Right now, people are walking in Oglebay Park. Some walk with dogs, some run through the woods. Some walk with a cane or motor along in an electric power-chair. Parents push strollers, and kids run ahead, around and behind. Feet are adorned with hiking shoes, sneakers or flip-flops as they traverse dirt, grass and pavement. This is the life of the Oglebay trail system.

A Long History

Creation of the trail system began in the fall of 1927. By 1938, 10 miles had been completed by park employees. They had assistance from the Boy Scouts and the Civilian Conservation Corps, a work program for young, unmarried men that had a camp in Oglebay in 1936-37. Workers had to clear paths through the forest, navigate steep hillsides, and construct stone and wooden bridges over streams.

If you flipped through The Wheeling Intelligencer in 1929, you’d come across a weekly column called “Observations from Oglebay.” One week, it featured information about picnicking. Another offered a tidbit about family vacation camps (a room cost $1 for a single night and 50 cents for each additional night). On Oct. 1, 1929, “Observations from Oglebay” invited locals to visit the park’s many trails.

Just park your car at the mansion and roam the many miles of footpaths and enchanting trails to your heart’s delight. You’ll climb a knoll and obtain a magnificent view of the surrounding country. Then the trail will wind slowly through the woods to the ravines stretching below, opening to the nature lover all the joys of the wild, the bubbling of the brooks and the flash of the sunlight on the leaping cataracts. You’ll hear the chirping of the songbirds and catch glimpses of the abundant wildlife.

Conservationist and nature educator Alonzo Beecher “A.B.” Brooks served as Oglebay Park’s first naturalist. He was known for his Sunday morning nature walks, during which he led locals through the woods to identify bird species. (Walks were advertised in the newspaper; breakfast was served over an open fire at 7 a.m.) Along the way, he would recite poetry and teach participants about trees, flowers, insects and mammals in the park. The popularity of Brooks’ walks grew over the years; he began with two hikers on a trip to the waterfall on April 14, 1928. By 1938, Brooks had led 1,200 nature walks and over 50,000 people along the Oglebay Trails.

Conservationist and nature educator Alonzo Beecher “A.B.” Brooks served as Oglebay Park’s first naturalist. He was known for his Sunday morning nature walks, during which he led locals through the woods to identify bird species. (Walks were advertised in the newspaper; breakfast was served over an open fire at 7 a.m.) Along the way, he would recite poetry and teach participants about trees, flowers, insects and mammals in the park. The popularity of Brooks’ walks grew over the years; he began with two hikers on a trip to the waterfall on April 14, 1928. By 1938, Brooks had led 1,200 nature walks and over 50,000 people along the Oglebay Trails.

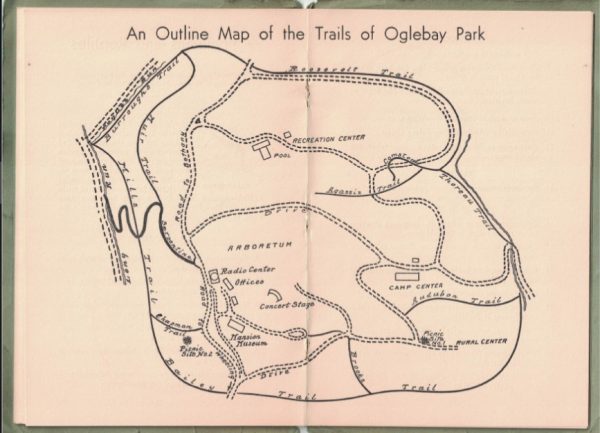

Today, in the Schrader Environmental Center library, you can find a 40-page pamphlet written by A.B. Brooks called The Trail Guide for Those Who Follow the Nature Trails at Oglebay Park. Published by Oglebay Institute as an educational bulletin, it sold for 10 cents in 1938. The cover has faded, and the pages have yellowed over the last 80 years. The bulletin covers Oglebay Park geology, wild plants, trees in the park, amphibians and reptiles, a trail map, birds, mammals and signs visitors would have seen along the trails. (It’s interesting to note that, in 1938, the white-tailed deer was not on the list of mammals a hiker could expect to see. The park had just become a state wildlife refuge in 1935.)

The trail guide also depicts the trail system at the time of publication.

