By the spring of 1864, the tide of the Civil War favored the north. In March of 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was appointed general-in-chief of the Union Army. Grant’s strategy was to keep the pressure on the Confederates in both the east and the west thereby wearing down the enemy through a war of attrition. By then, the prisoner exchanges between the two sides had almost completely ended.

In history class, most of us learned that Grant had stopped the prisoner exchanges since the Union had access to more manpower, but those exchanges had already ceased by the time Grant took command. As the Confederate Army continued to shrink, so did the Union Army. In addition to losing men to battlefield casualties, the Union Army was losing men simply because their terms of enlistment were up and they were going home. As a result, Grant sent a plea for assistance to the northern governors asking them to activate some of their National Guard units to be assigned to routine low-risk duties like guarding railroad depots and other facilities to free up the more experienced soldiers to serve at the front lines.

In response to this call, Ohio Governor David Brough activated the Hardin and Licking County National Guard units and sent them to Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio.

The Licking County group consisted of six companies of men and the Hardin county unit consisted of three companies of men. Lieutenant Benjamin Allen Biggs was one of those men. Born in 1830, Benjamin Allen Biggs was the grandson of General Benjamin Biggs. General Benjamin Biggs served in Dunmore’s War, the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. He also served in the Virginia Legislature and was an early civic leader in West Liberty. Lieutenant Benjamin Allen Biggs and General Benjamin Biggs are both buried in the old West Liberty Cemetery

Governor Brough tasked Newark, Ohio resident, Colonel Andrew Legg, with the job of combining the National Guard units to form the 135th Ohio Infantry Regiment of the Union Army. The men were informed that their terms of enlistment were for 100 days and that they would have the very low-risk job of guarding the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. After the men spent a few days at Camp Chase picking up uniforms, equipment, and supplies, Colonel Legg swore them into the Union Army on the morning of May 11, 1864. A few hours after the men were mustered in, the 135th Ohio boarded a train for the Martinsburg, W.Va., region to begin guard duty along the B&O Railroad.

Legg assigned companies B and F, under the command of Captain Ulysses S. Westbrook, to guard the North Mountain Railroad Depot that was located just over a mile northeast of Hedgesville, W.Va., and about 10 miles north of Martinsburg. The detachment consisted of just under 200 men. With the exception of the little training that the National Guard had undergone a year earlier in response to the incursions into Ohio by Morgan’s Raiders, the men had very little training. To make matters worse, Captain Westbrook frequently drank heavily and was often too drunk to command effectively.

Located at the intersection of the B&O railroad tracks and what today is Hammonds Mill Road (Rt. 901), the North Mountain Depot installation consisted of a small depot building near the road and a small two-story blockhouse just east of the tracks a couple of hundred feet north of the depot. The original garrison had dug a shallow trench around the buildings. Just beyond the ditch, the original garrison had also created an abatis consisting of rows of fallen trees with sharpened branches to create an obstacle for any attacking forces. However, the abatis had large gaps where men had chopped up some of the trees for firewood during the previous winter. Since most of the fighting was taking place far from North Mountain, the men from the 135th didn’t bother to repair the damaged fortifications. Although they sent out patrols in the mornings and evenings, no enemy forces were spotted. Several times during the early summer, there were reports of Confederate troops in the area. The garrison went on alert, and patrols were sent to investigate, but all of those reports turned out to be false alarms. It appeared that the promise of a low-risk assignment was good, so the men were pretty complacent by mid-summer. Other units from the 135th were assigned similar duties along the Baltimore & Ohio railroad at Kearneysville, Van Clevesville and Opequan Station, with the overall headquarters being at Martinsburg.

In June of 1864, General Robert E. Lee ordered General Jubal Early to attack federal forces in the Shenandoah Valley to try to loosen Grant’s tightening noose around Richmond and Petersburg. Early’s advance guard included Brigadier General John McCausland’s cavalry brigade that consisted of over 1,300 men. McCausland’s men arrived in the vicinity of Hedgesville late on July 2, 1864. They immediately cut the telegraph lines and took control of the town with a tight grip to prevent anyone from alerting the men at North Mountain Depot. Although over 1,300 Confederate cavalrymen were encamped just over a mile away, Captain Westbrook and his men were completely unaware of their presence until the next morning when McCausland launched his attack. Most of the men later blamed Westbrook for this lack of information because he was very intoxicated that evening.

