To those not suffering from substance use disorder, the solution to the current opioid epidemic seems perfectly obvious — users should pull themselves up by their proverbial bootstraps, kick their addictions cold turkey, then live happily ever after. But unfortunately, that’s not the way it happens in the very real and often dark world of addiction.

According to the Wheeling-Ohio County Health Department (WOCHD), Ohio County has the sixth-highest overdose rate among all 55 counties in the state of West Virginia. This statistic means that our local health department has quite a bit of experience helping residents during active addiction. Three years ago, the health department opted to create what was then only the third county-run Harm Reduction program in the Mountain State.

According to the Wheeling-Ohio County Health Department (WOCHD), Ohio County has the sixth-highest overdose rate among all 55 counties in the state of West Virginia. This statistic means that our local health department has quite a bit of experience helping residents during active addiction. Three years ago, the health department opted to create what was then only the third county-run Harm Reduction program in the Mountain State.

WHAT IS HARM REDUCTION?

Harm Reduction is a public health philosophy and intervention service that seeks to reduce the harms associated with drug use and less-than-effective drug policies. Such programs offer practical strategies for reducing negative health consequences associated with drug use. Some of the more detrimental effects of intravenous drug use, in particular, are the spread of HIV, hepatitis C and other bloodborne diseases. Serious tissue infections and other complications are also common and costly to treat.

A guiding principle behind harm reduction is that every interaction with a drug user is a potential opportunity to encourage him or her to make positive changes. Ideally, that would mean seeking long-term treatment for his or her substance use issues. But again, this is the real world, and not every user is willing or able to choose recovery the moment it is offered. Harm reduction models help to keep them as safe as possible until they are ready to accept help.

At the  WOCHD, the program takes a three-pronged approach. The first is education. Whether it’s in the clinical setting at the City-County Building or on the street with Project HOPE, the health department’s staff makes educating the public about drug abuse a top priority. Every conversation with a patient is a chance to offer him or her the necessary support to take that first step on the road to recovery.

WOCHD, the program takes a three-pronged approach. The first is education. Whether it’s in the clinical setting at the City-County Building or on the street with Project HOPE, the health department’s staff makes educating the public about drug abuse a top priority. Every conversation with a patient is a chance to offer him or her the necessary support to take that first step on the road to recovery.

The second facet of the program is the department’s naloxone (brand name: Narcan) training and distribution initiative. Wayland Harris, threat preparedness director of the WOCHD, says that the training program began after the state of West Virginia passed SB335 in 2015. This bill allowed naloxone to be prescribed not only to first responders but to drug users themselves and the friends and family closest to them.

“Since that time, our naloxone education program has trained and certified several hundred local citizens and first responders,” Wayland reports. Wayland, a former Wheeling Fire Department firefighter and paramedic, received specialized training to conduct the Narcan education program and now presents it in locations throughout the state. He has also trained many first responders in the local area, most of whom carry Narcan at all times. Locally, it is carried by all Ohio County Sheriff Department deputies, all local volunteer and city fire departments, and many other first responders. Currently, the Wheeling Police Department does not carry Narcan in its cruisers. Chief Shawn Schwertfeger tells Weelunk that the Wheeling Fire Department’s response time is so quick within the city limits that he does not feel it’s necessary for his officers to carry it.

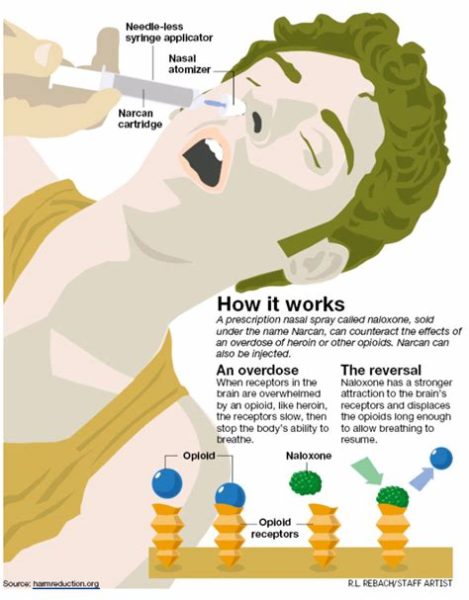

WHAT EXACTLY IS NARCAN AND HOW DOES IT WORK?

Narcan is a life-saving drug that can revive victims of opioid and opiate overdoses. Opioid drugs such as heroin, fentanyl, oxycontin and oxycodone cause overdoses by slowing a person’s breathing to a dangerously slow and eventually non-existent level. When administered correctly, Narcan works to counteract the opioid in the victim’s system and restore breathing to more normal levels. The drug usually works within a short period of time, allowing first responders time to get the patient to a hospital.

TRAINING AND CERTIFICATION

TRAINING AND CERTIFICATION

The training provided by the WOCHD teaches participants the basics about opioids, overdoses and Narcan. Trainees will be taught to recognize the signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose, properly administer Narcan and know the necessary follow-up protocol. At the conclusion of the hour-long class, each participant will receive a certificate of completion, which is required to receive a prescription for Narcan. Trainees also receive a WOCHD-issued prescription for Narcan that can be filled at most local pharmacies. In contrast to the memes shared freely on social media, Narcan is not free of charge. The current price of the drug varies by pharmacy and can run up to $150 or so. Some health insurance plans will cover some or all of the out-of-pocket expense. But think of it this way: Naloxone — investment of $150. Saving the life of a friend or family member — priceless.

Naloxone — investment of $150. Saving the life of a friend or family member — priceless.

WOULD YOU KNOW WHAT TO DO IF A SUSPECTED OVERDOSE OCCURS?

If not, you may want to consider scheduling a training session and learning how to react. Wayland will bring his educational presentation to church, school or office groups at no charge. He can be reached by phone at 304-234-3682 or by email at Wayland.W.Harris@wv.gov.

NEEDLE EXCHANGE PROGRAM

The final component of the Health Department’s Harm Reduction initiative is the needle exchange program. This program allows users one-for-one exchange of used needles and syringes. The program also accepts used and discarded needles from the public as well as from first responders and other businesses and governmental agencies. Howard Gamble, WOCHD administrator, oversees the needle exchange and says that they typically disburse between 150-300 needles during a single exchange clinic.

“Since 2015, we have disbursed about 23,000 clean needles,” Gamble says. “When we started this program in 2015, it was a new venture for public health agencies in West Virginia. At that time, only two other public health agencies were planning or doing exchanges. Our program differs from other public health and non-public health needle exchanges in that we operate under a county board of health regulation which allows and permits us to operate an exchange for the purposes of reducing disease. In order to develop our program, we met or communicated with local, county, state and federal legal authorities. We also met with several social and healthcare organizations, including our partner, Northwood Health Systems, so that we all understood our plans, goals and objectives. With the support of all of these agencies, including the law, legal and healthcare community in Ohio County, we felt safe in launching our program.”

Anyone with a need to participate in the needle exchange should feel safe, as well. Although some basic demographic data is collected for analysis purposes, participants are not required to disclose any personal information such as name, address or birth date.

Needle exchange clinics are held each Friday from 1-4 p.m. at Northwood Health Systems, 2121 Eoff St., Wheeling. Individuals are also welcome to visit the Health Department at 1500 Chapline St., Suite 106 for needle exchanges. Their office is open weekdays from 8:30 a.m. until 4:30 p.m.

IS IT WORKING?

Is the Harm Reduction program positively impacting the opioid crisis? Indeed it is, although it’s difficult to quote specific statistics of improvement at this point. Wayland says that data analysis of patient demographic information is a relatively new technology and it may take a while to see a positive trend in numbers. However, there’s no doubt that this program is educating the public, preventing disease and saving lives.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Gamble says that maintaining and financially supporting the current program is vital. Going forward, he would also like to see other locations set up for the needle exchange program. The health department may also consider placing needle drop boxes in some public areas. These drop boxes would be emptied and maintained by the WOCHD.

A gap in care seems to exist at the point where overdose victims are released from the hospital or emergency room. Some municipalities are putting together programs that would connect patients with a public health or social services professional when they are discharged from a healthcare facility following an overdose.

A gap in care seems to exist at the point where overdose victims are released from the hospital or emergency room. Some municipalities are putting together programs that would connect patients with a public health or social services professional when they are discharged from a healthcare facility following an overdose.

“There are programs starting in West Virginia to do this, and we are now looking at funding to support this in our area,” Gamble reports. “Funding is always a concern for any public program; let alone a public health program. If the need in West Virginia is as great as the data suggests, funding needs to be more direct to public health agencies in each county. Our needle exchange receives no direct financial support from the state health department.”

In fact, he says, many West Virginia counties who experience even higher rates of opioid-related issues than Wheeling does still do not have a harm reduction program in place because of lack of funding.

If West Virginia is to overcome the current public health crisis of opioid addiction, healthcare professionals need all possible tools at their disposal. Harm reduction programs such as this one are an integral piece of the recovery puzzle. Before we can put an end to this epidemic, we must first do no harm.

To contact the Wheeling-Ohio County Health Department about their Harm Reduction efforts, call 304-234-3682 or visit the website.

• A lifelong Wheeling resident, Ellen Brafford McCroskey is a proud graduate of Wheeling Park High School and the former Wheeling Jesuit College. By day, she works for an international law firm; by night, (and often on her lunch breaks and weekends) she enjoys moonlighting as a part-time writer. Please note that the views expressed in her writing are solely her own and do not necessarily reflect those of anyone else, including her full-time employer. Through her writing, Ellen aims to enlighten others on causes close to her heart, particularly addiction, recovery and equal rights. She and her husband Doug reside in Warwood with their clowder of rescued cats, each of whom is a direct consequence of his job as the Ohio County Dog Warden. Their family includes four adult children, their spouses and several grandkids.