In this series, we’ll talk to locals who struggle with autoimmune disease and share their stories. Below, Ohio Valley residents Ashley Suder and Allison Stoner open up about their experiences with lupus.

What is Lupus?

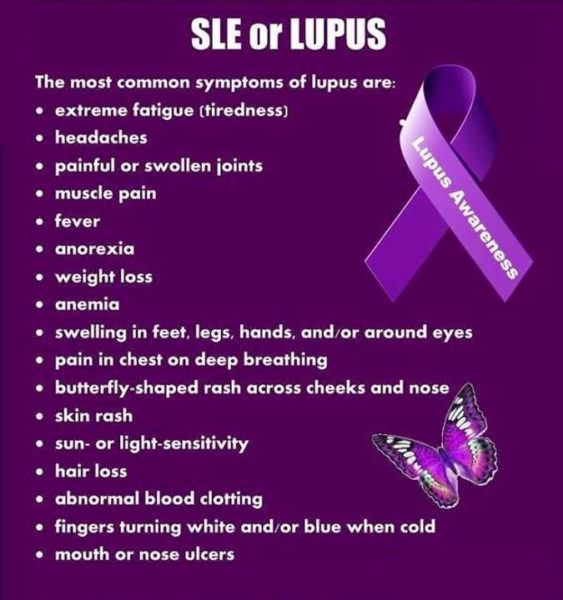

Lupus is incredibly difficult to explain, let alone diagnose. Most people have heard the nam e; far fewer understand what the disease entails. It’s a chronic autoimmune disease, a condition in which the immune system attacks the body by mistake. Roughly five million people around the world suffer from lupus. While the disease takes myriad forms, the inflammation it causes can affect almost any part of the body: skin, joints, connective tissues and organs. The most distinctive sign of lupus is a butterfly-shaped rash on the face, but the rash often travels all over the body, and not all patients will experience a skin condition. Many patients are sun-sensitive and develop skin lesions after exposure. With symptoms like severe fatigue, fever, joint pain, chest pain, digestive issues, organ failure and confusion, it’s no wonder lupus is so cruel and so hard to diagnose. The disease is more common in women between ages 15 and 45, and it’s also more prevalent in African-Americans, Hispanics and Asian-Americans.

e; far fewer understand what the disease entails. It’s a chronic autoimmune disease, a condition in which the immune system attacks the body by mistake. Roughly five million people around the world suffer from lupus. While the disease takes myriad forms, the inflammation it causes can affect almost any part of the body: skin, joints, connective tissues and organs. The most distinctive sign of lupus is a butterfly-shaped rash on the face, but the rash often travels all over the body, and not all patients will experience a skin condition. Many patients are sun-sensitive and develop skin lesions after exposure. With symptoms like severe fatigue, fever, joint pain, chest pain, digestive issues, organ failure and confusion, it’s no wonder lupus is so cruel and so hard to diagnose. The disease is more common in women between ages 15 and 45, and it’s also more prevalent in African-Americans, Hispanics and Asian-Americans.

Ashley Suder and Allison Stoner are both living with lupus here in the Ohio Valley. Both in their early 30s, their cases present quite differently, as lupus usually does.

How Did It Begin?

“My whole life, I’ve never felt good,” Ashley Suder said from under the safety of an umbrella. Her body can’t tolerate sun exposure. She’s had symptoms of lupus since she was young: chest pain, joint pain and digestive issues, among others. Being in the sun makes it worse.

“As a child,” she said, “the doctors were like, ‘She’s stressed. She’s just basically a neurotic child.’” After high school, her symptoms got worse. Different doctors gave her different diagnoses.

“Nobody listened. Nobody believed me,” she said.

She went on to college, where she felt constantly anxious and stressed. Things continued to decline for Ashley in mortuary school in 2009. Though that had been her lifelong dream, her symptoms progressed and interfered with her schooling. Her hair began to fall out, and she fell asleep in class. After graduation, she began an apprenticeship at a local mortuary, where stress, along with sun exposure while parking cars and walking in the cemetery, wreaked havoc on her body. Ultimately, she had to quit and give up on her dream.

