Disclaimer: Weelunk cares about your health and safety. This article is intended to provide information on the history and traditions of these foods. It is critical to your health and safety that you properly identify wild floral before touching it, let alone eating it. Before touching or eating anything on your own, we recommend seeking the input of a naturalist or other certified expert, especially if you are uncertain of anything in the wild. Additionally, if you have concerns about allergic or other medical reactions to any of the foods listed in this article you should discuss them with your doctor before deciding to eat them. Weelunk and its contributors shall not be held directly or indirectly liable for any action that a reader decides to take as a result of this article. This includes any negligence or tort that rises from those actions. Stay safe and enjoy West Virginia’s food traditions!

Food helps paint a picture about people. It blends the colors of their cultural heritage, their present socioeconomic status and, perhaps, future. Mountaineers are resourceful, independent and resilient. Those qualities come through in the food that we’ve known for generations and continue to eat today.

Our relatives utilized simple ingredients and whatever was available from the wild, garden and farms — and made it delicious. Born out of necessity, they’re foods like ramps, salt rising bread, paw paws, pepperoni rolls, buckwheat cakes and so many other foods — foods as wonderful and simple as the people in the mountain kitchens where they originated. Some are more popular than others today, but they all continue to define a part of the wild and wonderful state. While it’s easy to forget tradition in a modern world, food traditions must be preserved in order to continue painting the picture that makes people Mountaineers.

RAMPS — WHAT’S THAT SMELL?

As the clouds begin to part after a long winter, patches of those pungent greens springing from the Appalachian hollow (pronounced haa·lr) floor are a sight for sore eyes. A ramp is simply an old-English term for a type of wild leek that has a strong smell and unique taste. Their taste is similar to a combination of strong garlic and onion. The word “ramp” was used primarily in Southern Appalachia, but the word has become more widely used because of an increase in popularity of the wild plant. In West Virginia, however, “digging a mess of ramps” is an indelible part of the cultural fabric.

There are endless ways to cook ramps. Because Mountaineers typically had a good supply of potatoes and never let leftover bacon grease go to waste, the old staple is ramps and potatoes fried in bacon grease. Some also have beans and cornbread with their “ramps and taters.” Because the growth of ramps coincides with trout season, many enjoy their ramps with fresh-caught trout. Many even enjoy ramps in the raw. However they’re eaten, those wild leeks make a long winter seem not so bad!

In Elkins, West Virginia, they celebrate their love for ramps with the annual Ramps and Rail Festival.

“The festival was originally designed as a way to promote local businesses, organizations and artists,” said Anne Beardslee, executive director of the Elkins Depot Welcome Center. “Because it’s one of the first events of its kind of the season in the area for some of our vendors, the event makes up a large percentage of their annual business.

“The festival has grown to what is basically maximum capacity with around 20 food vendors and 30 craft vendors each year, some of whom come from neighboring counties or other states, like Ohio,” she said.

At one time, Mountaineers harvested enough ramps to feed themselves and their families. Today, in large metropolitan cities, ramps are sold at high prices and are in high demand in many restaurants. This has led to discussions regarding sustainability efforts for the plant. One variety, Allium tricoccum var. tricoccum, is currently listed as of “special concern” in Maine, Rhode Island and Tennessee with the USDA. The plant is also listed as “commercially exploited” in Tennessee. The second variety, Allium trioccum var. burdickii, is listed as “endangered” in New York with the USDA, and “commercially exploited” and “threatened” in Tennessee. Many forests and parks have placed restrictions or banned the harvesting of ramps because of overharvesting.

Before digging, make sure research is done regarding applicable laws or restrictions. Additionally, make sure that you understand the best sustainability methods, including the sizes of patches to dig from and the proper method of digging. This will help to make sure that future generations will have access to ramps for years to come.

PEPPERONI ROLLS — APPALACHIAN INGENUITY AND IMMIGRANT SPIRIT

Mountaineers have been trying to make food easier to eat on the job for decades. Thankfully, the result of one of those experiments was the pepperoni roll, the highly extolled unofficial state food. Mountaineer miners carried sticks of cured meat, such as pepperoni, and bread in their lunch pails as something easy to eat in the cold, dark mines for many years. According to the Marion County CVB website, Giuseppe “Joseph” Argiro, an Italian immigrant and miner in Fairmont, West Virginia, decided to bake pepperoni into the bread. The convenient lunch became so popular with his fellow coal miners that Giuseppe quit mining and opened Country Club Bakery in 1927. The business still makes pepperoni rolls today in Fairmont! The pepperoni roll remains a great example of immigrant’s rich history of contributions to West Virginia.

