T.J. Minns and his “Pal”

By Gerry Griffith

Weelunk Contributor

When my grandfather, Thomas J. Minns, had a full head of steam on the sidewalks of South Wheeling in the second two decades of the 20th Century, the best advice for pedestrians was to get out of the way. The short blind Irishman didn’t let sightlessness hamper his travels when he was focused on a destination.

A detailed knowledge of every street’s obstacles and character, a monster-sized helping of positive attitude, and the practiced and effective side-to-side tapping action of his bamboo cane along the uneven brick sidewalks allowed him to rocket to his destinations at a pace that would present difficulties for most walkers to match. He had places to be and errands to run.

Dressed in his typical white shirt, paisley tie with gold tie clip, wool pants, oversized topcoat, and well-worn fedora, Tom was on a mission one bright but cold day in November 1932. His trek over the brick sidewalks of South Wheeling was typically interrupted with frequent greetings from the folks along the way who were his customers as well as friends.

“Morning Tom,” offered the police officer on his beat as the little man sped by on his way uptown from the little confectionary he ran with his wife, Lizzie, who was also blind.

“I’ll be by for my paper later today,” said the butcher up the street sweeping the sidewalk in front of his shop.

“Tell Jimmy to stay put till I come by the store to pick him up after school,” called out a woman who was one of the several parents in the neighborhood who was in the habit of using Tom’s store as an after-school rendezvous point.

Tom acknowledged every comment and greeting with a smile, a nod and sometimes a hearty laugh, but he never slowed down. He was proud, resourceful, and fearless.

Today, he was on his way to the Wheeling Post Office, all the way up on Chapline Street, to mail a stack of letters that he and Lizzie had composed the night before. They used some very special but simple equipment and a skill they learned at the West Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind at Romney to keep in touch with sightless classmates and former teachers.

Their writing required a wooden slab about the size of a standard piece of paper that had notched holes in the right and left margins, a flat metal horizontal grid about two inches tall with prongs on either end that allowed it to fit into the holes of the wooden slab and over card stock thick, cream-colored paper, and a metal stylus that was used to punch a series of bump-producing indentations on the paper. Arranging those bumps into patterns that represented letters and words on the paper, the blind writers could compose written communication for consumption by blind readers. The final product could be read by sightless people using their elevated sense of touch and running their fingers over the series of arranged bumps on each page.

Most people would identify the technique as “Braille,” but Romney graduates used an altogether different system in the late 19th Century simply known as “print” that incorporated a whole other configuration of bumps to compose words and sentences. “Braille” readers couldn’t decipher “print,” and “print” readers would be just as baffled by “Braille.” It was blind consumers’ version of Beta vs. VHS; Apple vs. Windows; or PlayStation vs. Xbox.

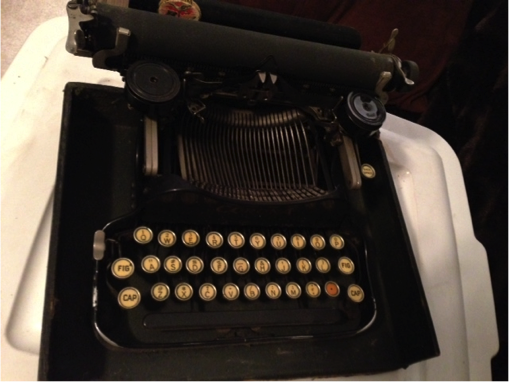

For communicating by letter with sighted friends and businesses, Lizzie used a worn little typewriter that she kept under their bed in an old beat up black case. She learned to type at Romney and remained a proficient typist and letter writer well into the 1960s. Customers of the series of little stores that the couple ran throughout South Wheeling could often hear the deliberate clacking and pecking of the little typewriter coming from the back room where Tom and Lizzie lived. She wrote to her family in Buckhannon, the insurance company in Columbus, the candy supplier in Pittsburgh, and she wrote to the parents of several blind children she had taught in Ohio and in Southern West Virginia before joining Tom in Wheeling.

Tom made good time on his trek from Jacob Street in South Wheeling with his packet of letters tucked inside his big, oversize topcoat. He was on Market Street between 16th and 15th streets when it happened. Like most busy cities of some size, Wheeling’s downtown stores received supplies through openings in the sidewalks with elevators that descended into tunnels that led to basement storage areas. The openings were covered with big iron doors that pedestrians walked over every day when they were closed, and they were supposed to be closed during regular business hours when folks were out and about. For one reason or another, one store on this particular day had not yet closed its sidewalk elevator doors and the open-sided steel slab elevator itself was on the basement level. Tom used his little cane to detect obstacles and steps that went up, not sudden deep man-made canyons in the sidewalk. At his speed, he never stood a chance, and he tumbled into the open sidewalk and into the metal abyss.

Fellow pedestrians quickly rushed to the open iron pit to peer down at what they expected to be an ugly sight. What they saw was plucky Tom Minns, apparently unhurt except for a mild conk on the head, feeling around with his hands for his Fedora and bamboo cane that he had dropped mid fall.

“Good God man, are you all right?” asked a postman who had been walking by on his route as the store manager brought the elevator up to street level and Tom was guided off the pad by several onlookers.

“Is that you Murphy?” Tom asked, recognizing the voice. “Could you take these letters and put them in post like a good man? Come by the store later, and I’ll treat you to a bottle of pop.”

The postman complied, and Tom, his morning’s mission complete, headed back down Market Street at the same accelerated pace with only the slightest limp—cheerful, proud and fearless as always.

News traveled fast in South Wheeling. The next day, visitors arrived at the store with a special present for Tom. They were an older South Wheeling couple who had befriended the Minns family and helped out from time-to-time when needed. They had heard about Tom’s incident the day before and had a then-unique idea. They brought Tom a scrappy little dog from the county pound and suggested that the little fella just might be helpful on his travels throughout the city.

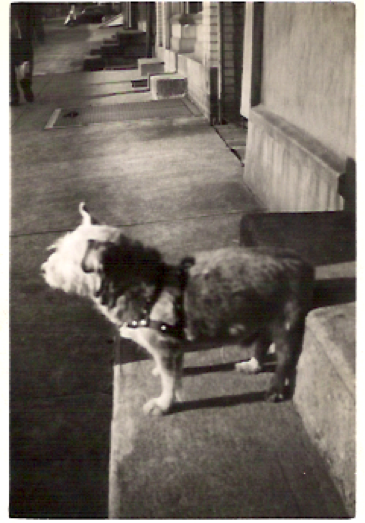

Tom was ambivalent. Lizzie was convinced it was a bad idea. She wasn’t a big fan of animals. Mabel, their teenage daughter (and my mother) was naturally enthusiastic. Tom’s reluctance melted away when the little mutt planted himself in his lap and didn’t move for an hour. Pal had already started forming a surprisingly strong bond to the active blind storekeeper in the strange way that dogs have of sensing when and how to be helpful to people who need them.

Tom named the little dog “Pal.” From that day forward, Pal accompanied Tom on all his travels. Although neither Tom nor Pal had received the kind training that today’s guide dogs and handlers now get, they quickly became a natural team with Pal leading the way on a long leash and alerting Tom of upcoming obstacles with a noisy little yap—the only warning Tom needed to slow his pace and use his cane to detect the problem. The odd pair became a common sight on the streets of South Wheeling.

Unfortunately for the rest of the family, Pal was a picky canine with loads of bad attitude. His loyalty was with Tom and no one else. Soon, that was understood, and Pal was pretty much left alone by Mabel, who at first wanted to dress him up in dolls’ clothing, and Lizzie, who just wanted him to stay away from her anyway. Pal was a cranky, yappy, hairy little mutt, but there was no mistaking the love and devotion that he and Tom shared. Pal was a member of the family for more than 10 years. They had many adventures that took them from the streets of South Wheeling to the city’s busy stogie factory floors and hundreds of spots in between. But, those adventures are other stories in the Mabel files. Oh, and Tom never fell into an open pit in the sidewalk again.

Previous Mabel Files: