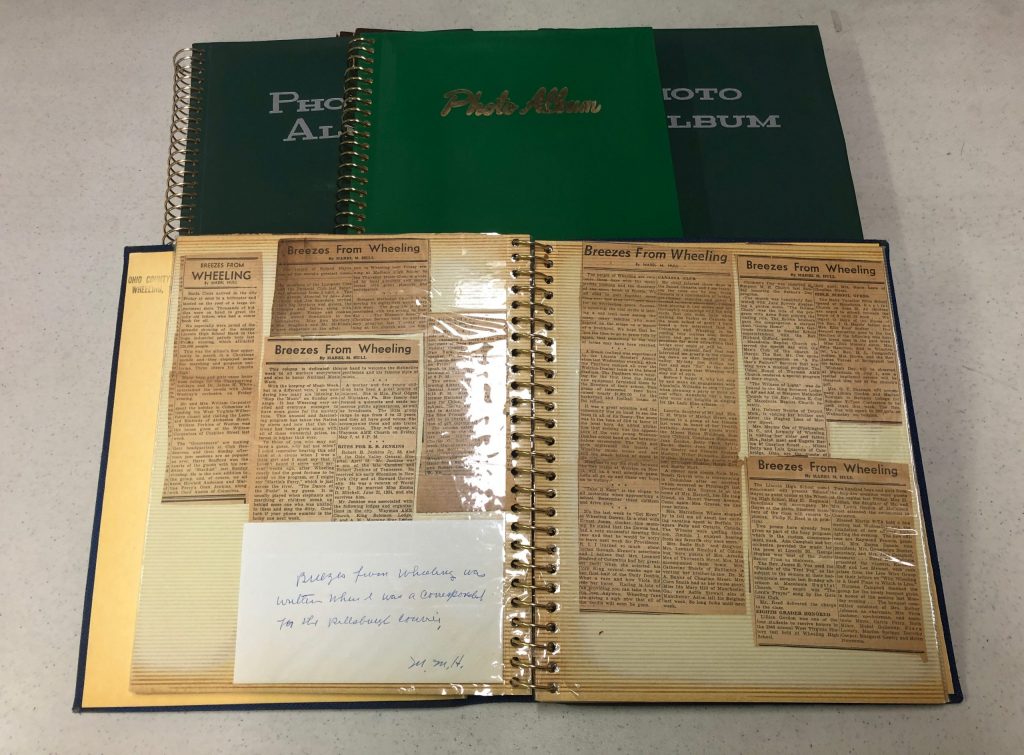

Mabel Hull first became a mystery due to a collection of her scrapbooks at the Ohio County Public Library. The scrapbooks primarily contain clippings of columns she wrote in the Wheeling News-Register and The Pittsburgh Courier. According to the library’s records, the acquisition information for the scrapbooks are unknown—no one knows who donated them or how the library obtained the books.1

