By Gerry Griffith

Weelunk Contributor

The Mabel Files Part 5: Stogies, Sandwiches, and Crocheted Lace

The 1920s and 1930s were tough times for Tom and Lizzie Minns, the blind proprietors of a series of little confectionary stores in South Wheeling. They had Mabel, their little daughter, to take care of and a slew of well-meaning family members who questioned whether they could make enough money and raise a child without help.

The situation called for some clever action, an enthusiastic dose of hard work, and a few deals with some old friends.

In the late 1920s, Tom’s plan to put a few extra much-needed dollars in the Minns family operating account would require the cooperation of well-placed ex-“loafers”—young men who used to spend their evenings loitering about Tom’s series of South Wheeling stores. Some of those friends now worked in Wheeling’s most prominent companies — companies like The John Wenzel Meat Packing Company, the Strohman Bakery, and stogie makers M. Marsh and Sons, and the Pollack Stogie Corporation. Meanwhile, Lizzie had plans that would put her own surprising set of skills to work for the family.

Lizzie was an incredible baker and the creator of the kinds of intricate crochet work that would perplex the most talented of sighted experts in the field. She learned to bake, with her sisters, from her mother in the old family farm kitchen in Buckhannon, W.Va. Dinner rolls, pie, and cookies came out of the back room of the Minns’ confectionary on a regular basis and kept pleasant aromas wafting in the air of the little store most afternoons. Her big glass jars with tin screw-off lids, in which she kept sugar, baking powder, and baking soda, were labeled with Braille-like codes that she read with her fingertips so she could tell one ingredient from another. Those jars are still on my kitchen shelf today with the unique labels intact, more than 80 years after she affixed them.

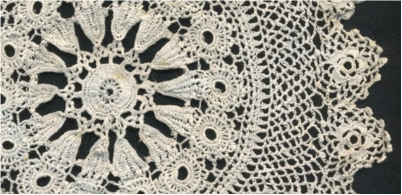

The ability to delicately craft the decorative lace that she created by hand with a small crochet needle and thin colored thread is more difficult to explain. Crocheting, like knitting, consists of pulling loops of string material through other loops and wrapping it around the hook one or more times. Crochet differs from knitting in that a single crochet hook is used instead of two knitting needles.

How Lizzie acquired such an intricate skill as a blind person is little understood, even by her family. Mabel explains that Lizzie learned the craft while attending the Romney School for the Blind and Deaf from a classmate, who was also blind. Sighted people have trouble understanding how the teaching and learning process must have worked. How do you learn such a seemingly difficult motor skill activity without reading about it or seeing it demonstrated? How would the teacher convey a lesson without being able to demonstrate it to someone who could see it? The transfer of knowledge about the craft from one blind person to another must have required an incredible proficiency in verbal description by the teacher; an above average comprehension ability by the student; hundreds of hours of practice; and, finally, appreciation of the final product by a sighted person.

Lizzie’s work took the form of beautiful furniture doilies, lace for incorporation into dresses, and, most prominently in my home for the next 80 years, lace trim on bed sheets and pillowcases. (The lace on my bed linens was often difficult to explain when I went away to college with the sheets and pillowcases that Lizzie had adorned with her intricate but sturdy lace augmentations so many years earlier).

Lizzie created her baked goods and crochet items for sale in the store and for incorporation into Tom’s entrepreneurial plan.

Tom crafted his money-making idea to take advantage of a captive Wheeling-based clientele — the men who rolled stogies in two of the world’s leading stogie factories and appreciated the convenience of having lunch delivered to them every day.

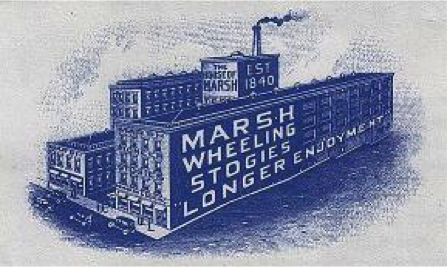

Stogies are like cigars but longer and thinner and made of different blends of cigar leaf. While stogies were invented in the city of Washington, Pa., Wheeling became a hotbed of stogie manufacturing. It is estimated that there were once more than 100 stogie factories in Wheeling that pumped out more than 6 million stogies a year. Eventually, there were two that dominated the industry — Marsh Wheeling Stogies and the Augustus Pollack Crown Stogie Factory.