A pepperoni roll is basic. They’re a staple at everything from WVU tailgates to day hikes in West Virginia’s beloved state parks. Traditionally, they’re just cheese and pepperoni baked into bread. Many families in West Virginia have closely guarded pepperoni roll recipes — passed down from their grandparents and great-grandparents — covered in flour in other remnants of past baking. The recipes explain how to get that bread just right. While simple, there is no doubt that the food created by an immigrant miner is beloved throughout the state of West Virginia today.

PAW PAW — THE UNKNOWN AND THE INFAMOUS

While it is incredibly unique, many today have never even heard of a paw paw tree and definitely have not eaten its fruit. However, if you’ve ever seen a very small tree with a semi-tropical appearance that looked out of place in the hills and hollows of Appalachia, it may have been a paw paw. The large fruit of the paw paw is the largest naturally grown fruit in North America. The fruit, which ripen in September and October, have a banana-mango, custard-like favor.

While it is incredibly unique, many today have never even heard of a paw paw tree and definitely have not eaten its fruit. However, if you’ve ever seen a very small tree with a semi-tropical appearance that looked out of place in the hills and hollows of Appalachia, it may have been a paw paw. The large fruit of the paw paw is the largest naturally grown fruit in North America. The fruit, which ripen in September and October, have a banana-mango, custard-like favor.

Chef Matt Welsch of the Vagabond Kitchen in Wheeling, West Virginia, has found creative ways to prepare the unique wild fruit over the years. “We have made paw paw pudding and worked with a local cheesecake maker to create paw paw cheesecake in the past,” Welsch said.

However, there are a few challenges with paw paws as well, which has prevented them from becoming more popular in the culinary world.

Welsch, who spent years traveling to better understand food traditions, continues to be an adamant defender of those traditions.

“They [paw paw] can be difficult to find in any significant quantity and are kind of difficult to process.”

As paw paws begin to ripen in early fall, check with your local restaurants to see if they’re offering any desserts featuring the unique wild fruit. Some fairs and festivals in Appalachia during the fall will even feature ice cream and other foods made with paw paws.

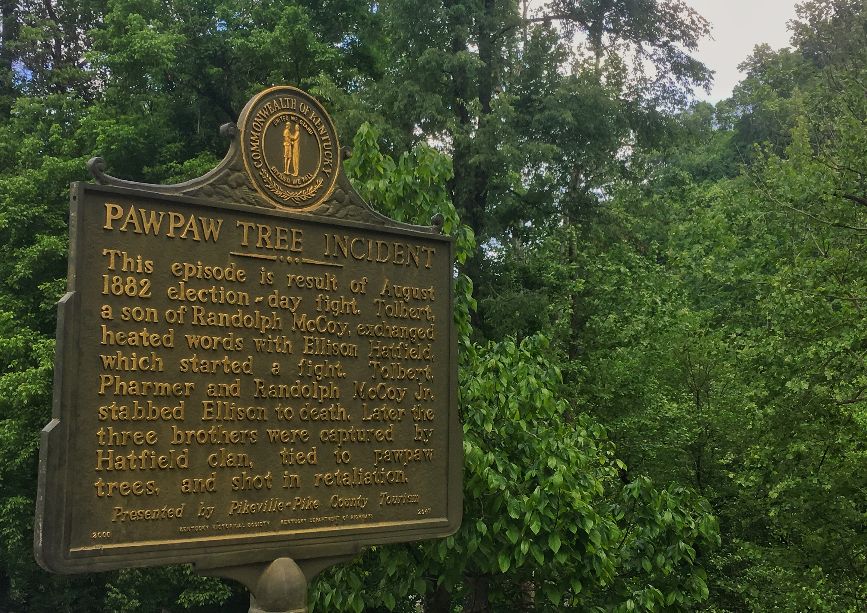

Paw paws have a unique place in the infamous history of West Virginia as well. One of the major events in the Hatfield-McCoy feud surrounded the “Paw-Paw Tree Incident.”

