When the earth rattled under the tiny country of Nepal, Vishakha Maskey was unaware that her parents and relatives had been chased from their homes and forced to sleep in an automobile similar to the size of a Honda Civic. Her cell phone battery was empty, and the unit shut off.

After charging her phone, she learned that her folks, Vishnu Raj and Sharda Maskey, had survived the worst earthquake to strike Nepal in more than 80 years. On April 25th, a 7.8-Richter-Scale quake shook so hard the death toll eight days later extended to 6,621, and more than 14,000 citizens were injured.

The national news coverage caused Maskey to have nightmares, but those bad dreams faded in the days following, and that has allowed this West Liberty University professor to return to concentrating on a career she never thought she would adopt in a place she never imagined living.

She is married to West Virginia native Jesse Gandee, and they have a pair of daughters, 9-year-old Lavani and 6-year-old Juniper. After earning her undergraduate degree in Kathmandu, she accepted a scholarship and chose the University of Maine. After meeting her husband-to-be there, she followed his advice to further her education at West Virginia University, where she acquired her doctorate degree.

Today Maskey has extended her teaching into two separate schools at West Liberty, where she instructs students in both the schools of business and liberal arts. The reason is simple: She is interested in more than the world of business and finance and believes the typical student is, too. The world is not just about money, she insisted, and Maskey believes employers now need to improve conditions for their employees, or profits will decline. She watches the world far beyond her home in the Dimmeydale section of Wheeling, and she considers the global society’s unborn children when concentrating on her goal of promoting recycling here in the Upper Ohio Valley.

Maskey’s efforts to raise awareness included a class study of the use of plastic bags at grocery stores. The students learned how the bags are produced, and they learned what happens to them after the leave the stores, and they also composed letters to congressional members and grocery store managers.

Maskey also believes grocery stores should offer special coupons to patrons who use cloth bags instead of accepting the plastic ones.

“It saves the stores money when people use the cloth bags, so why shouldn’t we get something in exchange when we are saving those companies money?” she said. “It makes me think how people survived before the plastic bag was invented in the 1970s.”

Novotney: Are your parents still living in a car after last weekend’s devastating earthquake?

Maskey: I just talked to my father, and he told me that they moved back to their house on Thursday, so that was good news.

They left the house because there have been so many aftershocks, and no one knows when they will happen and how big they will be. One of the aftershocks was a 6.5 on the Richter Scale, and that’s pretty big all by itself. And there was another one on Thursday, and it was a 4.5. There was a warning that people should be out of their homes just in case.

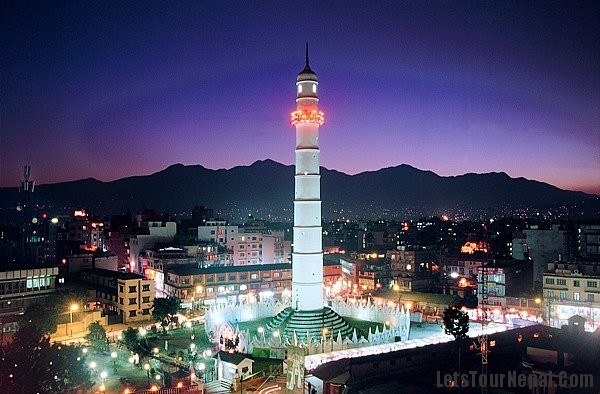

Novotney: The Dharahara – also known as the Bhimsen Tower – was constructed in 1832, and it was completely destroyed. What did that monument mean to you and the citizens of Nepal?

Maskey: For the Nepalese of Nepal, is was the same thing as the Washington Monument is to the people in Washington, D.C., and the people of America. It also was where thousands of people would gather just as they do near the Washington Monument.

It was a symbol of our country, and it was very historical, but now it is gone.

Novotney: Where were your parents at the time the earthquake struck on April 25?

Maskey: They were at home at the time, but only because my father didn’t want to go shopping like my mother wanted to. Right around the time when they were planning to have lunch, my mother suggested that they go shopping because they wanted to send something here for my daughter.

But my father was very reluctant because he was tired, and my mom doesn’t drive.

My mom said that if they had been shopping, they may have been hurt or worse because where you go shopping is nothing but one building after another. And that’s also where a lot of the people died. My parents were lucky.

Novotney: Tell me about their house in Kathmandu.

Maskey: The houses in Neal are not built the way they are here. You have to dig way down and put all of this mesh iron on the bottom, and then they build on top of that. And when they are building new houses in Nepal, they are always thinking about earthquakes because of what has happened there before.

My parents’ house is a newer house, and it survived the earthquake, but I did urge them to have a structural engineer look at it because you really never know. It’s a five-story house just like all the others in that area. Everyone wants to live in Kathmandu, so the lots are small, so they build the five floors so you have enough space to live.

