette ran to the victim’s aid. “My husband was horrified. … It never occured to me not do that. And one time, I was being mugged, and no one came to my aid and was appalled, I was just shocked. I beat the crap out of the guy … and the guy ran off,” she said. “These things don’t scare me.”

“Little things don’t bother me. Big things don’t bother me.”

At the age of 3, Jeannette caught on fire while cooking hotdogs over the stove, and spent weeks in the hospital recovering from severe burns.

A few years later, Rex tossed her into the deep part of a natural sulfur spring, over and over and over, so she would learn to swim. Also during her young years, he taught her to shoot guns and throw knives. One time, he led the kids through a chain fence at a zoo where Jeannette pet a cheetah, much to the dismay of onlookers.

She learned to be fearless.

“I guess I was raised in a briar patch,” she said. “A certain degree of fearlessness is a very valuable gift to give a child. I’m not saying I was given it in the right way.” Her hearty laugh came through the phone line.

“How do we protect our children? … I think that’s one of the things people think about when they turn to my book. Do we protect them by taking them away from danger? Or do we protect them by exposing them in a limited degree to danger and teaching them to protect themselves, or do we throw them into the frying pan? I don’t think we do the last. I think my case was extreme. But I think there’s something to be said for exposing them to a variety of circumstances and showing them how to deal with the world.

“I think the knives and the fires and the guns and everything that I was exposed to — it was a valuable gift I was given. But the downside of it is that I walk around my life with a suit of armor, prepared to fight with anyone who looks cross-eyed at me. What I was unprepared for, the lesson I have had to learn is kindness and vulnerability – that those exist alongside the knives.”

THE POWER OF STORYTELLING

“The gift that people have given me, in exchange for coming clean about my story, is showing me this incredible generosity of spirit and softness, and they’ve taught me how to make myself more vulnerable. And it’s the beauty of storytelling. We share what we know and what we’ve learned.”

Sharing her story has changed people’s lives.

“After my book had come out, I got a gut-wrenching letter from one of my former co-workers. … ‘You had your secrets, and I had mine,’” the letter said. “My having written my book encouraged her to write hers.”

And in New York, a woman who was raised on Park Avenue, told her, “If my father had one time taken us kids out to discuss the stars, or if my mother had one time said, ‘don’t worry what other people think of you, you’ve got to be yourself,’ I wouldn’t be in therapy today.”

In a wealthy neighborhood in Dallas, where her memoir had initially been banned, she said, “The parents and the teachers, and, bless their hearts, the students, got together, and they said, ‘We need to hear about stories like this.’ And here’s the ultimate irony — I went to this school to talk, and afterwards a number of the kids came to me and said, ‘Thank you for telling your story because I had a problem with a relative doing inappropriate things.’

“People’s experiences may not be as extreme as mine, but what I think is very important and what is the great value in reading and storytelling is sharing these stories and learning, ‘Oh my gosh, my situation may not be identical, but we have a lot in common. We make these emotional connections. … We learn from each other.

A woman in a book club came up to her after a talk and told her, “Until we read your book, we didn’t know each others’ stories.”

“You know, the guns and the craziness and the wackiness that I dealt with was just one story. Not more shocking or more important or more complicated or more tragic or more wonderful than anybody’s story,” Walls said.

AND THE FAMILY WAS OK WITH IT

“Almost entirely positive,” Jeannette said of the family’s reaction to her memoir.

“Mom says she sees things differently. She doesn’t disagree with anything. My older sister, Lori, she finds the past more painful than I do. She couldn’t understand why the heck I’d want to revisit it.

“My kid sister (Maureen) was the most — to be frank — she was the most damaged. She didn’t fare so well, but she was fine about the book as well.”

Brian, her brother, a retired police officer who lives in Brooklyn, remembered the stories the same way, but with a different emphasis, she said.

“Some of the stories I tell as heartwarming, he just rolls his eyes.” For example, when her dad “gave” the kids stars for Christmas one year, Jeannette was fascinated, enthralled. (She chose Venus. — even if it wasn’t a star.) “Brian always saw right through my father’s B.S.”

And Rex? “I think somewhere in the cosmos Dad is grinning ear to ear, busting his buttons.” He died before the book was published.

RATED A FOR AUTHENTIC

“I loved the movie! I loved it,” she said.

A movie version of “The Glass Castle” was released last August — another way of getting her story out, especially to people who don’t like to read.

The story was a “complicated story to capture. I spent a lot of time on the set, and I was just stunned by the passion for getting it right, for trying to get across this complicated story,” Walls said. “You know they used my mother’s paintings in the movie.”

She got an email one day from the woman who did the set, that said, “There’s been quite a discussion here about the garbage pit. We need a large amount of garbage, but we had a discussion that our garbage would’ve been different from what the Walls’ garbage would’ve been. What was in the garbage pit?”

“If they’re that passionate about getting garbage right, then you gotta love them,” Walls said.

Jeannette was quite impressed with Woody Harrelson, who played Rex. “When I first saw him in character, I just started trembling and crying. Because he nailed it. He didn’t just play my father, he became my father.”

“Brie Larson (who played Jeannette) was … watching with these laser eyes, and she just started picking up my mannerisms, the way I hold my head, my weird ‘cackley’ laugh, and it didn’t feel invasive, but sort of surreal.” Larson also wore some of Walls’ clothing from the 1980s.

One of the scenes in the movie that absolutely delighted Jeannette involved the Welch High School cheerleaders. In the film, the cheerleaders were played by the actual cheerleading squad from Mount View High School in Welch. One of her former classmates is now the head of the cheerleading squad at Mount View. “She got her girls to make their own outfits … recreating the squad’s uniform from the 1970s.”

Jeannette said her mom also liked the movie and had this to say about it: “A little embarrassing but they did a good job.”

EDUCATION IS THE TOOL

“I’ve always believed in the value of a good education.” Rose Mary Walls (page 265)

Walls champions many causes, she said. But, “at the top of the pyramid is education.”

“It all comes back, in my opinion, to education. Education is the tool that you need. And it doesn’t necessarily make you smarter, but it often gives you the confidence and tools or packaging to get you to where you want to go.”

Walls’ teachers have always been an inspiration to her. In the first version of her book, she said, she included seven of her teachers. “But my editor said I could only include one.”

Education and self-esteem give people the power to move forward, she said. “It’s why I’m not bitter or angry — because my parents gave me the tools I needed. …”

“…. It’s funny, you know, because in so many ways she (her mother) dropped the ball. In other ways, she gave me the tools to pick up the ball and run myself. And it took me a long time to really appreciate it.”

While her parents gave her the love of learning and self-esteem, at one point, her dad came through with something quite unexpected.

After Walls moved to New York City at the age of 17 to live with her sister Lori, she finished high school, then went on to attend Barnard College. While she did receive grants, loans and scholarships, she was short $1,000 for her final year.

When her dad called one August day to go over her fall course schedule, she told him she was thinking of dropping out because she didn’t have the money.

“The hell you are,” Dad said. … “Dad called a week later and told me to meet him at Lori’s. When he arrived with Mom, he was carrying a large plastic garbage bag and had a small brown paper bag tucked under his arm. I assumed it was a bottle of booze, but then he opened the paper bag and turned it upside down. Hundreds of dollar bills – ones, fives, tens, twenties, all wrinkled and worn — spilled into my lap.” (page 264)

It was a total of $950. Plus, a mink coat. He won it all playing poker. Jeannette thought her parents needed the money more than she did, but they insisted she take it.

“So, when I enrolled for my final year at Barnard, I paid what I owed on my tuition with Dad’s wadded, crumpled bills.” (page 265)

FACING THE DEMONS

“All you got to do, Mountain Goat, is show old Demon that you’re not afraid.” Rex to Jeannette, whom he called Mountain Goat. (page 37)

Sure, she has “issues” from her past, she said. “And I always will.” But, they are “more things like … I buy in bulk. I don’t want to run out of food. Things like that. … Dealing with banks … I don’t like it.” … And “fitting in.”

She deals with her scars, her issues, by confronting them head-on, by facing them.

Jeannette fully believes that “it’s not what you’re given in life, it’s what you do with what you’re given.”

That’s what she’ll be talking about Thursday night at WLU.

“We’re all dealt a different hand., and you can feel sorry for yourself or be angry that you didn’t get a different hand, or you can take what you’ve got and play the ‘bejesus’ out of it. And I really believe that those of us who weren’t necessarily given the easiest life, sometimes we’re the lucky ones because we learn so much.

“Some say I’m not honest or realistic about how bad my life was. I would beg to differ with them. I am keenly aware of that. It’s a choice. It’s a choice to focus on the good. … That’s one of the gifts Mom gave me. … That’s the way we get out of poverty, more than any other way, in my opinion. It’s the way we see ourselves.

“Education is the great equalizer in life. Get a love of education, and you get a belief in yourself. Those are the two things, more than anything else, that can change your life to be whoever you want to be.”

PRESENT-DAY GLASS CASTLES?

“Oh, everything! I live in a beautiful house. I have four flush toilets. I think the Glass Castle was much less about the physical structure than about realizing your dreams. And in that way, I think my Glass Castle has been built 10 times over.

“I don’t regret a single thing. I’m sorry that my sister’s life didn’t turn out better — Maureen. I’m sorry that I couldn’t stop my father from drinking. But that’s not my life – that’s their lives. My life? I think I’m the luckiest person in the world. I really do. So many beautiful things have happened to me, and the thing is, if you are where you want to be, why regret how you got there?”

“Just remember,” her mom told her, “what doesn’t kill you will make you stronger.” (page 179)

• After nearly 38 years as reporter, bureau chief, lifestyles editor and managing editor at The Times Leader, and design editor at The Intelligencer and Wheeling News-Register, Phyllis Sigal has joined Weelunk as managing editor. She lives in Wheeling with her husband Bruce Wheeler. Along with their two children and two grandchildren, food, wine, travel, theater and music are close to their hearts.