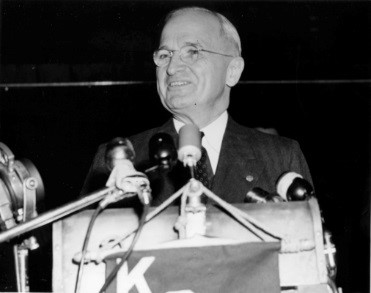

Harry S. Truman concluded his business at the front desk of Wheeling’s McLure Hotel, turned quickly to depart, and bumped forcefully into 36-year-old George Griffith. Both men were startled by the sudden contact, but George’s surprise was, by far, more dramatic. The last thing he expected was to smack head-on into the 33rd President of the United States on a rainy June 21, 1953.

“Excuse me young man,” the ex-President said. “Didn’t see you standing there.”

“No sir, Mr. President, I mean Mr. ex-Presi…I mean Mr. Truman…er…ah..,” George awkwardly replied while suppressing the urge to offer a military salute.

“That’ll do, son,” Truman said, shaking George’s hand. “Thank you for all your hard work with the Postal Service. Mrs. Truman and I appreciate all the work you fellas do to keep us connected with the world.”

George had forgotten that he was in his mail carrier uniform. The only reason he was in the McLure that morning was to deliver a parcel early for an ill colleague before heading on to his regular mail route in Elm Grove. He smiled and nodded at the retired politician’s compliment.

As for the ex-president, he was in Wheeling as part of a cross-country drive he was taking with Mrs. Truman. They were headed for New York City, where he was to deliver a speech. It was just he, Bess, and their shiny big black Chrysler New Yorker. There were no secret service men accompanying media caravan or staff. It could never happen that way in the 21st century, but it happened in 1953. The Trumans spent the night at the McLure and were due in Washington, D.C., later that day.

“Maybe you can do me a favor, son,” Truman said. “Mrs. Truman and I would positively love to visit a monument we have heard about for years that’s dedicated to Henry Clay. You wouldn’t by any chance know where that is, would you?”

George knew where most of it used to be because it was on his usual mail route in Elm Grove.

“Yes sir,” he replied. “It is right on Rt. 40 in Elm Grove just after you pass over the old stone bridge and the road takes a sharp left. It is on your right in front of an old mansion they call Monument Place, but it is owned by the Shriners now. I’m afraid there’s not much left of the monument. It’s really just a pile of stones now.”

“Well, thank you, son,” Truman replied. “That’s a shame. A real shame. This country just isn’t taking care of its history like it should. We will watch for it as we drive by. Excuse me now, but this young man from the newspaper wants to chat for a moment.”

Truman, in his brisk way, walked quickly across the McLure lobby to a man in a dark suit and a worn fedora—the very stereotype of an old time newspaper man—and shook hands. George wandered over to listen in. Word always seemed to leak out when the famous couple arrived in towns along the way, but Truman never turned reporters away.

This reporter’s name was Dent Williams, and he wrote for the Wheeling Intelligencer. Williams’ back was to George, and he talked very softly so George couldn’t quite make out the questions, but he sure could hear the answers from Harry Truman. He did hear the reporter mention Eisenhower and Korea and guessed that Truman was being quizzed about the ongoing conflict.

Truman declined to offer an opinion “because any comment I would make would be a half-baked comment, and Lord knows, I’ve had too many of those half-baked comments.”

A few moments later, he clearly heard Truman take one of his well-known swipes at Congress for not keeping up with the needs of the nation’s infrastructure.

“Wheeling needs a floodwall badly,” he said, “and I’m sorry to learn that construction funds were stricken from the federal budget.”

The interview turned to his trip, and Truman talked about how well his Chrysler was handling the challenge. He said his biggest regret was that he couldn’t travel without being recognized.

“I’ve found that it’s impossible to travel cross-country unnoticed,” George heard him say in concluding his lobby interview with Williams.

Mrs. Truman stepped off the elevator and George watched as she joined the ex-president and the couple walked into the coffee shop for breakfast. He couldn’t help but think about how much his late father-in-law, Tom Minns, would have relished hearing about his little McLure House adventure.

The McLure was no novice at playing host to famous politicians, entertainers, and military leaders since its opening in 1852. This wasn’t even Truman’s first visit. He had stayed there before as a Missouri Senator. During the Civil War, the hotel hosted General John C. Fremont, a renowned western explorer and the first presidential candidate of the anti-slavery Republican Party. Other Union Generals who hung their hats and spurs at the McLure were Generals William Tecumseh Sherman before his “march to the sea,” Ulysses S. Grant, before becoming the 18th President of the U.S., and William Rosecrans, the inventor, coal company executive and diplomat, before his devastating defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga. Presidential guests included Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, and, after Truman’s visit, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon.

And, Wheeling was no stranger to making national political headlines in the 1950s. Before Truman’s visit, there was Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s famous “I have a list” speech delivered at the McLure in 1950 and covered by Wheeling reporter Frank Desmond. He also covered the equally famous meeting of Eisenhower and Nixon at Wheeling’s Stifel Airport on Sept. 25, 1952 when the then-presidential candidate Eisenhower told then-Senator Nixon that he would keep him on the ticket as candidate for vice president in spite of Nixon’s recent dust up over the disposition of expense account funds related to campaigning. Nixon’s “Checkers Speech” cleared the matter up to Eisenhower’s satisfaction and led to the Wheeling meeting.

George headed back to work with a story to tell. Harry and Bess headed on to Washington, D.C., where they stayed in the elegant Mayflower Hotel and Harry held court with former colleagues in the U.S. Capitol. Eventually, they ended up in New York City, where they stayed at the famed Waldorf Astoria and Harry gave a speech to the Reserve Officers Convention.

In his speech, he spoke his mind about President Eisenhower’s plan to cut the military budget by 12 percent to pay for proposed tax cuts. Apparently, many in the president’s party believed atomic bombs were enough to keep the Soviet Union in check. Truman, on the other hand, believed that the U.S. needed to project strength with a strong military in addition to A bombs. He thought the president was sacrificing national security for tax cuts.

Unlike his late father-in-law, George really didn’t follow politics much. He was much more concerned with moving his wife, Mabel, toddler son, Terry, and mother-in-law, Lizzie, into the new house they purchased on Columbia Avenue in Elm Grove.

Read more about Harry and Bess Truman’s road trip in Harry Truman’s Excellent Adventure, the True Story of a Great American Road Trip by Matthew Algeo.