To hear more about his long career, I paid a visit to Ralph and Janet Tomlinson at their home in Mozart.

GETTING STARTED

“I went to barber college back in ’67,” Ralph said. “I graduated two days before Christmas.” But although he had a diploma, he didn’t have his license yet and wasn’t sure what his next step would be. Fortunately, Ralph’s father, a longtime employee of Wheeling Steel, stepped in to offer his son some help and guidance.

“My dad heard about a barbershop up in the Laconia Building,” he remembered. “The barber wanted to sell, and my dad talked to him and said, ‘If you stay a year, I’ll buy the shop off you for my son.’” The barber agreed and stayed until Ralph could get his license. Ralph cut hair in the Laconia shop for a year and a half before moving down to 33rd Street, where he would spend the rest of his career.

LIFE ON 33rd STREET

Ralph’s shop was a tiny block building with a red roof, an awning and a barber pole. It’s still there. The property originally belonged to a barber named McGuffey who cut Ralph’s hair when Ralph was a kid. When he saw it, Ralph’s dad made an offer.

“My dad bought that shop, and I was there for 49 years,” he said. His dad bought the adjacent house too, where the McGuffeys had been living. The news, however, came as a bit of a surprise to Ralph’s mother. They’d been living in a home down the street for decades.

“[Dad] came home and said to Mom, ‘How’d you like to move?’” Ralph recalled. She was a good sport, and the family moved five rooms and a full basement into two rooms and a half-basement behind the barbershop. Ralph and his parents lived in those close quarters so Ralph could devote all his time to his business. His father insisted upon it.

“I opened up at 8 o’clock in the morning,” Ralph said. “There would be guys standing there, waiting for me to open. And I worked until 6 o’clock at night. I did that for five years because my dad said, ‘You get one day vacation for each year. Five years will be a week.’”

He remembered the ebb and flow of foot traffic. Between four and five in the afternoon, things would die down. Just before closing, though, the floodgates often opened. Ralph found himself working many days until eight o’clock at night. He didn’t want to turn anybody away while he was building his business. Indeed, it seems Ralph never turned anybody away, ever.

Nevertheless, he sometimes had a problem with loiterers and guys hanging around, so he’d announce, “Anybody wants a hair cut needs to put their money right there [on the counter].” The lurkers would disperse, leaving the serious customers to wait.

“That was the last time I put up with a bunch of boys coming in to kill time,” Ralph said, laughing.

I asked Ralph if he ever shaved his customers. He said he did at first, but very few wanted the service. He remembers practicing on his fellow barber college students.

Efficiency was the name of the game. He never had a partner or a student barber with him. It was just Ralph, all day, six days a week.

“I had six chairs. I’d cut in one, five would be waiting,” he said. “When I started, flattops were popular. I was the flattop guy. They’d say, ‘You want a flattop? Go to Ralph.’ Then after about 10 years, flattops went out of style.” He joked about kids in his own elementary years sporting bowl cuts.

FINDING TIME FOR LOVE

At the end of each long day on his feet, Ralph came home to his wife Janet.

“We got married in 1977,” she said. “I knew him a long time ago. I was married … but I always wanted to marry [Ralph]. And I always wished he’d never find anybody. He didn’t, and after my husband passed away, I married him.” After the wedding, Ralph moved out of the tiny house on 33rd Street and into Janet’s Mozart home. They’ve been together 42 years.

“I don’t know what she saw in me,” he chuckled. “I really don’t.” Janet works in the Elm Grove Plaza in the evenings, cleaning. It’s a job she inherited from her parents when they died. She remembers Wheeling as a busy place and noted that it’s no longer that way now. But she loves it and has spent all her life here.

Janet helped her husband recall some of the fuzzier details from decades past. She told me he was the third barber in the family, after his uncle and cousin. And the Tomlinsons are a perfectly matched pair, easy-going and devoted.

“He’s even-keeled,” she said. “He’s the same in the morning as when he goes to bed.”

IMMACULATE RECORDS

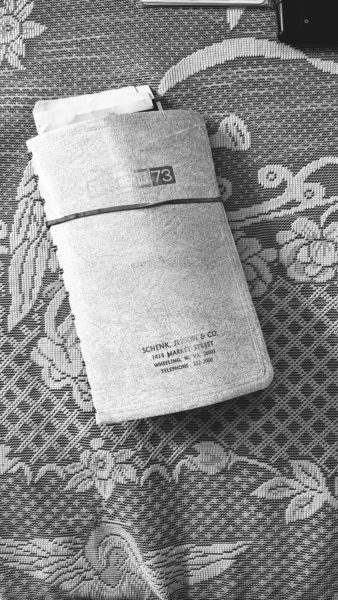

While I talked with Janet, Ralph dug out one of his old accounting books in his basement.

“I got all the old books. I wrote down everything,” he said. For 50 years, he wrote down dates and names and accounting details. When he got busy and didn’t have time to catch a customer’s name, he improvised with monikers like “New Pontiac Man” and “Man That Came Back.”

As he looked through the old books, it was obvious he was remembering his long years of work and the parade of faces that came through his door each week.

“I never thought I’d remember some of these things,” he told me.

When he began, Ralph charged $1 for a haircut. He said his union wanted to raise rates to $1.25, and a lot of barbers balked. Eventually, he charged $1.50. By the time he retired in 2018, a Ralph cut cost $12, and not every customer was thrilled with it.

“People didn’t want to pay,” he said. “Some would just walk out. If I had all the money that people owed me over the years, I would have approximately $5,000.”

People would say they’d pay Ralph later, or offer $10 when the cut cost $12. Still, he never threw anybody out, and often took what they offered because it was better than nothing.

HANGING UP HIS CLIPPERS

Business began to slowly dwindle in the late ’90s, but Ralph continued to cut hair through his 70s and 80s. He was ready to stop in 2015, but it took three more years for him to finally retire. There was just too much demand for his services from long-time customers. Apparently, in his absence this last year, they’ve found themselves adrift without a barber.

“There’s more than two or three fellows that I haven’t seen since I’ve quit. They haven’t gotten their hair cut because they want me to cut their hair,” he said.

He says he’s glad to be finished, though, because he doesn’t have to pay property taxes any longer. What’s more, he said men’s styles have changed. Younger people didn’t always like his haircuts. He implied that he might have kept going into his 94th year, but he simply didn’t have the business any longer.

“People let their hair grow, now,” he said. “They all have beards.”

LOOKING BACK ON 50 YEARS

“Would you do it again?” I asked Ralph of his five decades in the barbershop.

“I was ornery,” he said, leaving my question hanging. There was no doubt in my mind that Ralph was and is still ornery. Janet smiled.

He thought for a moment, and then said, “If I had to do it over again, I would. You had to be there in the shop. If you weren’t there, they’d go someplace else. But it was a good career for me.”

Then, he looked at his wife and added, “I don’t know how she puts up with me sometimes.”

• Laura Jackson Roberts is an environmental writer and humorist in Wheeling, West Virginia. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Chatham University and serves as the Northern Panhandle representative of West Virginia Writers. Her hobbies include hiking, travel and rescuing homeless dogs. Visit her at laurajacksonroberts.com.