Editor’s note: In continuing coverage of Wheeling employment and business, Weelunk asked local historian David Javersak to put recent job losses in long-time perspective. For a specific examination of health care trends currently affecting area hospitals, check out Weelunk‘s earlier piece.

Sheep were once a thing in the greater Ohio Valley. A big thing.“This was basically the wool capital of America,” said David Javersak, Ph.D. and professor emeritus of history from West Liberty University.

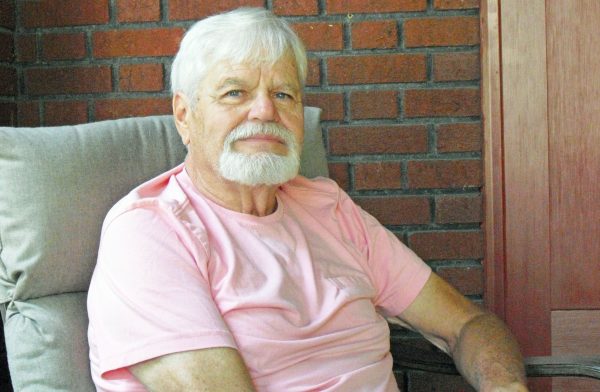

Javersak, who is in the middle of a public lecture series on labor in Wheeling’s 250-year history, made this comment to Weelunk.com while sharing a historical perspective on more than 1,000 proposed job losses in the city’s health care and academic sectors.

Yes, sheep were once a thing. Until they weren’t.

“We go from sheep to orchards in Hancock County,” Javersak said of statistics that show a sudden and rather mysterious switch.

He bolts from the comfort of a porch rocker and literally trots into his home. He returns with a whopper of a book that contains details of such local history as personal property records — by the district.

In one district of nearby Hancock County — he points out on a page where the type is so fine it’s nearly a gray blur — there were 20,421 sheep grazing on hillsides in 1864.

A little more than a decade later, the same district was down to 5,185 sheep. The pattern repeats elsewhere in that county. Another district dropped from 19,700 sheep to 3,400 in that time. Still, another fell from 13,000 sheep to 3,600.

What happened? Javersak still isn’t sure, but he knows precisely why the next rural wave of making a living — fruit orchards — fizzled. It was the railroad and an open door to nationwide shipping.

The orchards along the Ohio River were good, but, “we discovered in Washington (state) there was the perfect environment to grow fruit.”

By the early 1900s, the orchards that ran up and down the valley’s hillsides were disappearing. It was a similar pattern to what happened with grain.

“In the 19th century, there was wheat all over this place,” Javersak said, noting Wheeling’s massive industrialization was pretty much contained to the downtown, with agriculture just outside the city. “But, why bother when you can grow it in mass quantities in the Dakotas and put in in a rail car and mill it in Minneapolis?”

“I don’t think most people realize how delicate the balance is of things,” he added, linking the agricultural pattern to that of industry.

SMOKE STACKS AND COAL CARS

“Wheeling — in the 1920s you had 500 people who made a living somehow working with streetcars,” Javersak said of Wheeling’s peak industrial era, roughly 1830 to 1930. “So, we get rid of streetcars, and those people had to find other jobs.”

The tech of the day that killed the streetcars — personal automobiles — also ended the horse-and-carriage industry. When cars came in, the jobs of wagon makers, harness makers and those who operated livery stables went out, he said.

“It’s like a snowball in reverse,” he said of how quickly employment can unroll.

Same thing for metal production and the local need for coal to fire up the mill furnaces needed to make it.

“I grew up in Weirton, home of the mighty tin can,” Javersak said of the city that lured his family from Europe to the Ohio Valley.

For about two generations, the thin steel plates at the cores of those cans offered employment. His own father was among some 12,000 steelworkers, a job, that comparatively, Javersak said no longer exists locally.

At its industrial peak, Wheeling produced everything from body coolers (for the funeral industry) to beer to glass to steel to fabric to cut nails. It was an industrial hub, limited only by its location, Javersak said of how it compared to Pittsburgh, which had more room to expand.

Then came waves of change. Prohibition. The Great Depression. Wheeling’s 1937 flood. Plastic. Pressed-wood I beams. International shipping.

FAST CHANGE, SLOW CHANGE

Sometimes, Javersak said, employment sea changes have been rapid. Like the sheep or the streetcar workers. Other times, it brews, like the overall rise and fall of industry that Wheeling experienced.

Still other times, the brevity of human life makes it difficult to see that a change is even happening.

When Javersak runs the numbers, for example, he noted that Wheeling’s industrial era was weakening even when the city might have felt like a perpetual boom town.

He specifically compared the 1980s to the 1920s. In the 1980s, Wheeling lost 19 percent of its population — much of this due to job losses in the industrial sector. Javersak said age and gender charts, which are normally shaped like a pyramid, with fewer elderly people at the peak, suddenly looked like the letter “T.”

That loss was visible and felt by all, but the decline actually started decades before that, he said.

Looking way back at census records, he said Wheeling was seeing population upticks throughout its industrial peak, but not as big of upticks percentage-wise as some other cities. By 1920, the city would have seen its first-ever population decline if that hadn’t been the same time period when outlying areas were annexed, he explained.

By the 1930 census, population decline was showing up on the census and continued to do so. Right up to the big decline that anyone could notice in the 1980s.

“I don’t think we appreciate the kind of changes that occur and the impacts they can have,” he said of looking at how the economy flexes over time. “(Workers) always assume that what they can remember is what’s always been.”

COLLEGE JOBS

But, what about the jobs that require college education?

Javersak noted that professors, doctors, nurses and administrators are among those suddenly unemployed by dramatic downsizing at what is now Wheeling University and by the proposed closures of Ohio Valley Medical Center in Wheeling and East Ohio Regional Hospital just over the state line.

“There’s no sure thing,” Javersak said of everything from those nearly-proverbial sheep to, well, being a professor of history.

He said he entered academia in the 1960s, which turned out to be a good time. He began his tenure at West Liberty with a master’s degree and finished his Ph.D. while working — with a team of eight other historians. He said he couldn’t do that in today’s job market, which is flush with a glut of fully-degreed, wanna-be faculty and fewer jobs.

“You can’t absorb them all,” he said of younger historians. He both chuckles and involuntarily shudders. “I envision the day when … all American history will be taught by one guy and uploaded at universities all over the country … It’s so impersonal.”

But he notes the move to e-employment is marching on, personal or not. Add in the international element, population shifts and other tech changes and it’s hard to tell what will be the next “sheep” or “tin can.”

Robotics, in particular, is something he’s been studying. If international trends hold steady, he suspects even jobs such as bank tellers — far, far from manufacturing —- are not long for this world.

NEW OPPORTUNITIES

But that isn’t entirely a bad thing. He notes that with each employment loss, new opportunities have opened — like the orchards that followed the sheep, or the international, e-jobs that are now booming in Wheeling’s downtown.

And, oddly enough, history sometimes repeats itself.

He said he is old enough to have seen Wheeling swing back and forth on specific things, such as the state of the riverfront. Earlier in his life, it was a park. “In the 1960s, they took that out and put in a parking garage,” he said. “That was progress at the time.”

In the early 2000s, the parking garage was torn down and the ironically park-like Heritage Port was created. Alongside a civic center whose rejection a generation or so earlier Javersak links to a wave a downtown commercial decline. Which is also in reverse.

He suspects the trades will similarly recover, as, in America at least, we are producing fewer workers than there are jobs. At least for now.

Change may be the only constant, in fact.

“Just because you have a job now doesn’t mean you’ll be doing the same job in the future,” Javersak said of the need for pragmatic thinking and flexibility. “I don’t think there are any guarantees.”

WANT TO KNOW MORE

Readers who would like to hear more about the history of labor in Wheeling and its surrounds may enjoy lectures Javersak and Hal Gorby, Ph.D., are giving as part of the People’s University series at Ohio County Public Library. Classes, which are free and part of Wheeling’s 250th anniverary celebration, meet 7 p.m. on upcoming Tuesdays in the auditorium. Remaining topics include the 1931 Coal Strike on Aug. 20, the labor-organization legacy of the Reuther family on Aug. 27 and an exploration of Wheeling’s tobacco industry on Sept. 3.

• A long-time journalist, Nora Edinger also blogs at noraedinger.com and Facebook and writes books. Her Christian chick lit and faith-related non-fiction are available on Amazon. She lives in Wheeling, where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household.