In the 1930s, mechanized rolling machines came into favor, but in the late 1920s, stogies were still hand-rolled by skilled men who worked at marble-topped tables in large halls. Before radios became common, the rollers hired readers to stand on a platform and read aloud to them from newspapers and magazines. The men worked by the piece, so time was valuable. It was said that a good roller could produce up to 1,000 stogies a day. Time away from the rolling tables for lunch meant fewer stogies in production. Tom figured they would enthusiastically welcome a sandwich and a miniature fruit pie made by Lizzie if they could be delivered on time every day.

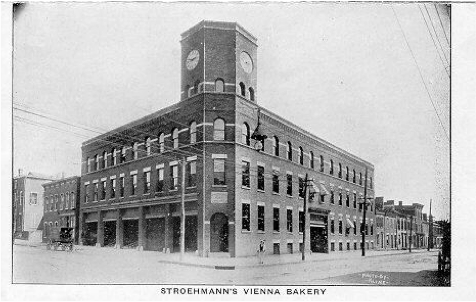

He needed a few things to make the plan work: good prices for bread and meat; permission to access the rolling rooms at Marsh and Pollack; and a way to transport the lunches to the consumer. Fortunately, as usual, he had friends in the right places. He visited one young manager at Stroehmann’s Vienna Bakery at 2204 Main Street who had been a “loafer” in the Minns Confectionary 10 years before. Tom cut a deal to pick up day-old unsold loaves of bread every day at a side entrance to the impressive bakery building at a drastically reduced rate.

Next, Tom visited another young manager, this time at the Wenzel Meat Packing Company at 4317 Wood St. The manager had once played on a baseball team that Tom sponsored.

Tom negotiated a great wholesale price for quantities of ham and beef, also to be picked up daily. Fortunately, the Wenzel Company was also a major producer of ice (50 tons a day according to a Wheeling Chamber of Commerce report in 1931). Tom got another handshake agreement to get enough ice to keep his products fresh.

Tom’s next visit was to both the Marsh and Pollock factory managers’ offices where he sought permission to access the rolling rooms by making a case for bringing lunch to the rollers to keep production levels elevated. Permission was granted.

Tom dispatched several of his current loafers to bring him lumber and wheels from a local junkyard. He built his own pushcart that he would use to transport meat, ice, and bread back to Lizzie’s kitchen. For several hours every evening, the little Minns family worked to cook the meat inside a large blue enamel “waterless” cooker, slice bread, make sandwiches with the meat, and then wrap the products in wax paper and pack them with ice and some of Lizzie’s baked goods in Tom’s transport cart. Every morning at about 10 a.m., Tom would put a leash on his little dog, Pal, grab his hat and cane and, when she wasn’t in school, enlist Mabel to walk with him North to the stogie factories.

In the rolling rooms of the factories, Tom wheeled his cart up and down the rows of rollers, shouting, “Who needs lunch? Who needs lunch? Pies and sandwiches. Pies and sandwiches.” Tom also carried a little box that held a supply of Lizzie’s crocheted items for sale. The stogie rollers would buy them as presents for their wives’ birthdays or for Christmas. Mabel helped carry the goods to the rollers who raised their hands and collected money and made change.

By 12:30, Tom, Mabel and Pal were headed south with their little cart for stops at the bakery and the meat packers to pick up supplies for tomorrow’s lunches. Then, it was back home to handle the on-rush of after school/after work store loafers.

Like many folks in Wheeling during lean years, the Minns Family used their skills and talents to get by as best they could. They survived without financial assistance from friends or family, and that was a victory they treasured for decades to come. Tom’s survival success was built upon ingenuity, a gigantic personality that bred loyalty among the army of young people who passed through his humble little confectionaries, and a belief in providing a good product for a good price.

More Mabel Files: