In a dusty cardboard box that sits on a basement shelf in my house, there is a plain-looking red brick. It is lacquered and polished with a simple little gold plastic plate on its top that reads, “Kruger Street School 1907 – 1991.”

In a dusty cardboard box that sits on a basement shelf in my house, there is a plain-looking red brick. It is lacquered and polished with a simple little gold plastic plate on its top that reads, “Kruger Street School 1907 – 1991.”

Back in the late 1990s, it seemed like a good idea to fork over $10 for a physical reminder of a building that played such a key role in my life and in the lives of so many other Elm Grove children.

The old building was the site of good childhood memories. But it was also the site of a nightmare event that left me with deep physical and emotional scars. If not for a heroic rescue staged by my mother, Mabel, it probably would have happened twice. Maybe that’s why my Kruger Street School memento lies buried in a box in my basement.

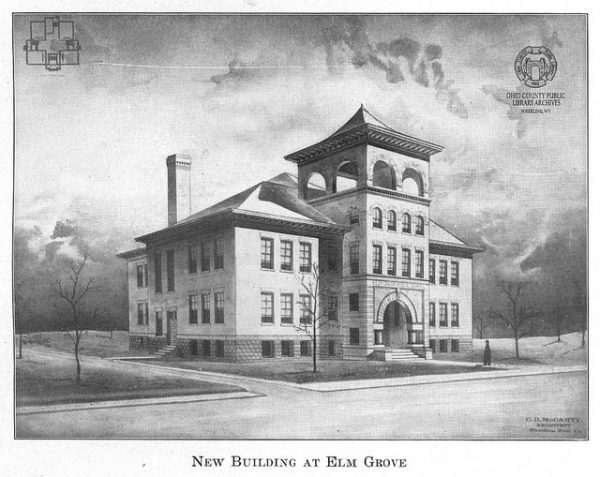

Kruger Street School, now the Kruger Street Toy and Train Museum, sits on 1.2 acres bordered by Columbia and Center Avenues. It is a red brick building trimmed with cut stone with a sandstone foundation. It has a spacious blacktopped surface on three sides it that is now the parking lot for the museum. In my day, it was a playground where Ohio County Schools workers annually applied yellow paint to outline hopscotch areas, a baseball diamond, a volleyball court, and a basketball court.

Inside, teaching occurred in four classrooms on the first floor and six on the second floor. They were big rooms with nice narrow wooden plank floors that were oiled and buffed every August just before students began another school year. The student desks were something that you only see in old movies today. They were short, bolted to the floor and to the seat immediately in front, and had a circular opening on the top that we were told accommodated inkwells in the olden days.

There were 30-foot wide common areas on each floor, but on the first floor an area had been adapted to be the school’s gathering place where children would sit on the floor to see plays on an elevated stage put on by the Junior Women’s League of Wheeling, or hear a concert by their peers banging away on toy instruments. It was also where the PTA held its meetings. Children were not invited to those meetings and I always wondered if they made parents sit on the floor.

My childhood encompassed the days when the government tried to ease the nuclear bomb fears of schoolchildren by convincing them through drills that ducking under their school desks could afford a degree of safety should the forces of evil unleash war upon us from the skies. At Kruger Street School, I don’t remember having many drills, probably because none of us could fit under the tiny desks. But, the teachers were diligent in explaining that those yellow and black signs posted over the stairway to the basement indicated that someplace down there was some sort of area that the government judged to be a safe place to wait out the post-bombing radioactive fallout for however long that would take.

My childhood encompassed the days when the government tried to ease the nuclear bomb fears of schoolchildren by convincing them through drills that ducking under their school desks could afford a degree of safety should the forces of evil unleash war upon us from the skies. At Kruger Street School, I don’t remember having many drills, probably because none of us could fit under the tiny desks. But, the teachers were diligent in explaining that those yellow and black signs posted over the stairway to the basement indicated that someplace down there was some sort of area that the government judged to be a safe place to wait out the post-bombing radioactive fallout for however long that would take.

That basement was a scary place. It’s where the bathroom facilities were located and it smelled like a strong combination of urine, floor wax and barely applied cleaner. The concrete floors were painted a dull burgundy color and they were so slippery when wet that some poor kid went down almost every day and sometimes that poor kid was me. There was a massive metal door on one wall with a tiny glass-covered peephole in it that was way too high for us to see through. But, we could sometimes see a flame-like reflection in the glass from our low angle of vision. Some said it was where the furnace was. Others believed it was a secret clubhouse that only janitors could use. Still others had more ominous explanations that had to do with missing children. All we knew was that none of us wanted to go in there.

