A Pioneer Woman

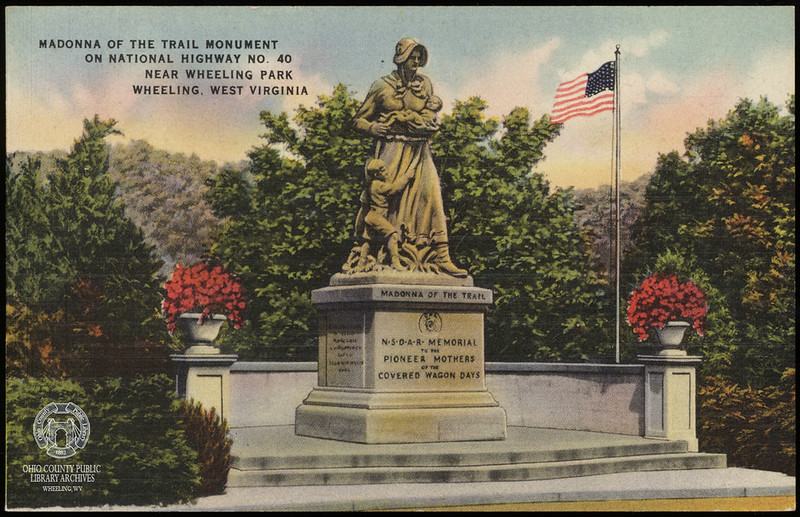

The “Madonna of the Trail” statue on the edge of Wheeling Park along Route 40 is hard to miss. It has become an icon in Wheeling and has been featured prominently on everything from welcome signs to tourism brochures.

The sculpture itself depicts a 10-foot tall, 19th century era, pioneer woman, holding a rifle in one hand and cradling an infant in the other with a young boy clutching her skirts. Her features are stern, almost traditionally masculine, and she is stepping forward boldly—as if into her future in the West.

But…most people don’t realize that Wheeling’s Madonna isn’t the only statue of its kind. There are twelve—all across the United States.

Many Madonnas

In the early 20th century, the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) and the newly-created National Old Trails Road Association (NOTR) teamed up to designate and commemorate the National Old Trails Road. The commemorative road system stretches from Maryland to California and is largely made up of the National Road (Route 40) and the Santa Fe Trail. After the Industrial Revolution, travel by automobile was becoming more popular and accessible in the early 1900s, spurring a sense of nostalgia for the old trails and migration by covered wagon.1

In honor of the American women—pioneer women—who traveled west and built new lives along these trails, NSDAR and NOTR commissioned sculptor August Leimbach to create twelve identical Madonna of the Trial statues, one for each state the National Old Trails Road passed through. All of the statues were made out of a cost-effective algonite and installed between 1928 and 1929, each costing $1,000.2

Amazingly, all of the Madonna statues still exist. Some have been moved due to sinkholes, road expansion, or other construction. Although the Madonnas were all intended to be identical, due to age and a variety of different restoration times and materials, the statues now vary in color. Many originally thought that the statues should face West, symbolically representing the pioneers’ journey, however, only four Madonnas ended up facing that direction—Wheeling included.3 Today, some of the Madonnas of the Trial stand in prominent, well-frequented locations, while others have become somewhat obscured, sandwiched next to fast-food joints. Wheeling’s Madonna has remained in its original location, yet still retains its roadside prominence and attraction.

Wheeling’s Madonna

When it came time to choose the host town/city for West Virginia’s Madonna of the Trail statue—the choice was pretty simple. Since the National Road only passes through a very small section of West Virginia in Ohio County, Wheeling was the clear choice.4 Wheeling was also the western terminus of the National Road for several years before it was expanded into Ohio. Constructed between 1811 and 1834, the National Road (Route 40) was the first federally funded road that was created to access western territories; it reached Wheeling in 1818.5 Thousands of covered wagons and stagecoaches carried people, goods, and mail along the famous thoroughfare, including many Americans looking to start new lives and futures.

In addition to the requirement that the statue be located along the National Old Trails route (National Road), another criteria was that the location was (or near) a site of historical significance. Wheeling Park was a public space that was easily accessible and popular with Wheeling residents. It was also right down the road from the Shepherd Plantation—a site that has long played a role in the lore of National Road.

The Wheeling Madonna was the second of the twelve statues to be erected; it was dedicated on July 7, 1928 in front of a reported 5,000 people.6 It was only preceded by the statue in Springfield, Ohio by a mere three days.

The ceremonies included speeches, religious invocations and benedictions, salutes, and patriotic songs. Otto Schneck, the chairman of the Wheeling Park Commission, accepted the monument from the NSDAR and NOTR on behalf of the city.7 The addresses were printed in the Wheeling Daily News for those who missed the event. The statue was described at the time as “a fitting memorial to the pioneer women” and a “worthy gift to be cherished as a zealous treasure.”8

In some ways, Wheeling was short-changed. Harry Truman, who would eventually become the 33rd U.S. President, had traveled to Wheeling to give a speech at the monument dedication as the president of NOTR. However, before the ceremony, he was called away back to Kansas City, Missouri where he served as a county judge and missed the Wheeling festivities. Truman wasn’t the only guest of honor absent—Mrs. Albert J. Brosseau, the president of the NSDAR, was unable to travel due to a sprained ankle.9

Over eight decades later, Wheeling’s statue was restored in 2012 using granite dust from the same Missouri quarry that Leimbach got his original materials to make the Madonnas.10 From where it still stands at the entrance of Wheeling Park, the Madonna of the Trail statue has ushered people into Wheeling for almost a century.

A Complicated Commemoration

We all remember watching old Western television, like Bonanza, and hearing stories of Lewis and Clark, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, and others. Our imaginations ran wild with games like “cowboys and Indians” on the playground or the computer game, The Oregon Trail. But thinking back…who were the stories about and who was telling them? Who was supposed to be the “good guy” and who was always the “bad guy”? Are women portrayed as independent figures or were they cast as supporting characters to the rugged men conquering the West?

So then, having a monument to the pioneer women, who were just as crucial to building the American West, is important…right? While women in general are underrepresented in our country’s vast collection of monuments, statues, and memorials…the Madonna of the Trail statues present their own set of historical problems.

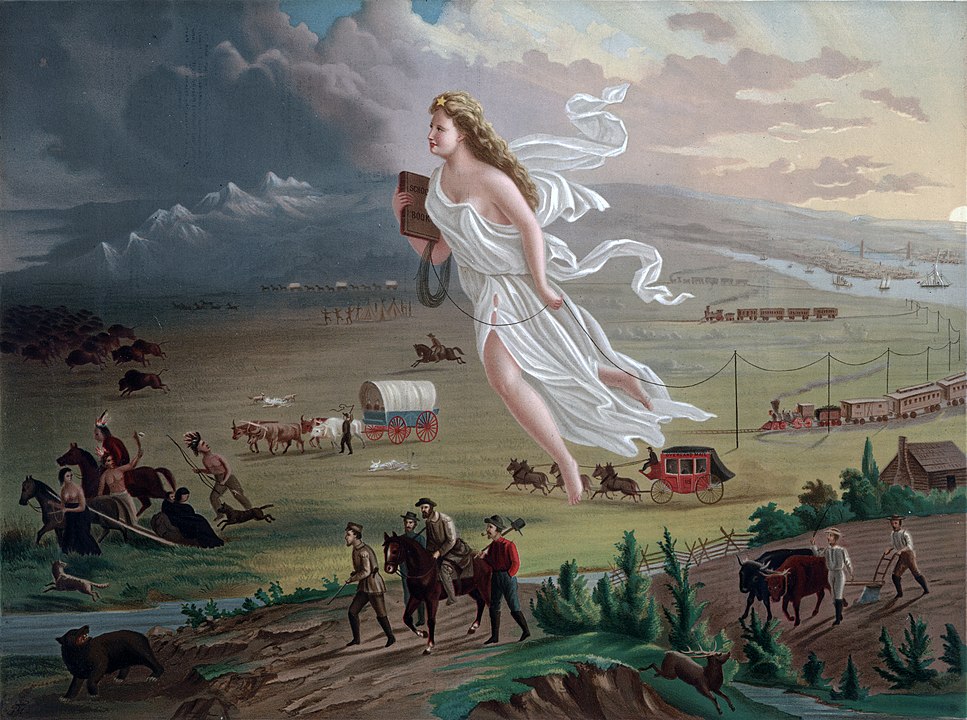

The Madonna of the Trail statues are part of a larger movement of pioneer monuments installed across the United States throughout most of the 20th century to “celebrate” the success of (white) settlement across the American West. In the 19th century, there was a popular belief that white Americans were destined to conquer the West, called “Manifest Destiny.” The U.S. Government used this idea to encourage Americans to move and settle west, on land that was forcibly taken from indigenous peoples. The remaining pioneer monuments that exist all across the country continue to glorify a white-washed history of westward expansion.

These pioneer monuments range from depicting overt white supremacy with inclusions of an indigenous “savage” cowering beneath a white man to the subtler Madonna of the Trail. According to Dr. Cynthia Culver Prescott, Associate Professor of History at the University of North Dakota, “these statues still represent a racist view, ignoring the cost of white settlement on Native lands. Like earlier monuments, they reinforce white dominance and erase ethnic diversity in the American West.”11 For some, these pioneer monuments, including the Madonnas, remind them of their nostalgic sense of the old West; for others, the statues remind them of their ancestors’ pain and the parts of their history that were lost.