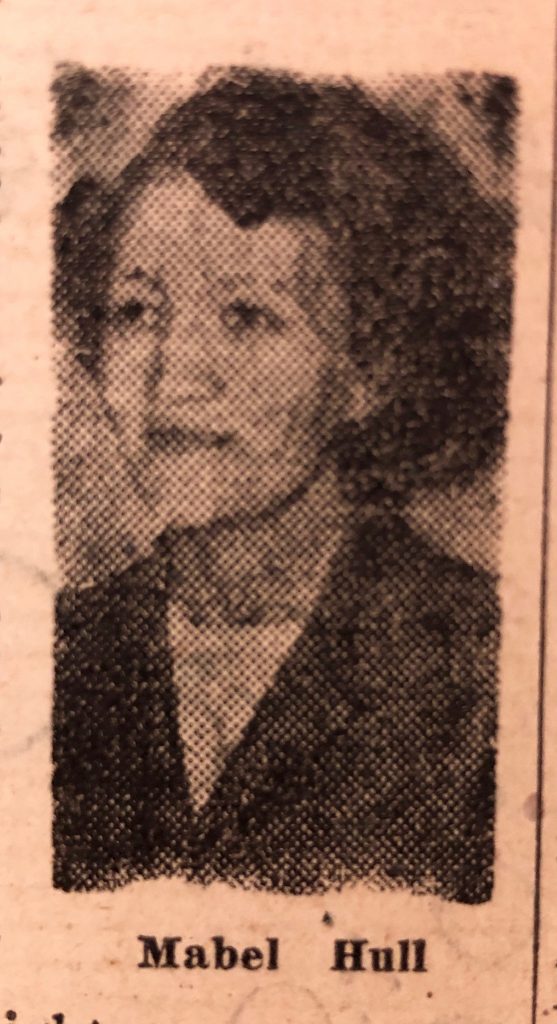

Mabel Hull was an African American woman living in Wheeling, primarily in the 1940s to 1970s. Women—especially Black women—were underrepresented in the newspaper industry during the middle of the 20th century, so Mabel and her work caught my interest. In my own career, I am committed to elevating unheard histories, so I set out to write a short quick piece about a historic Black female journalist in Jim Crow Wheeling.

However, once I started to dig a little deeper, it became remarkably hard to find information on Mabel’s life and her work as a journalist. Many of the “go-to” sources like census records and obituaries turned up empty. The handful of people who seem to know everyone in Wheeling (past and present) had never heard of her. Even her old Wheeling address on Morrow Street no longer exists—demolished as part of Wheeling’s urban renewal movement.

The journey of researching Mabel Hull’s life and work has been a series of twists and turns. At times, exciting and exhilarating, and at other times, frustrating and heartbreaking. There would be days that I wasn’t even sure if I had the “right” Mabel Hull, and other days that I would finally find her in a census that I had been searching for weeks.

Cracking the Code

After a few months of on-and-off research, it felt like the trail was getting cold. I had exhausted many sources and records, but it only resulted in little tid-bits here and there. I learned facts like how she lived on Morrow Street, but could not find her in the 1940 US Census. Mabel clearly wrote for the newspaper as evidenced by her scrapbooks, yet I couldn’t find any mention of her writing career anywhere else. I still felt like there had to be more to Mabel’s story. My last-ditch effort was to attempt to get in contact with her family—but I wasn’t hopeful.

Almost all of her children were confirmed dead—with the exception of her third daughter, Sally, who is in her 90s. By combing through Mabel’s children’s obituaries, I managed to find a granddaughter’s email address and decided to shoot my shot.

I felt like I won the lottery. Within 24 hours, I was in contact with several of Mabel’s granddaughters, including Gina Stewart, who serves as the family historian. People started calling or emailing me from all over the country, sharing their memories of Mabel and her life.

Due to scattered appearances in historical documentation, even in supposedly comprehensive records like censuses, Mabel felt somewhat like a tenuous ghost—almost as if I dug too deeply into her history, she would dissipate. But meeting Mabel’s family grounded her and convinced me that she would never disappear into the attic of people history has forgotten. Using a combination of official records and the stories from those who knew Mabel and Mabel herself, here are some ups and downs in the complicated life of an ordinary woman with an incredible story.

Mabel’s Origin Story

Mabel Mariah Johnson was born on May 29, 1904 in Moorefield, West Virginia.2 While there are not many records from her childhood, Mabel herself wrote a short memoir of memories from her early childhood. Her family lived in a log cabin out in rural West Virginia, making their own clothes and food, but also experiencing noteworthy events like the first railroad coming through town. In terms of her parents, according to Mabel, “my father looked like a white man and he grew a long mustache that ended in a curl on each side of his face. My mother was a short, fast brown skin woman with beautiful black hair.”3

According to numerous family accounts and photographs, Mabel herself was a light-skinned Black woman, who, in some situations, was mistaken for or could pass for a white woman.4 This part of her identity would complicate her life in the racially segregated Wheeling.