The rest of the basement was a mystery. Someplace down there, we boys reasoned, there must have been a girl’s restroom and other strange rooms because there were sealed doors elsewhere on the interior walls.

There was a one-room third floor that few if any of us had ever seen. Above that was the spectacular bell tower that housed a tool that could signal panic if you were late for school, joy if it ushered in recess or lunchtime, and freedom if it was used to signify dismissal for the day. It was the school’s massive metal bell that only rang when our janitor, Mr. Pogue, pulled the rope that hung down to his second-floor closet.

There was a flagpole on the front lawn where fifth grade boys were entrusted to take down and fold the stars and stripes every day that it wasn’t raining or snowing. We never thought much about who put it up in the morning but we all figured it was Mr. Pogue who seemed to do just about everything around the school including mopping up vomit after the occasional gastronomical incident that seemed to plague K-5 kids.

The building’s “front porch” was an ideal after-school hours fort where boys like me who were lucky enough to have plastic replica Daniel Boone flintlocks could defend the frontier against the attacking Indians of our imaginations. Once, just after Daylight Savings time was invoked, a pal and I lost track of the time and stayed out so late playing in our Kruger Street makeshift fort that my family instigated a panicked neighborhood dragnet to discover my whereabouts.

This school building was a special place. It was where I:

- Learned how to read in Mrs. Morris’ first grade classroom

- Donned a clown’s costume in second grade and danced around a Maypole on the front lawn to celebrate the arrival of Spring

- Mastered the grace of cursive writing in third grade

- Learned of the death of John F. Kennedy as I stood frozen on the big black iron fire escape just outside my fourth-grade classroom where my teacher, Miss Fritz, had a radio blasting news coverage and she and a few classmates sat sobbing in shock

It was also where my worst childhood memory was born. On a crisp October day in my fifth-grade year in 1964, along with 16 other boys from my class, I was ordered to empty my pockets, bent over the principal’s desk, and administered four hard whacks with an unfolded leather belt for an unknown infraction committed by two anonymous classmates that had offended a rookie first-grade teacher. No one took the blame for whatever had happened.

“It’s like in the Navy,” I remembered the principal smirking when he signaled his devilish intention. “When one crew member screws up, everybody gets punished.”

“It’s like in the Navy,” I remembered the principal smirking when he signaled his devilish intention. “When one crew member screws up, everybody gets punished.”

I had bruises the size of potatoes on my hip. Other kids were bleeding. We all went home crying to outraged parents who stormed the ensuing PTA meeting with pictures of injuries and demands for disciplinary action against the principal. The incident would have been featured news on television and web sites today. But then, nothing came of the outrage and the incident seemed to fade away until my final day of class at the school when the same principal tapped me on the shoulder and ordered me to appear in his office after school. I may have been just 10 years old but I was no fool. I smelled the revenge all over the man who seemed to really resent how offended the parents had been over his earlier disciplinary action. My fifth-grade teacher had a telephone in her classroom and I borrowed it to call in air support.

The principal was pretty good at beating boys half his size, but he was no match for the ire of Mabel Minns Griffith who arrived at the school with the subtly of a SWAT team and the focus of a mama grizzly. My mother delivered a relentless verbal attack on the wayward administrator. He had few opportunities to respond and eventually gave up the fight, ordering Mabel to take her “angel child” and go home.

That was the last time I set foot in Kruger Street School for many years. I savored my return in the early 2000s and explored what had become, by then, the Toy and Train Museum with an eye toward recalling the good memories rather than the bad.

The bell of Kruger Street School no longer rings and children no longer populate the playground to play with those big dark red textured inflatable recess balls that always made a distinctive “boing” noise with every bounce. The old building is much quieter that it was when kids were its main business. But, Wheeling is lucky that she is still with us and lives on in a new life when so many other memory-laden structures are gone forever.

The bell of Kruger Street School no longer rings and children no longer populate the playground to play with those big dark red textured inflatable recess balls that always made a distinctive “boing” noise with every bounce. The old building is much quieter that it was when kids were its main business. But, Wheeling is lucky that she is still with us and lives on in a new life when so many other memory-laden structures are gone forever.