Elm Grove was a welcoming neighborhood for Mabel, George, Lizzie, and little Terry in 1953. The cozy little house on Columbia Avenue had something for everyone, and it was where the little family finally recovered from the loss of Tom. But, it would also be where Mabel would face the greatest, most staggering challenge of her life.

Mabel loved the cute little kitchen that had a restaurant-like booth and table in one corner, which were big enough to accommodate the whole family for meals and serve as a workspace for Lizzie’s telemarketing activities during weekday afternoons. She also loved the roomy dining room with the glass-fronted built-in china closet, and even the questionable over-the-fireplace black-and-white mural depicting some sort of Blue Marlin-like birds wading through a pond full of lily pads.

Lizzie loved the fact that once the furniture was set in permanent position, the house was easy for her to navigate in her blindness. She insisted on taking one of the two small upstairs bedrooms and leaving the larger first-floor bedroom for George and Mabel. She said using the steps would be good exercise, and before long she traversed them unwinded and with an easy glide.

Terry loved having many more kids to play with on quiet streets, and he particularly relished secret playtime down on the forbidden banks of Big Wheeling Creek just at the end of the street. He also had his very own bedroom (for now). School was just a short walk up Columbia to Kruger Street School.

George loved the space in the basement where he could set up the his first-ever workshop, tackle his own little projects, and wind down from his days as a mail carrier. The basement was also big enough to store the brooms, mops and other inventory for Lizzie’s telemarketing business.

They settled in. Before long, Mabel announced that another baby was on the way. Dr. Earl delivered that baby on Oct. 18, 1954, and they named him Gerry. Two weeks later, Mabel noticed a swelling, tenderness, and feverish touch in the baby’s left knee. Dr. Earl said he had picked up an infection, most likely in the hospital, and diagnosed osteomyelitis—a rare but serious condition that would require years of X-rays, treatment, and invasive procedures that would leave the baby physically scarred and disadvantaged for the rest of his life. It was stressful for the little family with the possibility of amputation hovering over the baby’s future if the infection couldn’t be defeated.

George doubled up on his attempts at stress relief, smoking more and putting more time in his big Christmas project in the basement workshop. He built a big heavy platform for under the Christmas tree that would accommodate Terry’s electric train and a variety of decorations that George carved out of wood and painted.

By Christmas Eve, the baby was home, recovering, and resting comfortably. Terry, as most 7-year-olds are, was anxious for festivities to begin. George finished his project and lugged, tugged, and forced the huge platform out of the basement for placement under the tree in a corner of the living room. The family gathered around to trim the tree, but George had to take a pass on that traditional activity. He said he wasn’t feeling well. He had a fever, and his arms, particularly his left arm, were painful. Eventually, he went to bed early.

George participated in Christmas morning gift opening but returned to his bed, listless and groggy. After remaining in bed for another day, it was time to call Dr. Earl. The family physician had a solemn look when he left the little first floor bedroom.

“I believe George has had a pretty severe heart attack,” Dr. Earl explained in his deep, soft, comforting voice. “I think we need to call an ambulance to take him to the hospital where we can get him oxygen and make him more comfortable.”

As the uniformed ambulance attendants brought George through the living room on a stretcher, the mailman asked them to stop for a moment. He reached out to grasp Terry’s hand.

“You are the man of the house for a while, young man,” he said. “Take good care of everything.”

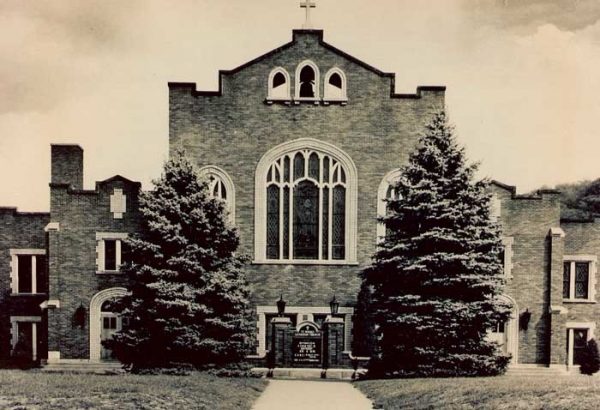

For the next three days, gracious neighbors and friends from church dutifully drove Mabel, who never learned to drive, to Ohio Valley General Hospital to see George. In 1954, there was little to be done for heart attack victims beyond close monitoring and the provision of oxygen.

George drifted in and out of consciousness under an oxygen tent and held Mabel’s hand through the ordeal. That’s what Mabel was doing alone in the plain white hospital room on Jan. 1, 1955 when George’s grip on her hand abruptly stopped and his breathing ceased. The 38-year-old who had survived a hard-scrabble childhood and youth, the hard work of the CCC camps, and the brutal conditions and labor of World War II in the Aleutians was gone after having finally led his family to prosperity and comfort.

Terry remembers the next-door neighbor making an appearance at the house where he remained with his grandmother and infant brother just before the telephone call came from the hospital with the news. Apparently, someone thought it would be better if Terry and Lizzie were not alone when they learned of George’s death.

“I don’t remember exactly what I heard, but I got the idea,” he recalled. “That’s when I knew life would be very different from that second on. I also realized the responsibility that Dad put on my 7-year-old shoulders with the last words I ever heard him say. I was determined to be as much of an adult about it as I could.”

Mabel couldn’t drive the family’s massive Nash, and the baby still required constant care, so she decided to have George’s viewing in the house on Columbia Avenue—an unusual but not unheard-of practice. Men from church rearranged the furniture to accommodate the casket that the experts from Altmeyer Funeral Home wrestled through the narrow front door. The women set up tables of food in the spruced-up basement, and the day of sadness seemed to drag on to those who stayed for the duration. The house, which remained filled to capacity with out-of-town family and friends from the old South and Center Wheeling neighborhoods, took on the sweet smell of the many flowers that arrived throughout the day.

“I remember the casket being in the living room while I tried to sleep exactly over it in the room upstairs that night,” Terry remembered. “That’s when I realized the mortality of everyone, including me.”

After George’s funeral and burial in Greenwood Cemetery, Mabel had to think about the rocky future her drastically altered family faced. She was responsible for two young children, one requiring ongoing medical care; an aging, sightless mother; a mortgaged house that needed upkeep; a drastically reduced income; and a big old car she couldn’t drive. She didn’t have much time to grieve.

First up was conquering the intimidating monster automobile. Determined not to be at the transportation mercy of others, she drew on the help of a number of old friends to take her out for instruction and practice sessions on Peters Run Road and through Oglebay Park. Soon, she had her license and felt comfortable enough to take the car grocery shopping, to the baby’s doctor appointments, and, eventually, to the Wednesday afternoon delivery runs for Lizzie’s business. She even worked up the courage to drive to Pittsburgh over pre-Interstate highways to restock inventory.

Except for serving as Lizzie’s eyes when they were out of the house, Mabel didn’t need to worry about her mother. In fact, Lizzie became an active second parent to the two boys although she never relinquished the grandparent right to spoil them with money and homemade treats whenever possible.

Mabel untangled the financial challenges by prudent disposition of George’s insurance policy and by arranging to receive his Social Security and “Letter carrier” benefits. Along with the money they made from Lizzie’s business, she figured they could just make it, if they were frugal and made wise decisions.

Mabel kept her grief out of sight as much as possible, but often wept at night when the rest of the family slept. Losing Tom and then George just two years later was a harsh blow to the little Wheeling family, but perseverance was the key to survival. And Mabel was determined that her family would be survivors. Although they didn’t have much money, her two boys would grow up never feeling like it. She and Lizzie would make for them as bright a future as possible.