Early on the morning of July 3, 1864, McCausland’s men decamped and headed toward the North Mountain Depot. An early morning patrol crested a small rise and encountered some of McCausland’s men approaching from the east. One survivor of the Battle of North Mountain later told his daughter that it looked like the whole Confederate Army was coming toward them. The men from the 135th fired one volley at the approaching cavalrymen and then ran back to alert the others and to seek safety inside the fortifications at the depot. None of the Confederate soldiers were hit by the volley.

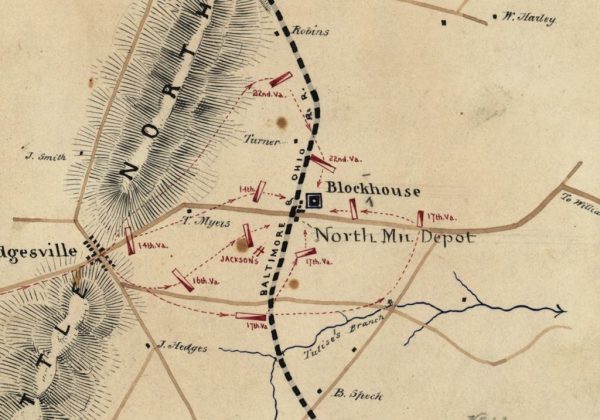

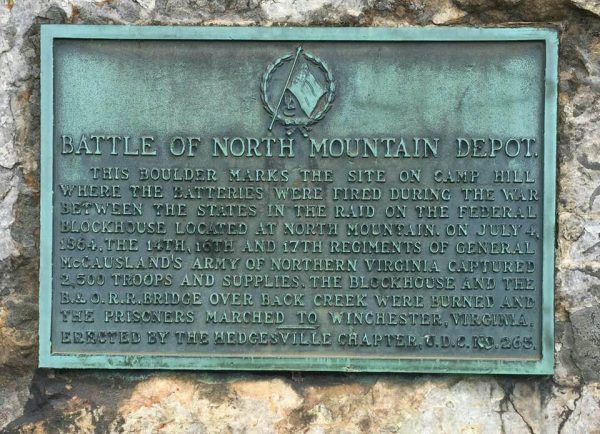

McCausland sent the 14th Virginia and the 16th Virginia to attack the depot and blockhouse from the west while ordering the 22nd Virginia to circle around to the north. In the meantime, the 17th Virginia was divided into two units with one attacking from the south and the other from the east. In short order, the vastly outnumbered men of the 135th Ohio were surrounded and under attack from all sides. They all quickly abandoned the shallow trenches and crowded into the two-story blockhouse. After a short firefight, General McCausland ordered his men to hold fire and dispatched a white flag detail to approach the blockhouse to demand that the defenders surrender. As the men carrying the white flag approached the blockhouse, Westbrook noticed that the Confederates were moving some light artillery pieces into position to attack the small fortress. Considering that action to be a violation of the spirit of the white flag, he ordered his men to open fire on the white flag detail causing the men in the detail to dive for cover. Although no one in the detail was hurt, McCausland ordered his men to resume the attack on the fort. The shooting continued for over two more hours. Then, Captain Jackson’s artillery battery, which had set up on a small hill about three-quarters of a mile away, found the range. Several balls struck the structure supporting the roof of the blockhouse causing part of it to collapse onto some of the defenders on the second floor. In addition, the front door of the blockhouse was almost destroyed. After three hours of furious gunfire on all sides and after the roof collapse, Westbrook finally realized the futility of his situation. If he did not surrender, his men would be annihilated by the overwhelming firepower of the Confederate forces, so he displayed the white flag and surrendered. Even though the battle lasted for three hours, only two men from the 135th had been killed and six wounded. Two of the wounded died a short time later. There are no reports of any of the men on the Confederate side being killed or wounded.