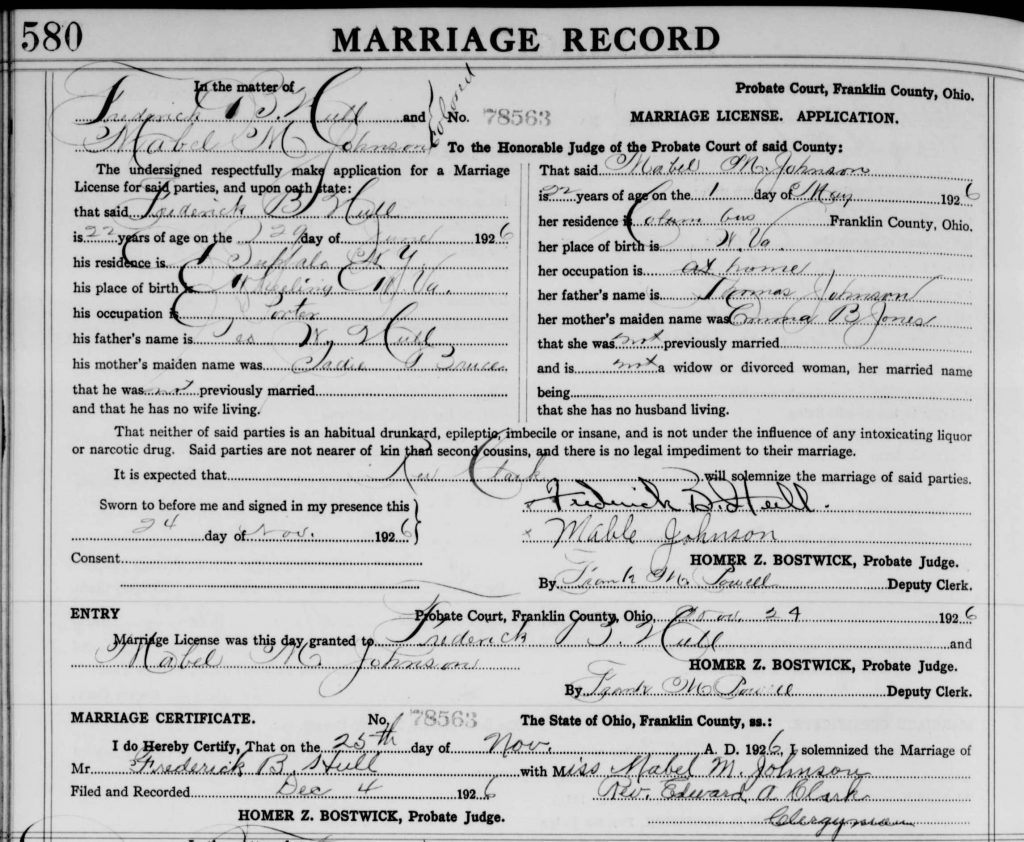

At the age of 22, on November 25, 1926, Mabel married Frederick Burdette Hull in Columbus, Ohio. At the time, Frederick’s listed residence was Buffalo, New York and Mabel’s was Columbus.5 It’s unclear how they met, but Frederick’s family was from Wheeling, so it is likely he was back in the area to visit at some point.

Between 1927 and 1938, Mabel and Frederick had seven children; six of whom lived to adulthood: Jacqueline, Jeanne (died as an infant), Sally, Frederick Jr., George, Bruce, and Garrett.6 Sally was actually originally named “Fredimarie,” a combination of her parents’ names, but when Frederick Jr. was born a year later, they changed her name to Sally.7

The Family Gets More Complicated

According to the 1930 US Census, the Hull family lived in Buffalo, New York as Frederick worked as a porter for the Pullman Car Company.8 However, after moving back to the Ohio Valley area, Mabel and Frederick separated in the mid-1930s, even though their last child, Garrett, was born afterwards. All of the children—with the exception of Garrett—lived with their father, eventually moving to Findlay, Ohio. While he was sent for short periods of time to live with other family members, Garrett remained based in Wheeling with Mabel.9

