George Griffith hurriedly shoved the unopened, official-looking envelope into the breast pocket of his U.S. Postal Service uniform jacket, as he left the letter carriers’ locker room at Wheeling’s main post office on Chapline Street on an early summer afternoon in 1948. He was used to getting policy announcements and other bureaucratic notices of minimal interest in his employee mailbox. They usually ended up in the kitchen trash can once he got home and emptied his pockets. He figured this paper was no different. He was wrong.

It turned out to be his first brush with something that the news people on the radio were beginning to call the “red scare.” It wouldn’t be his last experience with the issue. A brash U.S. Senator from Wisconsin named McCarthy would see to that two years later when he would make Wheeling ground zero in his hunt for communists in the federal government.

“George, did you read this?” his wife Mabel asked that evening when she emptied his pockets at the kitchen table and opened the envelope.

“Nope,” he answered. “I figured it was just more junk from somebody who didn’t have anything better to do today than clutter up my mailbox.”

“Well, this says you are to meet with someone on something called the Loyalty Board next week,” she said. “Know anything about that?”

“First I’ve heard of it,” George replied.

Tom Minns entered the kitchen carrying his ten-month-old grandson, Terry. Tom was the family’s authority on everything from family finances to current events. He was a keen observer of society through radio news programs and Braille versions of news magazines that he voraciously consumed.

“Honestly George, you and Mabel really need to keep up with what’s happening around you just a little,” Tom said with a smile as he handed Terry to Mabel. “You know that ever since the end of the war, the Soviet Union has been trying to get its own bomb and tensions are high in Europe about what they have in mind. There’s been a lot of criticism of the Truman Administration with some folks saying he and the other Democrats are soft on communism, and he’s let a lot of communists work inside the federal government. He let loose with an executive order

last March that he hopes will put an end to all that.”

Tom explained to George and Mabel that Truman’s executive order established a series of “loyalty boards” to conduct interviews and investigations of every corner of the federal government to determine if there were employees who have been affiliated with communist organizations. The U.S. Postal Service was not exempt. The FBI used a long list of organizations it believed had associations with communism or the Soviets. If a name appeared on membership lists that corresponded to an employee name in the federal government, inquiries were instituted.

“You dabbled in any communist organizations, George?” Tom asked with a chuckle.

“You know I haven’t, Pap,” George answered.

“Then you have nothing to worry about,” Tom said. “Just go to the meeting, answer the questions, and everything will be fine. To my way of thinking, this is just another example of politicians trying to use fear to sway public opinion to their way of thinking. They scare people about foreigners and people of different religions and politics and whip them up to the point where there is so much suspicion and hatred that somebody has to do something to show they are taking action. I guess the actions that could be taken could be worse.”

A week later, George sat nervously in a conference room on the second floor of the Post Office Building across from an equally nervous inquisitor representing the Loyalty Board for the Postal Service. It didn’t take long to determine that someone by the last name of Griffith had been involved with an organization called the American League Against War and Fascism back in the 1930s. It was a group formed by the Communist Party USA and involved pacifists united by concerns over Nazism. The organization’s name appeared on the U.S. Attorney General’s list of groups considered controlled by subversive front organizations. So when the name Griffith appeared on its membership rolls and on the list of postal service employees, the Loyalty Board was dispatched to investigate. The Griffith in question, however, was not named George and he didn’t live in Wheeling. To George’s relief, the interview ended quickly and all uneasiness was relieved. George had never even heard of the American League Against War and Fascism. His loyalty was affirmed.

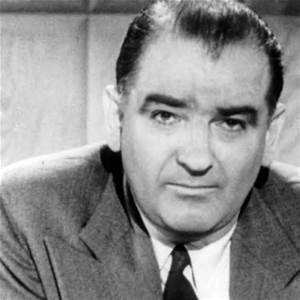

All was quiet on the red scare front in Wheeling until February 9, 1950. That’s when the Junior Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy, unleashed an infamous renewal of the issue with a speech at Wheeling’s McLure Hotel as part of the Lincoln Day Celebration of the Ohio County Republican Women’s Club. George Griffith didn’t attend that speech, but he had a close encounter with its author moments before.

George was still in uniform when he pulled his Hudson into the gas station on North River Road near Warwood on the afternoon of February 9. He had a habit of getting out of the car to chat with the attendant who filled the tank, checked the oil, and cleaned the windshield. That day was no different. He was talking football with the attendant when a big black Chrysler pulled up to the pumps next to George’s hulking old Hudson. George glanced into the back seat of the Chrysler and recognized former Congressman Francis J. Love who had just announced that he would try to recapture his First District Congressional seat in the fall elections. But, there was a stranger sitting in the seat next to Love. He was middle aged, on the heavy side and his hair was thinning on top. What was left of it came to a point on his forehead. He wore a rumpled suit. He was scribbling furiously on a yellow notepad and gesturing with his free hand. Love nodded in reaction to whatever his companion was saying.

When the Chrysler’s tank was full, the driver floored the accelerator and it jumped away from the station in a spray of gravel and dirt.

“Those fellas were in a hurry,” George observed to the attendant.

“Yep,” he man responded. “That there was a U.S. Senator from Wisconsin, according to the driver. They just landed up at the Ohio County Airport. I guess he is giving some kind of speech tonight at the McLure to the Republican Women. Don’t know what some Wisconsin politician could have of interest to say to West Virginians. We will probably never know.”

He was wrong. The whole country would know Wheeling as the launching pad for three years’ worth of McCarthy self-promotion, blustering and intimidation of thousands of Americans that came in the form of McCarthy’s “I have a list of names” speech. George had just been in the right place at the right time to see Joseph McCarthy moments before he unleashed what would become known as McCarthyism—seen as the fight for America by some, and a witch hunt by others.

Two hours after George saw McCarthy, the Senator was escorted to the podium at the McLure Hotel where he began the talk that would reverberate around the country for months. Read the text of his speech here.

The next day, Mabel read Frank Desmond’s story about the speech in the Wheeling Intelligencer out loud to Tom and Lizzie.

“Good grief,” Tom said when she finished. “This is going to cause a commotion. I just hope he has proof of what he is saying. This is going to scare the daylights out of people. I bet Wheeling is going to have one more thing to be famous for once this story circulates.”

While he never made his alleged list of communists in the State Department public, McCarthy’s speech seemed to have more of an impact on regions far from where he delivered his initial attack on Truman and the Democrats for being soft on communism. The Democratic Party did maintain control of both houses in the Presidential mid-term elections but lost 28 seats and strengthened a conservative coalition that kept Truman’s policies from passing.

If McCarthy intended his Wheeling talk to “scare some sense” into voters in the First Congressional District, he must have been disappointed. In that race, the Republican incumbent, Francis Love, who escorted McCarthy from the airport to the McLure for where the famous speech was delivered, lost his bid to return to Congress. Love was a graduate of Bethany College and former principal of Warwood High School. Democrat Robert L. Ramsay, a WVU graduate and a practicing lawyer from Brooke County who was a son of a coal miner, defeated him.