According to the Explore Kentucky History Team, in 1882, Ellison Hatfield was severely injured in an incident with Tolbert, Pharmer and Randolph McCoy Jr.

William “Devil Anse” Hatfield and the Hatfield forces took the McCoy men prisoner in West Virginia in retribution. If Ellison survived his injuries, Devil Anse would free them. However, if he did not, they would not live. Ellison Hatfield succumbed to his injuries. The McCoy men were taken across the Tug River to Kentucky from West Virginia where they were tied to paw paw trees and executed.

SALT RISING BREAD — GENERATIONS OF DEPENDING ON THE MICROBES

Salt rising bread is another food that was born out of the necessity — the necessity of early Appalachian settlers to utilize what was available in order to provide for their families. In the isolated West Virginia hills, early settlers may not always have been able to travel to purchase yeast and other supplies. Therefore, like many other things, their resourcefulness kicked in, and they created this bread.

Salt rising bread is unique. It depends on microbes to help the bread to rise rather than yeast, a commodity many early Appalachian settlers did not have available. It’s a fermentation process that is very slow and leaves the bread with a very unique “cheesy” taste and smell.

The Appalachian tradition of making salt rising bread has been passed down for generations, but faded in popularity. However, Rising Creek Bakery and Café in Mt. Morris, Pennsylvania, has led the charge to carry on the tradition of salt rising bread. In addition to its retail location, the bakery ships salt rising bread across the United States. (With the current COVID-19 pandemic, it is wise to contact the Rising Creek Bakery and Café regarding ordering procedures.)

BUCKWHEAT CAKES — BUCK-WHAT?

Buckwheat Cake Suppers are held regularly at churches, VFW halls, civic clubs or other social places in rural West Virginia. Every year, many attend the Preston County Buckwheat Festival in Kingwood, West Virginia. But how many know what buckwheat is and its history?

Buckwheat is a pseudocereal. This means that its name is deceiving in that it is not really a grain or wheat, and it is not even a grass.

Many buckwheat events originated during the late Great Depression. Buckwheat was seen as an “insurance crop” at the time because of its relatively short growing season. Farmers would come together at these events to celebrate the end of the growing season and their harvest. Those events survive today.

The family-operated mills that processed those buckwheat harvests were once a staple in West Virginia. Today, they’re nearly gone. However, there is hope.

In Avella, Pennsylvania, the tradition continues less than 10 miles from Wellsburg, West Virginia.

Weatherbury Farm grows and mills USDA certified organic grains. Today, they mill high quality certified organic flour including buckwheat flour milled from Westsylvanian Common Buckwheat. They also mill many other flours including wheat bread flours, Appalachian bread flour, pastry flour, rye flour, spelt flour, cornmeal and more. Like a fine wine, their “estate flours” are loved, chaperoned and defended from seed to field to flour without leaving their farm.

While the decline in the milling industry in the state forced citizens to purchase non-locally grown and produced products made with heritage grains, it also affected their social life. “A hundred years ago, every town had its own grist mill, which in addition to milling grains was also a community gathering place,” explained Nigel Tudor of Weatherbury Farm. “But then large roller mill operations replaced the local mill. And not only did the flours suffer, so did the community.”

PRESERVE THE PAST — FOR THE FUTURE

Without food traditions, future generations are robbed of the chance to understand a piece of who they are just like any other piece of their culture. Former television food personality Anthony Bourdain once said, “Food is everything we are. It’s an extension of nationalist feeling, ethnic feeling, your personal history, your province, your region, your tribe, your grandma.”

Without the preservation of our food culture, we become homogenized with a larger region and the rest of the country. It is the preservation efforts of so many, like the Vagabond Kitchen, Weatherbury Farm, Rising Creek Bakery and Café, and the Elkins Depot Welcome Centre, that are preserving that past for the future.

•Kyle Knox, born and raised in Marshall County, West Virginia, is a long-time events industry professional with years of experience working at various venues and events throughout the tri-state area, including The Capitol Theatre, WesBanco Arena, Jamboree In The Hills, Heritage Music BluesFest and the Wheeling Symphony. Before returning to the Wheeling area, Kyle also worked in the events industry in Pittsburgh. Kyle is passionate about music, Appalachian history and culture, nature and local sustainable foods. He is a 2013 graduate of West Liberty University and became a contributing writer for Weelunk in 2020.