That’s how Robert Driscoll describes designing and creating a machine called a gouger that makes oboe reeds, which is, in turn, made by an even bigger machine, a Haas CNC milling machine.

He will be playing the oboe — and playing with reeds he’s made himself — in the Wheeling Symphony Orchestra’s concert Thursday, Nov. 21.

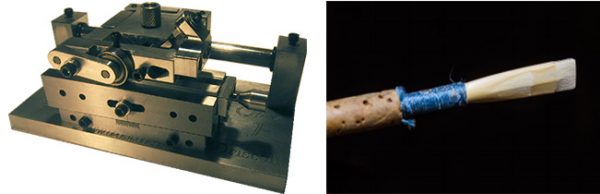

Driscoll holds a patent on the Opus 1 Gouging Machine, a machine that he designed and that he manufactures at his own workshop in Washington, Pennsylvania.

“It is basically a radial planing device that hollows out the bamboo material from which we fashion our reeds,” Driscoll said. You can read more about it at opus1gouger.com.

“Oboes use a cane reed to generate their unique sound,” Driscoll said. “This reed is made from two pieces of a bamboo material that is lashed together with thread onto a conical-shaped tube. The end of the bamboo is scraped thin so it can vibrate and make a sound.

“We make our own reeds, often one for each performance. By making our own reeds, we are able to tailor the sound of the oboe for the particular piece we are playing. Beethoven symphonies may require a big, substantial tone, while a Mozart symphony may demand a more facile, playful sound. The Françaix that I am playing for our concert is more like the latter.”

Driscoll’s a modern-day Pythagoras as far as I’m concerned. You remember learning the Pythagorean Theorem, that a2 + b2 = c2 for the sides of a right triangle. That same ancient Greek also defined a tuning system that was used by musicians for more than two millennia from his day in the 6th century BC into the 16th century.

Driscoll has taken a similar path. He studied math and music at Oberlin College and Case Western Reserve University; then, he got a master’s in performance at the Cleveland Institute of Music, but clearly he didn’t cast aside his slide rule at that point.

“I have been interested in making things since my youth. Today people like me are referred to as ‘makers.’ I was an early adopter here. Math was a natural interest for me,” Driscoll said.

“Math is pure in many respects and is a wonderful balance to studying music, which requires constant honing of skills. With math, when you understand a concept, you have it. With performing music, you have to keep your abilities sharp. Every day not moving forward feels like a step backward. It is like being a finely skilled athlete.”

The piece Driscoll will be featured in on Thursday night is like a finely tuned and well-pruned watch, Jean Françaix’s L’Horloge de Flore. The title connotes Flora’s Clock or The Flower Clock, and the piece draws inspiration from an idea set out by the Swedish botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus (1707–78).

Linnaeus spent decades in the field studying anything he could find animal, vegetable or mineral. In his 1751 work, Philosophia Botanica, he muses on the peculiar regularity with which some species of flowers open and close their petals at a certain time each day.

He proposed (as a thought exercise more so than a plan for any actual device or installation) a Horologium Florae — Flower Clock. Flowers would be set in a circle like a clock face, with each plant’s position corresponding to the hour it blooms. Then one could tell the time by observing which flower was open.

Françaix was a 20th-century French composer; L’Horloge de Flore was first performed in 1961. “Françaix is a favorite composer of woodwind players. His music is very colorful and flashy with many ‘jazzy’ sequences,” Driscoll said. The piece is “seven movements played without a pause” in which Françaix gives voice to various flowers on Linnaeus’ clock.

I. 3 a.m. Galant de Jour (poisonberry)

II. 5 a.m. Cupidone bleue (blue catanche)

III. 10 a.m. Cierge à grandes fleurs (torch thistle)

IV. 12 p.m. Nyctanthe du Malabar (Malabar jasmine)

V. 5 p.m. Belle de nuit (deadly nightshade)

VI. 7 p.m. Geranium triste (mourning geranium)

VII. 9 p.m. Silène noctiflore (night-flowering catchfly)

“Each movement takes on its own brilliant character and highlights the endless variety of color in the sound of the oboe,” Driscoll said.