After the surrender, the Confederate soldiers burned the blockhouse and a nearby railroad bridge over Back Creek. Then, they stripped the men of the 135th of nearly all of their belongings including their boots since many of the cavalrymen were wearing worn out boots. However, one man was allowed to keep a small New Testament Bible that his mother had given to him. Then, the men were forced to march under the stifling July sun through the rugged hills almost 200 miles to Lynchburg, Va. One survivor said that the prisoners were given nothing to eat for the first four days of the march. A number of the men died due to exhaustion and dehydration during the march. At Lynchburg, the Confederates forced the prisoners to crowd into cattle cars to be transported by rail to Camp Sumter near Andersonville in Southern Georgia.

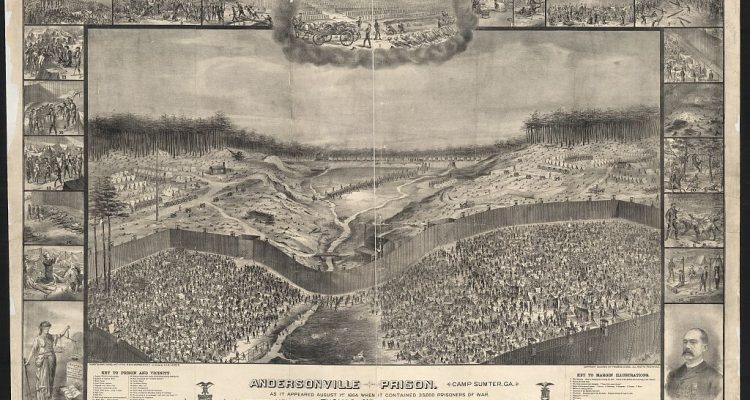

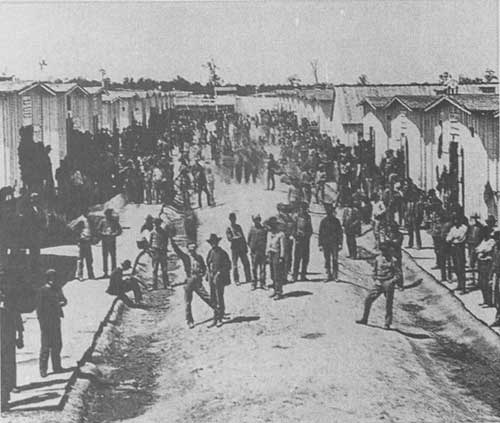

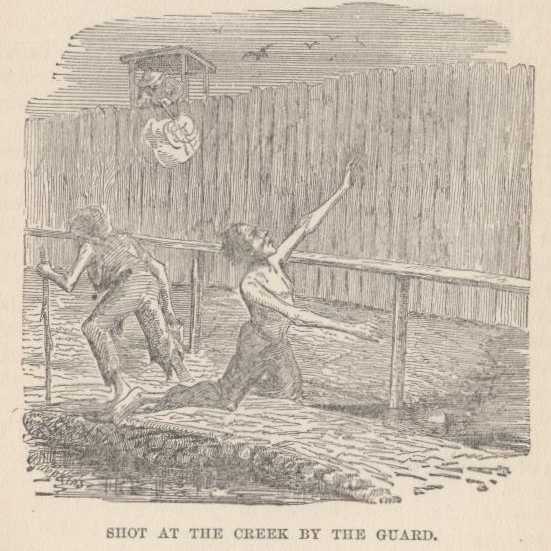

The cattle cars lacked sanitary facilities, and the guards provided no food and very little water to the prisoners during the long trip in the summer heat. The cars were so crowded that the men had to stand for most of the trip. Several more of the men died during the journey. At the time of their arrival at the Andersonville prison in late July 1864, it housed over 33,000 union prisoners, and men were dying at the rate of 100 per day. Although conditions at Civil War POW camps were deplorable on both sides, Camp Sumpter became the most infamous because of the inhumane conditions at the camp. After the prisoner exchange between the north and the south disintegrated in 1863, the Confederacy faced the problem of an ever-growing abundance of war prisoners. In response, they built Camp Sumpter near Andersonville, Ga., during the early winter of 1863-64. Camp Sumpter (AKA Andersonville Prison) consisted of an area of roughly 16.5 acres enclosed by 15-foot stockade walls that were 1,620 feet long and 779 feet wide. The deadline, which consisting of a single rail set atop a row of posts, was located 19 feet inside of the stockade walls. Guards were ordered to shoot to kill anyone who crossed the deadline. A swampy area through which a muddy stream flowed from west to east, divided the enclosure almost in half. The first prisoners arrived in February 1864.