The Trails Today

Today, visitors to Oglebay Park enjoy more than 15 miles of trails, both paved and wooded. You can still find shaded ravines, tumbling streams and hear birdsong as you walk. The Susan Wheeler Walking Trails and the Arboretum Trails offer an accessible way to experience Oglebay’s gardens, museums and lakes. Visitors of all abilities can utilize the paved surfaces, which cover 4.5 miles and provide the smoothest and easiest way to see the park’s main valley. Through various habitats and elevations, the interlacing nature of the trails allows you to create a different path every time you visit.

Some guests walk, and some run. Jesse Mestrovic, Wheeling’s director of parks and strategic planning, runs the trails at Oglebay. An avid outdoorsman, he knows the paths well.

“My favorite trail is probably the Driehorst Trail because you start at Falls Drive,” he said. “It’s a nice, peaceful stream area that has additional waterfalls. It’s not a lot of miles, but once you spit out by the Pine Room and the pool, you can do multiple loops around the lake. There are various levels and tiers, and then you can dip back into the woods by Schrader Environmental Center and come out by the waterfall.”

Mestrovic, who also runs at Wheeling Park, enjoys the opportunity to create variety in his workouts.

“I like the terrain. I like the variation of rolling hills versus steep hills versus nice, level, flat areas,” he said. He runs with his white dog, so on particularly muddy days, he sticks to paved areas and adds traction cleats to his shoes in the winter. Runners who want to monitor their mileage can use apps like Map My Run to lay out a specific course or distance and record their progress. In addition, WVU has included Oglebay’s trails in their West Virginia Trail Inventory database. Using GIS technology, each trail is visible on the map with information about distance and the surface type (e.g. paved, gravel, dirt, etc.).

Mestrovic is in good company. Ohio Valley runners find many opportunities to enjoy the paths. For the park’s 90th birthday in June, runners with two legs and four gathered for a celebratory 5k walk/run along the Susan Wheeler and Arboretum Trails. They ran again on the Fourth of July and yet again on an August night for a Glow in the Dark 5k. On Nov. 3, the Mountain East Conference held its cross country championships in Oglebay.

But if you’re not a trail runner or even a fast mover, the health benefits of walking are well established. According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), walking is a good way to lose weight, curb sugar cravings, reduce the risk of cancer and the intensity of joint pain, and boost the immune system. And while you may walk around your own urban neighborhood, there are significant benefits to walking in nature that you can’t find in a city. City dwellers have a higher risk for anxiety, depression and poor mental health than do those who live in the country. Researchers at Stanford University conducted a study on the psychological effects of urban living. They found that people who walked through green areas populated with trees and shrubs were more attentive and felt happier than those who walked along a busy road. Moreover, they found a tendency for urban walkers to brood or ruminate on their walks, which can be a precursor to poor mental health. The activity in the prefrontal cortices of these city-strollers indicated negative activity in that area of the brain. The scientists also discovered that volunteers who walked in nature for the same amount of time showed a decrease in brooding and rumination. Children with ADHD show improvement in symptoms after a hike and sleep better. Nature actually changes the brain.

But if you’re not a trail runner or even a fast mover, the health benefits of walking are well established. According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), walking is a good way to lose weight, curb sugar cravings, reduce the risk of cancer and the intensity of joint pain, and boost the immune system. And while you may walk around your own urban neighborhood, there are significant benefits to walking in nature that you can’t find in a city. City dwellers have a higher risk for anxiety, depression and poor mental health than do those who live in the country. Researchers at Stanford University conducted a study on the psychological effects of urban living. They found that people who walked through green areas populated with trees and shrubs were more attentive and felt happier than those who walked along a busy road. Moreover, they found a tendency for urban walkers to brood or ruminate on their walks, which can be a precursor to poor mental health. The activity in the prefrontal cortices of these city-strollers indicated negative activity in that area of the brain. The scientists also discovered that volunteers who walked in nature for the same amount of time showed a decrease in brooding and rumination. Children with ADHD show improvement in symptoms after a hike and sleep better. Nature actually changes the brain.

We shouldn’t be surprised by these findings. The idea of healing in nature goes back thousands of years, though most of us are probably more familiar with the meditations of Henry David Thoreau and his years spent on Walden Pond. He noted the power of green spaces in Walden:

“We need the tonic of wildness … At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature.” 75 years later, A.B. Brooks agreed. He made it his life’s work to share the natural world with the people of the Ohio Valley.

Future of the Trails

Mike Potts, director of facilities and recreation, said the park continues to improve the trail experience.

“We’ve opened a few new trails within the last 18 months, which are the Driehorst and the Roosevelt,” he said. Currently, the trails crew is working on a connector behind the zoo, from the Hardwood Ridge Trail to the Bridle Trail, that will complete a circle around the park. Fortunately, the hardest work was done decades ago, in Oglebay’s early days.