By contrast, Allison Stoner led a normal, healthy life as a mother and occupational therapist. It wasn’t until a few days before the birth of her second daughter that she noticed two small red spots on her nose, like those left by a pair of sunglasses.

“I delivered her,” Allison said, “and it went into a full-blown rash all over my face. Then it got really itchy, and then it spread symmetrically. It blew up to my whole face, went down my neck and chest, down my back, down my arms, down my trunk, down my legs, down my hands. It was like having poison ivy times one-thousand, 24/7.” She went to a dermatologist, a decision she now regrets. He told her she was hormonal after childbirth and that her rash was dermatitis. He prescribed creams and steroids, repeatedly, for several months. But something told Allison it was more than just a hormonal reaction.

“I’m an educated person,” she said. “I work in healthcare, so I felt like something was missing. I went back and said, ‘Something doesn’t feel right. I don’t think it’s just my hormones. He swore to me for months and months and months that it was. After time, my hair started falling out, my joints started hurting. I started having lots and lots of signs of lupus.”

Both Ashley and Allison experienced what most autoimmune patients do: a lengthy period of suffering punctuated by doctors who either didn’t listen or didn’t see the signs. It takes the average patient three years to receive an autoimmune diagnosis. Often, it takes far longer.

Getting Diagnosed

A UPMC internist suspected Ashley had a connective tissue disease and sent her to the rheumatology department, where she finally tested positive for lupus. Since then, she’s found a rheumatologist who works at Yale. He’s been a valuable resource, she said, because lupus is so tricky to diagnose.

“That’s the hardest thing to explain,” she said. “Anything can be involved. A lot of people tend to think it’s just joint pain and rashes and your hair falling out. Having sun sensitivity. And for a lot of people, that’s all it is. But then there’s those of us with a lot of organ involvement. One of my biggest symptoms is GI dysmotility. I have gastroparesis and intestinal dysmotility. I’ve had two pulmonary embolisms, two DVTs (deep vein thrombosis). I have some level of heart involvement, a couple leaky valves. The arthritis — I have a hard time moving around. I have a lot of CNS, like central nervous system involvement. That’s been my other really big problem. I’ve tried all the medications there are.” Fortunately, her Yale doctor supports her, and this can make all the difference. For so many autoimmune sufferers, feeling heard is an essential part of coping.

Allison, too, had to wade through many misdiagnoses before she got her answers. Though her dermatologist continued to insist she was suffering from dermatitis, she decided to take her health care into her own hands.

“I requested my own bloodwork and my own biopsy of my skin,” she said. That was in October 2013, and, unfortunately, the results of her tests got lost. By Christmas, she couldn’t hold a pencil or open a bottle of water. Finally, she got confirmation. It was lupus.

Allison went to the Lupus Clinic at UPMC where she was put on several strong medications, but they made her feel worse.

“I felt like I was dying from the inside out,” she said of the drugs’ side effects. “The [doctor’s] answer was ‘Let’s give you more.’ My answer was, ‘You’re not the right doctor for me.’ I found Dr. Jellan in Elm Grove. He’s an MD, but he practices holistic medicine. He listened.” Dr. Jellan went over her history in detail and determined she has over 35 food allergies in addition to lupus. Newer ones continue to develop. He also told Allison to stop taking the potent drugs if she didn’t think they were helping. So she did. Now, she’s totally prescription-free. Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean she’s symptom- or pain-free.

How Lupus Affects Their Lives

How do Ashley and Allison cope with lupus?

“In the short term,” Ashley said. “I just try to live day by day because I never know exactly how I’m going to feel. I can wake up sometimes and be like, okay, I can sort of move, it’s gonna be a good day. Then, like today, I’m in so much pain. I was in tears just washing my hair. And long-term? I just trust that somewhere, somehow, a more effective medication will come out, and maybe one day I’ll feel better.”

Pain control is a big part of lupus, and that’s a difficult subject right now. When it comes to pain management, local facilities tell Ashley she’s too complicated, and Pittsburgh doctors don’t want to take West Virginia Medicaid. So, she treats her often severe pain with over-the-counter medication and exercise.