Novotney: When the earthquake hit your native country, what were you first thoughts?

Maskey: I didn’t know about it until the next day because my children had a show at school. Then the next morning I realized my cell phone was dead, and when I put it on the charger, I saw all these messages from my family members.

The first message I read asked if my dad and mom were OK from my younger brother who lives in Pittsburgh. And then my older brother who lives in Chicago answered that he had found out they were OK and that they were safe.

We also found out that my uncle and my aunt were OK, too.

Then I found out that they had to go to an open space where many others were, but at night it got colder, and that’s why they had to sleep in their car. It’s a tiny car, too. Think of a Honda Civic.

They would go back in the house to take a shower and to cook, but they weren’t supposed to spend a lot of time in the house because of the aftershocks. When those hit, my mom told me that she would see everyone running out of their homes.

It’s a long process. If it’s a hurricane or a tsunami, it hits, and then it’s over, but that’s not how it goes with earthquakes. No one can predict them, but it’s a lot like Wheeling there because everyone just started helping each other. And the people who are now refugees are getting the support from everyone else.

Novotney: Your family members are OK, but did they lose friends in the earthquake?

Maskey: Oh gosh, yes, but my dad really hasn’t walked around a lot yet to see who is alive and who is dead. He did drive on Thursday because he had to go get food and supplies, and he told me that he thinks things are starting to get back to normal, but he did say that they are still digging people out of the rubble because so many structures collapsed to the ground. It is nice that Nepal is getting so much international support, but thousands of people died.

But there have been miracles in Nepal like the 4-month-old baby that somehow survived, and the people of Nepal needed that so they know that miracles are possible. All of the footage that I have seen has been terrifying to me, but so many people are trying to help that little country.

When I was 14 or 15, there was an earthquake, and it’s been very sad for me to see it happen again. That was in the early 1990s, and it has to be the worst way to die – to be buried alive unable to breathe. I don’t even like thinking about it.

Novotney: Besides the telephone, how have you been communicating with your family members in Nepal?

Maskey: Thank goodness for technology and social media because it’s been pretty easy to connect with them and to find out how everyone has been doing. I am on a Facebook page with all of my cousins, and that made it easier to tell that everyone was OK.

Novotney: If you and your two brothers live in the United States, why have your parents remained in Nepal?

Maskey: Although they come to visit us once every year, they have a sense of community there. It is their home. They would miss it too much. They are retired, so they are hanging out with their family and their friends. And in Nepal, it’s all about drinking tea with each other.

Every time they come here to visit, they usually want to run home because they miss it that much, but they do want to move here eventually because in Nepal a parent’s whole purpose centers on their children. They call us every day, and I know they want to be closer, and eventually they will have to move here so we can take care of them.

Novotney: Why did you and your two brothers make the decision to come to America?

Maskey: It’s the land of the free, and we could accomplish what we wanted to accomplish here and not there. I love Nepal, but this is where I can do what I am doing now. My parents always told us that life is not about money, it’s not about looks, and it’s not about what you wear. It’s all about education, education, education. They always told us that once we were educated as much as we could be, the rest would fall into place.

I had reached the maximum in education, so I believed coming to the United States would be the best choice to continue my education. I applied for one scholarship, and I received it, and I had an aunt who was a professor at the University of Maine, so that’s where I went to continue.

And that’s where I met this man from West Virginia, and that man is my husband today. It was funny because since I was a child, I have always sung “Almost Heaven,” because we had mountains everywhere there, too.

Novotney: How did you end up living in Wheeling, W.Va.?

Maskey: When my husband was finished at Maine, he went to WVU, and I was living in Washington, D.C. At the time I was trying to decide whether or not to accept a full-time job there, and my husband suggested that I go to Morgantown and take the tour. When I was there, I met a professor who was in charge of the program I was interested in, and he offered me a full assistantship to earn my doctorate degree. I wasn’t sure I wanted to do it because I was already so sick of school at that point, but I called my mom and asked her, and she reminded me what was most important – education.

Once we were finished in Morgantown, my husband accepted a job in McMechen with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and he told me we would have to move to a place called Wheeling. I had never been here before.

Novotney: How did you end up teaching at West Liberty University?

Maskey: My husband, Jesse, kept encouraging me to teach, but I never wanted to teach. My mom was a teacher for 35 years, and it seemed like her job never ended. I remember seeing her grading papers every night, so it seemed as if there was no end in sight. Her work never ended, so I always said to myself that I was never going to do that.

But then I saw that West Liberty had an opening in 2008, so I sent in a resume just to see what would happen. I went to the all-day interview, and at the end they offered me the position. I may have thought I didn’t want to teach, but I am very thankful that I decided to go to the interview and accept the position.

I love it. My students’ testimonials on how my classes were valuable make this job worthwhile.