“All of the trails have been more restorations than they are creation of new, with the exception of some connectors and different stuff trying to connect loops together,” Potts said. “The Serpentine [Trail] was a restoration. The Driehorst, all those trails were already there.” The Serpentine Trail served as Earl W. Oglebay’s driveway at the turn of the century. Its switchbacks gave carriage riders plenty of time to anticipate their arrival at the Oglebay estate at the top of the hill. The trail was restored and re-opened in 2016. It connects with the 2-mile Bridle Trail.

Five Ways to Enjoy the Trails

Whether you’re a regular walker or have yet to stretch your legs, here are five ways you can enjoy the trails at Oglebay:

- With a dog

Oglebay Park is dog-friendly. While young dogs will enjoy a splash in the creek or a roll in the leaves along the Hardwood Ridge or Bridle Trail, older dogs with stiff joints may appreciate the gentle slopes and paved surfaces of the Susan Wheeler Walking Trails. It’s an excellent way to exercise and socialize your dog. Very young pups benefit from controlled exposure to a variety of experiences, people and other pets. Dogs who chew the couch when they’re bored are far less likely to do so when they’re tired; a walk can save your furniture and your sanity. Dogs should be leashed, and waste bags are appreciated.

- On wheels

The Susan Wheeler Walking Trails provide a smooth surface for jogging strollers, wheelchairs and rollerblades. For thrill-seekers, the park’s new mountain biking courses offer both beginners and experienced riders a chance to enjoy the trails. According to Mike Potts, there are plans to improve and expand the mountain bike terrain in the future. You can rent bikes at the Par 3 rental center or at Schenk Lake. All paths, paved and wooded, are open for mountain biking.

- In the winter

Oglebay is a different place in the winter. Hikers, dog-walkers, and trail-runners know winter offers not only a change in scenery but also some distinct advantages in the forest. After the first freeze, weeds disappear, poison ivy retreats, and perhaps most importantly, so do insects like mosquitos and ticks (the latter being troublesome for both humans and dogs). A winter walk along the Hardwood Ridge Trail gives hikers a peek at the park’s many sugar maples as they release their bounty. Frozen waterfalls look spectacular, and a fresh snowfall blankets the park in heavy silence. Winter is also a great time to try your hand at black and white photography.

- With a child

Technology and its constant presence in our lives are severing our children’s connection to nature. They spend more and more time looking at screens, but research indicates children who spend time in nature are happier, healthier and more successful in school. In Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder, author Richard Louv remembers his own childhood playing outside with sticks and rocks, under and in trees, watching ants, caterpillars and spiders. It’s a past many of us recall well.

Louv writes, “We have such a brief opportunity to pass on to our children our love for this Earth, and to tell our stories. These are the moments when the world is made whole. In my children’s memories, the adventures we’ve had together in nature will always exist.”

Oglebay trails lead children to Schenk Lake and the playground, as well as the Schrader Environmental Center and the waterfall. Older kids can take the lead in the woods, while strollers easily roll along the Susan Wheeler and Arboretum Trails. Sometimes, a patch of grass or a fistful of pinecones is all your little one needs to connect with nature. Unstructured time allows children and caregivers time to relax and bond. Kids’ brains thrive outdoors.

Oglebay staff hear a steady stream of stories from visitors. “We always visited the ducks on Schenk Lake,” they might say, or “My dad took me on Sunday hikes behind the Schrader Center.” Most of those stories go back to the tellers’ childhoods when beloved outdoor traditions began. They’re traditions worth repeating.

- By yourself.

In Japan, nature therapy has become an essential part of preventative health care. Shinrin-yoku means “forest bathing” in Japanese. It’s not a bad idea. Given what we know about nature exposure, a quiet, solo hike can offer not only health benefits but also a time to unplug. Leading your young ones through the arboretum or flying down the bike paths satisfies your active brain, but learning to sit with yourself can often be a more challenging endeavor. Whether you’re hearing the rush of a waterfall, the call of a sharp-shinned hawk or the wind in the pines on the picnic knob, it’s important to listen in these moments of calm.

Oglebay Park’s trail system offers a unique experience for everyone, and everyone uses the trails differently. A.B. Brooks once wrote that it was the desire of the park to give every visitor the greatest possible amount of information and pleasure during their stay. He found what he was looking for amidst the hills and in the forests, as have generations of people since. Nature has so much to tell us about ourselves. Out there, we can hear what it says.

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.