Depending on which family member you talk to, the reason for the separation of Mabel’s children varies. Some descendants believe it had to do with friction in Mabel and Frederick’s relationship. Perhaps the most generous theory comes from Garrett, in an academic paper he wrote about his adolescence when he was about 30 years old. He wrote (in the third person), “when Garrett was three months old, his mother underwent minor surgery.” Due to her surgery, Mabel may not have been able to care for all of her children, especially while also needing to provide as a single mother.10 Other family members are adamant that surgery had nothing to do with Frederick’s custody of most of the children and a few even suggest a court was involved, however, no court records have been located, at least in Ohio County.

Mabel’s relationship with her other children was complicated, especially by the fact that they grew up and lived apart from her for most of their lives.11 According to Sally, Mabel’s only living child, after her parents’ divorce, the older children basically lost contact with their mother’s side of the family.12 Garrett remembered his relationship with his older siblings to be “somewhat distant,” but that they would occasionally visit each other.13

Despite the remembered animosity, there is still evidence of love and affection. One of the only non-newspaper items in Mabel’s scrapbooks was a letter from Bruce, George, Sally, Frederick, and Jackie, postmarked March 1948. It gave updates on their lives in Findlay and concluded with dozens of “x”s, presumably representing kisses.14

Nonetheless, the strained relationship did trickle down and affect some of Mabel’s grandchildren. Even though she is now one of Mabel’s strongest advocates, Gina Stewart (Bruce’s daughter), remembers her father not taking her to see her grandmother very often due to lingering resentment.15 Gina didn’t connect with Mabel until her late teens/young adulthood, while her siblings never formed a relationship with Mabel. Other grandchildren, such as Jackie and Garrett’s children, grew up enjoying a close relationship with Mabel, seeing her for the holidays and visiting her in Wheeling.

Mabel, A Newspaper Woman

Even though her scrapbooks, chock full of her newspaper clippings, are one of the only physical traces left of Mabel in Wheeling, her work with the newspapers remains the hardest to find any information about.

Despite working full-time, Mabel still managed a column in the Wheeling News-Register during the 1940s and 50s, mostly covering society news from Wheeling’s African American community. Most of Mabel’s clippings do not include dates, making it difficult to pinpoint exactly how long she wrote for the paper. Her subjects ranged from the Lincoln School to the YWCA’s Blue Triangle Branch to church activities and more. Since the newspaper was a side gig, Mabel would occasionally weave her own jobs into her column, such as events that she would see while waitressing at the Hoge-Davis Tearoom on 14th and Market Streets. Mabel also covered more prominent events like the Freedom Train stopping in Wheeling or the success of Everett Lee, the famous Black orchestra conductor from Wheeling.16

In addition to her full-time job and newspaper writing, Mabel was also involved in the local community. She not only taught sewing lessons at the YWCA Blue Triangle, but she also served on numerous committees including as secretary for the Committee of Management, Executive Committee, and the Interracial Committee.17 Throughout her activities, she helped raise money for WWII loans, mentored young working girls, and even gave speeches to local groups, like the Elm Grove Women’s Club.18 Mabel’s community involvement informed her articles about the news of Wheeling’s African American community.

During the late 1940s, Mabel also wrote a column called “Breezes from Wheeling” for The Pittsburgh Courier, also covering the society news from the African American community in Wheeling.19 The Pittsburgh Courier was one of the most popular Black newspapers of the 20th century, regularly advocating for Black representation and equality. It often had prominent contributors such as Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. DuBois, and Zora Neale Hurston—Mabel was in good company.20

Mabel’s articles and scrapbooks are important artifacts of a thriving African American community in Wheeling during the Jim Crow era. In general, according to historian William Sturkey, “Black communities received far less coverage than their white counterparts,” but Mabel’s articles preserved the memories of her elderly neighbors on Morrow Street, celebrated national Black leaders in Wheeling, and encouraged support for local organizations like the YWCA and the NAACP.21

So…What Happened to Mabel’s Newspaper Career?

