The small staff of the Ohio County Emergency Management Agency is on alert 24 hours per day.

Every. Single. Day.

Storms, floods, chemical spills … everything the department reacts to is extreme except for one duty they’ve adopted because state lawmakers have yet to pass legislation that requires the companies involved with the fracking industry to map installed pipelines.

“Mapping these pipelines is essential, not just to the people of Ohio County but to the pipeline companies, too,” said Lou Vargo, the director of the Ohio County EMA. “It’s essential to everyone because there are pipeline emergencies all of the time, and we’ve seen what that can look like because of the explosions that have taken place in the state and across the country.

“The people and the first responders need to know where they are so when we get that 911 call, we’re not driving all over the county looking for the emergency. It’s a critical infrastructure, and we need to know where it is,” he continued. “That’s why we map each one of them and why we come up with an emergency action plan for each one.”

Vargo is concerned not only about the safety of Ohio County citizens but also for the safety of those installing the pipelines.

“These people are not from Ohio County or even from the Ohio Valley, so if one of their workers slips, falls, has a heart attack, or God forbid, gets trapped in some way, we need to know how to get EMTs to that person soon as soon as possible,” Vargo insisted. “In most cases they can’t tell us where they are working, so that makes it tough for us to get an ambulance to where that job site is.

“It’s a give-and-take situation, and it’s a safety situation for the people of Ohio County and for the people installing these pipelines,” he said. “That’s why it makes all the sense in the world for those companies to give us that information. In a lot of cases these areas are pretty far away from our roadways, so they need to let us know how they gained access.”

Common Sense?

Why state lawmakers have yet to establish mapping regulations is a question Vargo is unable to answer.

“You would think it would just be common sense, but that’s not something that they have done thus far,” Vargo said. “Now, Gov. Tomblin has developed a gas line/gas well safety forum, and they’ve had several meetings, and that has allowed us in Ohio and Marshall counties to express our concerns to state officials.

“We have suggested the mapping, and we have also suggested that the companies have at least one person on each crew that has been trained in first aid because if they are in the middle of a 100-acre farm, it may take us extra time to get to someone,” he said. “These projects are not taking place in downtown Wheeling. They are taking place in very rural areas, and it’s going to take us longer to get there, so having someone trained at the scene also just makes sense to us.

“Another question is, ‘How deep are the lines?’ While I am sure there are industry standards as far as how deep the lines are placed into the earth, I am not familiar with any state regulations for anything connected to the pipeline industry,” Vargo said. “That’s a concern for many reasons, and one of them is that erosion is inevitable. It’s going to happen.

“We are working very hard to get as much information as we can so we will be able to pass that information on to the people who take over this department in the future. That’s our responsibility,” he added. “New networks seem to pop up every day, so we’re trying to get all of them mapped.”

W.Va. Del. Shawn Fluharty has recognized this pipeline issue and believes the state’s legislators are failing the citizens when it comes to many facets involved with the fracking industry.

“This issue is one of many where our state has eagerly jumped in before doing our homework on it,” he said. “As we have seen the past few years, the pursuit for profit has been placed above the people by the majority of our delegates and senators.

“But this is a question I plan to continue asking in the future because everything I have seen come through our legislature has been focused on the industry and driven by the industry’s lobbyists,” Fluharty continued. “Forced pooling is a prime example. The industry wants to steal mineral rights from people who wish not to participate with the fracking, and that’s very, very wrong, in my opinion.”

Vargo, though, explained that his department has been very successful with mapping the pipelines that have been installed in both Ohio and Marshall counties because of cooperation from the companies, private citizens, and staff member Dave Weaver. Weaver, once employed by the Ohio County Assessor’s Office, transferred to the Ohio County EMA to lead the mapping effort.

“It’s a work in progress, and we continue to crack those eggs,” Vargo said. “We are having frequent meetings in both counties with representatives of these pipeline companies so we can all be on the same page.

“What we want to develop is a system that has all of the pipelines in the Northern Panhandle because eventually all of those pipelines are going to be connected in some way,” he said. “In most cases we are all working together, and that’s very important because of what could happen if something goes very wrong.”

The Mapmaker

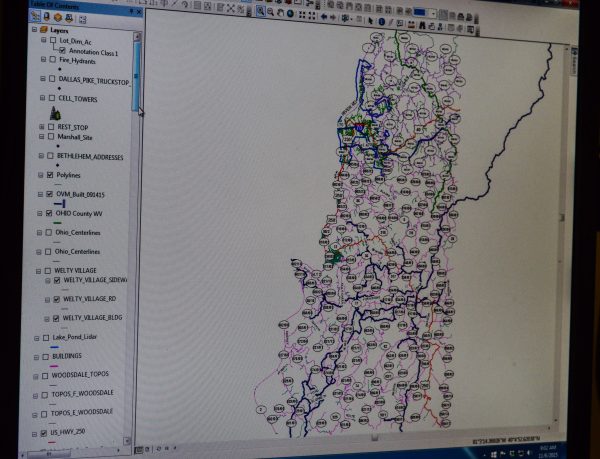

Weaver uses the ArcGIS software to map pipelines that lead from the 29 well pads in Ohio County and 119 pads in Marshall County and to processing facilities situated in both counties.

“The program allows me to place the pipelines on the GPS system so we’ll know where they are for many years to come. We started doing this back in 2012 because that’s when a lot of the work began here in Ohio and Marshall counties,” he explained. “It’s not state law, and there aren’t many federal regulations, either,” he continued. “But this information is what this department will need in case something happens. That’s why we keep a good eye on this activity.

“Marshall County has many more well pads and a lot more pipeline miles than Ohio County, but you have to remember that Marshall County is three-times the size,” Weaver said. “Marshall County also has more large facilities in it thanks to Williams and Markwest in Majorsville so there’s a lot more work to do when it comes to that area.”

Weaver has learned that each pipeline company creates at least two maps, one of which serves as an installation proposal and the other of the finished project.

“The second one is the ‘as-built’ map,” Weaver explained. “We have two companies in the area that are very forthcoming and that’s Williams and Markwest. They’ve been excellent to work with.

“The other companies have to be asked, and sometimes more than once. We negotiate with them and try to get them on board,” he continued. “There have been buyouts that have taken place so that’s one thing we try to keep up on every single day, and at times we only find out about pipeline projects because a resident tells us about it. That’s even happened with family members of mine.

“We do a lot of driving around the counties in an effort to keep track of where the lines are going, and we also talk to a lot of our local farmers because they see this work every day. But the number one thing we always do is trying to get the ‘as-built’ maps because it’s in everyone’s best interest for us to have that information,” Weaver added. “It doesn’t make any sense to keep it from us because it’s a lot easier and a lot quicker to evacuate an area if we have those drawings, and that’s something that reduces their liability. That’s business. So that’s where we’re at with mapping pipelines.”

Once the well pads are connected, the pipelines, Weaver reported, flow to processing plants in both counties.

“The vast majority of the lines in Ohio County are connected to the Markwest facilities across the Ohio River near Cadiz or to their facility in Majorsville,” Weaver reported. “That’s where the gas is separated and treated to get the product ready for market.

“All of the companies that we’ve met with have been very cooperative and they have been feeding us the data that we need,” he said. “What we have to do now is get everybody else into that room so that they can do the same thing. It’s a matter of communication, and it’s all about public safety.”

How Much More?

Vargo and his staff members can also monitor “laydown yards” for clues concerning future pipeline projects, included adjacent to Walmart at The Highlands in Ohio County. The property is owned by the Ohio County Development Authority and is leased by Carl Smith Pipeline out of Franklin, Tenn.

“There’s miles and miles of pipe up there right now, and they have to be going in somewhere locally because they wouldn’t have it there if it wasn’t. Where exactly is it going into the ground? That’s something we do not know yet,” Vargo admitted. “It’s unbelievable how much pipe they have delivered to that yard.

“At one time there was only one line of pipe at the yard at The Highlands, but that amount has dramatically increased recently,” he said. “Those pipes are the 36-inch pipes so they have to be for a major line. Those are the big ones and they will be used locally.”

Another mystery that exists throughout the n\Northern Panhandle pertains to the extent of pipeline work that will continue in the future. Southwestern Energy has been the only driller in Ohio County since acquiring all lease agreements from Chesapeake Energy earlier this year, and the company has spent the past several months fracking each of the 29 Marcellus Shale well pads.

“The pipeline projects have been moving right along at a pretty good pace, and we expected that to be the case because these companies have to get those well pads connected so they can deliver the product to market,” Vargo explained. “They couldn’t possibly truck out all of the gas that is being harvested, so these pipelines are essential to the industry.

“There’s a lot taking place right now, but I don’t think they are close to being finished at this point,” Vargo said. “I believe there’s a lot more of these lines that have to be installed.”

“I couldn’t even begin to guess,” Weaver said. “Where they are with building this pipeline network is anyone’s guess at this point. Only the companies know that answer, and I’m not sure they even know at this point.”

But Vargo and Weaver will not cease with their efforts, and one motivating factor is the explosion that took place on Dec. 11, 2012, in Sissonville, W.Va. A 20-inch high-pressure natural gas pipeline owned by Columbia Gas Transmission that ran through the Kanawha County community ruptured with so much force that debris was tossed more than 40 feet from the site.

The released gas ignited and charred approximately 800 feet of Interstate 77 and destroyed three nearby homes. No injuries were reported, but several other homes were damaged by the extreme heat produced during the incident.

Investigators with the National Transportation Safety Board determined in March 2014 the cause of the rupture was external corrosion and a lack of recent inspections. Agency officials also determined the corrosion could have been discovered by a pipeline operator.

“That’s why it’s so important that we are doing this because in the years to come the locations of these lines will grow over and be invisible. We can see where they are now, but that won’t be the case for generations of the future,” Vargo said. “These properties could be sold in the future, so what happens if someone wants to build a pool or a barn or something? We always hear, ‘Call before you dig,’ but if we don’t know where they are, we can’t help those people.

“I believe we are safe, but another thing we have to keep in mind is that each piece of pipe has to be welded into place, and they don’t check every weld because the state doesn’t mandate that,” he added. “It’s a human weld, and mistakes take place, so eventually something might pop.”

(Photos by Steve Novotney)