White women have long been used and manipulated as symbols to justify the American settlement of the West—they are on monuments, part of paintings, in books, and more. However, they are almost always depicted as a mother figure, part of a family, or some other supporting role. What kind of message does this send about the value of these women? In these symbols, women are rarely celebrated for their own individual merit. One of the most recognizable allegories of “Manifest Destiny” is the 1872 American Progress painting by John Gast. It prominently features a white woman serenely guiding America out west—not unlike the Madonna forging the path along National Road. The image of a maternal white woman, like the Madonna of the Trail, portrays westward expansion as a romanticized struggle that resulted in positive national progress—rather than harmful imperialism.

Wheeling’s Madonna statue focuses on “the pioneer mothers of our Mountain State whose courage, optimism, love and sacrifice made possible the National Highway that United the East and West.”12 However, Madonnas in other states are more overtly racist. The base of the statue in Springfield, Ohio contains a line about commemorating the U.S. Army general who “vanquished the Shawnee Confederacy.” In fact, the New Mexico Madonna was supposed to be placed in Santa Fe, but Truman and the rest of the statue contingent received so much opposition from “an angry crowd, who did not believe it fit with the town’s indigenous and Hispanic heritage,” that it was installed in Albuquerque instead.13

The Madonna of the Trail statues do not acknowledge the trials and tribulations of indigenous peoples whose lands were stolen by the U.S. or the deaths and massacres that were often a result of American westward expansion. Nor do they acknowledge the African American pioneers who moved west, largely in part to escape slavery and stringent racial discrimination in the South.14 It focuses on the generic white woman and her family’s quest to build a new life—settling on lands that weren’t the U.S. Government’s to grant and displacing and destroying indigenous lives in the process.

Viewing the Madonna with 2021 Eyes

The way that we understand history changes all the time. The National Old Trails Road Association and the Daughters of the American Revolution did not design the Madonna with racist or sexist intentions—they were operating within the historical narrative popular at the time during the early 20th century. However, as more historical evidence and perspectives are analyzed, it makes us look at these pioneer monuments with more complexity.

So, the next time you are driving or walking along National Road near Wheeling Park, take a moment to stop by the Madonna of the Trail. Consider the historic women represented and celebrated through this monument. Consider the other women and groups of people who have been intentionally forgotten through this monument. Think about the ways in which all of their stories have been manipulated, celebrated, used, or omitted to promote a particular historical narrative about the U.S.

Women’s history and contributions are important to document and celebrate, but the commemoration shouldn’t perpetuate harm or false narratives against other marginalized groups of people.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 Harley Amos et. al., “Madonna of the Trail (Wheeling, WV),” Clio: Your Guide to History, February 17, 2021, accessed March 5, 2021, https://www.theclio.com/entry/2977.

2 Cynthia Culver Prescott, “Madonna of the Trail,” Pioneer Monuments in the American West, accessed March 5, 2021, https://pioneermonuments.net/highlighted-monuments/madonna-of-the-trail/.

3 Ibid.

4 “Wheeling Park Selected As Site Of National Old Trail Monument,” Wheeling Intelligencer, October 19, 1927, Ohio County Public Library, accessed March 8, 2021, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22madonna%20of%20the%20trail%22&i=f&d=01011926-12312020&m=between&ord=k1&fn=wheeling_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19271019_english_14&df=1&dt=2.

5 Rickie Longfellow, “Back in Time: The National Road,” Highway History, U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, June 27, 2017, accessed March 16, 2021, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/back0103.cfm.

6 “5,000 Witness the Dedication of “Madonna of the Trials,”” Wheeling Daily News, July 7, 1928, Ohio County Public Library, accessed March 8, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/research/wheeling-history/5600.

7 Amos et. al., “Madonna of the Trail (Wheeling, WV).”

8 “5,000 Witness the Dedication of “Madonna of the Trials,”” Wheeling Daily News.

9 Ibid.

10 Scott McCloskey, “Madonna of the Trail Statue is Restored,” The Intelligencer, December 26, 2012, Ohio County Public Library, accessed March 8, 2021, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22madonna%20of%20the%20trail%22&i=f&d=01011852-12312020&m=between&ord=k1&fn=the_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_20121226_english_9&df=1&dt=10

11 Cynthia Culver Prescott, “Think Confederate monuments are racist? Consider pioneer monuments,” Pioneer Monuments in the American West, August 10, 2018, accessed March 10, 2021, https://pioneermonuments.net/776-2/.

12 Amos et. al., “Madonna of the Trail (Wheeling, WV).”

13 Prescott, “Madonna of the Trail.”

14 Lorraine Boissoneault, “The Unheralded Pioneers of 19th-Century America Were Free African-American Families,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 19, 2018, accessed March 9, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/unheralded-pioneers-19th-century-america-were-free-african-american-families-180969400/.