“My mom and I try to walk a mile every day,” she said. “And I do CrossFit at a very, very, very tamed-down level.” She also gives herself IV nutrition through a central line three times a week, along with one day of hydration.

Allison, too, finds that lupus complicates her life both professionally and personally. Being an occupational therapist does help, in terms of medical knowledge.

“I know how to strengthen my joints,” she said. “I know how to do weight-bearing or strengthening to try to keep joint mobility and keep things moving. I do have to watch lifting patients because my hands hurt. The grip strength is weaker than it used to be. I know my limitations. If it’s causing me pain, it’s not safe for me or the patient.”

As a parent, Allison said it’s affected her ten-fold. She’s deeply upset by the way her health interferes with motherhood.

“There’s not a day I don’t feel sick,” she said. “But what other choice do I have? I definitely feel like it’s a struggle trying to maintain composure when you feel like your body is attacking itself all the time, but you have other people that rely on you.” Most days, Allison is up at 5 a.m. for work, and shifts gears at 2 p.m. when her kids are finished with school. She does CrossFit and yoga and said the latter helps with joint pain. In addition, confronting her multiple food allergies has calmed her lupus symptoms significantly.

“Right now, I just deal with it. I choose to stay prescription-free as long as I can.” Her kidneys, liver, and blood cell counts are perfect.

“My doctor says, ‘Whatever you’re doing, keep doing that.’ The lupus is why I exercise, why I do yoga, why I see a counselor, just to have someone to talk to and give me some strategies that I can use.”

What They’ve Learned

Ashley Suder has more on her plate than most 30-year-olds. Nevertheless, she’s pursuing a career in nursing and hopes to work in a Level 1 Trauma center.

Ashley Suder has more on her plate than most 30-year-olds. Nevertheless, she’s pursuing a career in nursing and hopes to work in a Level 1 Trauma center.

Of the lessons she’s learned, she said, “I can push through anything. If I can survive all that stuff, well, simple things don’t bother me anymore. I never thought I’d find another career that I would want to do as much as being a mortician. I actually went to Israel this summer for the third time. And when I went in 2013, I was like, ‘I’ll never be able to go back.’” But she did. She had the blessing of all her doctors, who helped her plan for the medical care she’d need on the trip.

“I had two giant medical suitcases,” she said. “But I did it. And I ended up in the ER there. But, I still did it. You gotta do it while you can. And that’s another thing I want people to realize. I still want to live my life. I still am allowed to do fun things that you don’t think are advisable.”

Allison Stoner has learned to be her own advocate. She knows it’s important to find the right doctor.

Of her physician, Dr. Jellan, Allison said, “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have any idea I have all those food allergies. Part of the journey is finding a doctor that looks at the big picture and listens to what you’re saying.”

She adds that doctors treat symptoms individually; they may put patients on antidepressants for pain and creams for rashes without seeing the whole disease. Because lupus can look so different from person to person, and tends to be misdiagnosed, she’s vocal about her diagnosis.

“I feel like there’s not a lot of people that know the signs or the symptoms,” she said. “Or they just don’t even know what lupus is. Because I started becoming open, a friend who was having symptoms reached out to me.” She helped that friend get a lupus diagnosis, and now they support one another.

Final Thoughts

You don’t look sick.

Both Ashley and Allison have heard that phrase again and again. Usually, it comes from well-meaning people who don’t understand that autoimmune disease does so much of its damage on the inside, and it can be hard to recognize at a glance. Pain is invisible. Moreover, most people with autoimmune disease try hard to mask their struggles, preferring to smile through it rather than complain. The most important part of living with lupus is finding physical and emotional support. By sharing their stories, they hope to shed light on this complicated condition.

Author’s note: If you would like to connect with other local autoimmune sufferers, find the Ohio Valley Autoimmune Support Group on Facebook. My deepest thanks to Ashley and Allison for sharing their stories with me and for their honesty and bravery. I’m honored to have met you both. If you have an autoimmune story and would like to share, please email Phyllis Sigal at Phyllis.Sigal@weelunk.com.

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.