By the time that the men from the 135th arrived, the prison population had grown to over 33,000 even though the camp was designed to hold only 10,000 prisoners. In his later recollections to his daughter, one of the survivors from the 135th described the prison. The horrific stench of the prison greeted the men before it even came into view. They disembarked from the train with those who were unable to walk being assisted by their comrades. The prison contained no sanitary facilities, so human waste covered much of the ground because many of the men were too weak to make it to the places that were used for such purposes. The swampy area and stream flowing through the camp formed an open sewer, flowing with human waste. Flies and maggots covered almost everything making the very ground underfoot appear to be alive. The men were assigned a small plot of ground. However, they had no tools or supplies with which to build shelters to shade them from the stifling summer sun. Thomas Elihu Hayes of the 135th had managed to keep a small penknife that he had hidden in a pants cuff when the cavalrymen searched him. In addition, he had a small New Testament Bible that his mother had given to him that the cavalrymen had permitted him to keep.

Hayes and a number of other prisoners joined together to read the Bible, pray and sing gospel songs. As more men joined in the worship group, they began to pray to God for some help. By August, the polluted stream flowing through the camp had started to dry up creating an even worse water crisis. On Aug. 3, 1864, the men in the Bible study began a community prayer vigil to ask God for water. The men decided to take turns praying in groups nonstop until God answered their prayers. On Aug. 8, the skies opened, and it started to rain. For the next five days, rain poured from the sky. As the storm grew more intense, many of the thirsty men in the camp laid down on the ground with their mouths wide open hoping to catch a drink. The rain continued unabated for five days unleashing a torrent of water that tore out a section of the western stockade wall and flowed through the camp washing away much of the filth that covered the ground. As the storm raged on the sixth day, Aug. 14, 1864, a spring erupted from the hillside on the western side between the stockade wall and the deadline. Some of the inmates reported that the spring appeared after a bolt of lightning had struck inside the compound. By tying a tin cup to a long pole, the men were able to just reach the spring to get a drink of clean water. Prompted by the Sisters of Mercy, the guards build an enclosure around the spring to contain the water and moved the deadline closer to allow the prisoners access to the new supply of clean drinking water. Considering the spring to be a miracle, the prisoners called it Providence Spring. Providence Spring continues to flow to this day.

One man recalled the severe infestation of lice in the prison. He said that a man could stand and remove every louse from his body, but would be covered again as soon as he sat or laid back down. Prisoners often went for days without eating. When the ration wagons finally appeared, they dispensed hard dry corncakes made from course-ground cornmeal or hard soda biscuits. Sometimes, the prisoners also received a small square of dried meat. After unloading their cargo of cornbread or biscuits, the ration wagons were piled high with the corpses of the men who had died. Heavily guarded prisoner details were taken out to bury the dead in mass graves.

The men of the 135th quickly learned to stick together to prevent the prison gangs from taking their meager rations or any other belongings. They had no eating or drinking utensils, and the men who were not already sick quickly fell sick from drinking the polluted water from the stream. Only one-third of the 200 men of the 135th who were taken prisoner at the North Mountain Depot survived and made it home.

The Camp Commandant was Captain Henry Wirz. He ran the camp with an iron fist, but by the end of the summer, he realized that something had to be done. In September, he paroled a small group of men with the condition that they would go to the northern commanders and entreat them to resume the prisoner exchange program. Even though he had not received a response from the north, Captain Wirz began paroling small numbers of prisoners including a handful from the 135th starting in October. In November 1864, another group of survivors from the 135th was paroled. According to the diary of Thomas Elihu Hayes, the men were taken to Polaski, Ga., where they were turned over to the Union Fleet on Nov. 26, 1864. Once they were aboard the ships, the sailors provided the men with new uniforms to replace the ragged uniforms that they had worn for the last six months. The sailors tossed the old uniforms overboard into the Atlantic. When he boarded the ship, Hayes still had his penknife and Old Testament along with a few small wood carvings that he had made during his captivity. He did not realize that those were in his old uniform pockets until it was too late. Hayes reported that the ship that he boarded was the USS Constitution, which took him to Annapolis, Md. The paroled men arrived at the U.S. Military Hospital at Annapolis on Dec. 1, 1864. After a brief period of recovery at the hospital, the men were transported back to Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio, where they were mustered out in January and February of 1865. Lieutenant Benjamin Allen Biggs of West Liberty and most of the other men from the 135th who were interred at Andersonville were paroled on April 28, 1865, at Lake City, Fla. Lieutenant Biggs was mustered out at Camp Chase in Columbus on June 22, 1865. When he was paroled, Lieutenant Biggs was suffering from severe chronic diarrhea that plagued him for the remainder of his life. It is worthwhile to note at this point that a few of the men from the 135th had been taken to other Confederate prison camps. Some of them survived, and some did not.

Unfortunately, we do not know a lot of details of the life of Benjamin Allen Biggs after the war. We know he was born on May 24, 1830, that he served in Company F of the 135th Ohio Infantry, that he married Mary A. Jones and that he passed away on July 18, 1900. He is buried in the Old West Liberty Cemetery. Perhaps someone reading this will be able to add a comment and contribute more details about his life.

Geohistory Coordinates

Below are the GPS Coordinates for some of the sites mentioned in this story for those who enjoy playing the Geo-History game. If you are unable to visit the sites in person, just copy the coordinates and paste them into the search box on Google Earth. Then, use the street view to see what the locations look like today.

Camp Chase and the Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio

Coordinates: 39°56’37.53″ N 83°04’33.53″ W

The historical marker for Camp Chase is on the north side of Broad Street just left of the entrance to the cemetery.

West Liberty Cemetery and the grave of Lieutenant Benjamin Allen Biggs

Coordinates: 40°10’03.51″ N 80°35’37.29″ W

No Street View Available

Site of North Mountain Depot and the Battle of North Mountain

Coordinates: 39°33’47.61″ N 77°58’49.05″ W

The Depot was on the south side of the road next to the tracks.

The large white house north of the road is about where the blockhouse was located.

Site of Battle of North Mountain Historical Marker at Hedgesville Middle School

Coordinates: 39°33’21.57″ N 77°59’28.95″ W

The stone holding the bronze historical marker plaque is on the lawn of the school just southeast of the road.

Camp Sumpter Historical Marker near Andersonville, Ga.

Coordinates: 32°11’44.30″ N 84°08’02.43″ W

Providence Spring and Providence Spring Historical Marker at Camp Sumpter near Andersonville, Ga.

Coordinates: 32°11’39.85″ N 84°07’49.03″ W

Source Materials

Here are some of the online source materials for this story for those of you who would like to do more research:

Web Page

135 Ohio Infantry

Compiled by Larry Stevens

Last updated Jan. 17, 2013

www.ohiocivilwar.com/cw135.html

Web Page

CIVIL WAR INDEX

135th Ohio Regiment Infantry

www.civilwarindex.com/armyoh/135th_oh_infantry.html

Copyright 2010 by CivilWarIndex.com

PDF Document

135th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry Roster of Troops

www.civilwarindex.com/armyoh/rosters/135th_oh_infantry_roster.pdf

Web Page

National Park Service

Andersonville Historic Site Web Page

www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/grant-and-the-prisoner-exchange.htm

Web Site

Library of Congress Maps

www.loc.gov/resource/g3881sm.gcwh0008/?sp=18

Map: Nos. 13-13a: North Mountain Depot, Virginia

Web Site

Ancestory.com record for Benjamin Allen Biggs

Web Site

National Park Service: Camp Chase

www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/civil_war_series/5/sec2.htm#1

• Earl Nicodemus is retired after 40 years of teaching Instructional Technology at West Liberty University. He helped to form the West Liberty Historical Society, and he and his family have taken care of the historic West Liberty Cemetery since 1985. He is particularly interested in folk stories about local historical figures and often gives presentations to community groups.