Composers often strive to call forth the spirit of nature, as Françaix does here, or as Vaughan Williams does in The Lark Ascending, or Mahler in his Third Symphony. I probed Driscoll about what he as a musician tries to bring to light.

“Letting the music speak is really our only job on stage,” he said. “The music we have is like a blueprint into the mind of the composer. An architect looks at a two-dimensional drawing and can see a majestic building. We, as musicians, see dots on a page, and we have to make them sing.

“The nuance we bring to the music depends on our skills, but our main goal is to bring the music that the composers hear in their heads off the page and into the ears of the audience. That is a very important job. With composers as gifted as Sibelius and Mozart, for example, you can imagine how challenging that job can be.”

ROI MEZARE’S CLARINET CHALLENGE

Roi Mezare will take up this challenge, too, featured in the Mozart Clarinet Concerto. Mezare and Driscoll are fellow woodwind players and fellow principal members of the Wheeling Symphony. They are the reason that Thursday’s performance is being billed as “Hometown’s Finest.”

Bruce Wheeler, executive director, said, “I always am very proud when we feature our own musicians as guest artists on a concert. It shows the caliber of musicianship that makes up the Wheeling Symphony Orchestra.”

Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto is a gem of the repertoire. It shone for Mezare in his youth: “I first heard this concerto in my teens and remember the impressions it left with me,” he said. “I was, and still am, amazed at how beautiful and natural this composition is. I remember how the feeling grew inside of me wanting to share this music with the rest of the world.”

Mezare sprouted in a musical space. “My immediate family always liked music and appreciated it. In fact, my parents were the ones who introduced me to music and encouraged me to continue,” he said.

Mezare’s wider lineage was fertile musical ground as well: his great uncle was Paul Misraki, a film composer in Paris and Hollywood. Misraki worked in the music industry for six decades, scored more than 100 films, and collaborated with directors such as Jean Renoir, Jean-Luc Godard and Orson Welles.

Now a seasoned musician, Mezare is taking on a piece revered for its transcendent lines, a piece that has been essayed by fine players down the centuries.

I asked him how he, or anyone, dares such a performance. “The interpretive artist grows through his journey,” he said. “Over the years through studying and being exposed to different performing musicians, my concept evolved to where I am today. The general idea did not change, which is getting deep enough into the music to bring it to life. As if to bring the music out of the paper and recreate those emotions through my playing and then, in turn, share them with the listeners.”

The rarefied air of Mozart is sublime. So, too, is a good book on a brisk day. Outside the concert hall, Mezare enjoys reading things “that are far from everyday life and take you on a journey. Journey to Ixtlan by Carlos Castaneda fits that description.” And who could be a better reading companion than a foot-warming pup: “We have a 3-year-old Maltese, who my children named Happy.”

The program Thursday night also features Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture and Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1. Get there when the Geranium triste blooms, and you’ll have plenty of time to take your seat.

Tickets to “Hometown’s Finest: Mezare and Driscoll” can be purchased online at wheelingsymphony.com, by phone at 304-232-6191, via email at boxoffice@wheelingsymphony.com, or in person at the box office, located at 1025 Main St., Suite 811, Wheeling. Pre-concert dinner tickets ($30) can be reserved at 304-232-6191 or boxoffice@wheelingsymphony.com. Concert talk is at 6:30 p.m., and a reception follows the concert, both in The Capitol Theatre Ballroom. The concert will be conducted by John Devlin, music director.

• Ryan Norman hails from a suburb of Cleveland and earned an English degree at Wheeling Jesuit University. He lives in East Wheeling where you might find him listening to Gustav Mahler or Keith Jarrett, reading David Foster Wallace or Dave Eggers, and thinking along with Martin Heidegger and Roger Scruton. Ryan is also a chorister at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church and a member of The Prosers, a group that performs original poetry and prose at Towngate Theatre.