While several people have their opinions or suspicions, no historical records explain definitively why Mabel stopped writing for the Wheeling News-Register or The Pittsburgh Courier.

In part of the Hull family memory, according to her grandson, William Williams, Mabel might’ve been let go from the Wheeling News-Register when they found out she was Black. She had written a story about her daughter Jacqueline (William’s mother) and her family’s experience moving to Japan during the 1950s.22 While Mabel could pass for white, Jacqueline had darker skin, which supposedly somehow reached the newspaper.

What is curious and complicates this theory is that Mabel wrote predominantly about Wheeling’s African American community…it seems unlikely that the paper would not be aware that she was part of that community. In addition, the article about Jacqueline’s family moving to Japan was published on June 7, 1953, but Mabel continued to publish columns into 1954 and 1955.23

What makes a little more sense is that Mabel wasn’t actually in Wheeling at the time. The City Directories list Mabel living at 1041 ½ Morrow Street from 1946 to 1956—but she is nowhere to be found in the directories from 1957 to 1961.24 Priscilla Hull, Garrett’s wife and Mabel’s daughter-in-law, confirms that Mabel moved to Danbury, Connecticut in the late 1950s after Garrett graduated high school and started to attend West Liberty State College (known today as West Liberty University).25 Mabel did eventually move back to Wheeling in the early 1970s.

No matter the reason why Mabel stopped writing for the newspaper—whether it was as benign as choosing to leave the position due to other responsibilities, or as malignant as racism—it was clearly an important part of her life and leaves behind a valuable record in Wheeling history.

Anything But Straightforward

As I listened to children, grandchildren, and in-laws describe Mabel’s personality, likes/dislikes, funny quirks, and life philosophies, they filled the gaps and my understanding of Mabel became more and more vivid. Seemingly random things that didn’t make sense before, like all of Mabel’s clippings of New York art exhibits, suddenly became clear the moment Priscilla mentioned how much Mabel loved the Hudson River School painting movement.26 Throughout this journey, some of Mabel’s mysteries were resolved and some will continue to go unanswered, as evidence of an intriguing and complicated life.

Late in life, Mabel began to suffer from dementia, which was ultimately diagnosed as Alzheimer’s.27 She passed away in 1995 at the age of 90 in New Hampshire while living at an assisted living center near Garrett and Priscilla. Garrett is most likely the person who donated Mabel’s scrapbooks to the library. Mabel was returned to West Virginia and buried at Thorn Rose Cemetery in Keyser—less than an hour from where she was born.28

A person’s life is anything but straightforward. There are memories that people remember completely differently and holes that may never be filled. It is a collage of contradictions, struggles and successes, beautiful memories, and aspects some may like to forget.

Thank you Mabel, for letting me meander through your story with you for a while.

For those interested in hearing more about Mabel Hull, attend or tune into the Ohio County Public Library’s Lunch With Books Program on June 29, 2021 at 12pm. To learn more about this event, click here.

Special thanks to all of Mabel’s family, especially Gina Stewart, for their time, information, and stories.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “Mabel M. Hull Scrapbooks, 1940-1965,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed June 3, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/5751.

2 Gina Stewart, “Mabel Mariah “Kit Kat” Johnson Hull,” Find-A-Grave, March 6, 2012, accessed March 1, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86345128/mabel-mariah-hull.

3 Mabel Johnson Hull, “My Childhood,” unpublished.

4 Gina Stewart, phone interview by Emma Wiley, April 14, 2021.; William Williams, phone interview by Emma Wiley, April 19, 2021.

5 “Ohio, County Marriages, 1789-2016,” FamilySearch, accessed March 1, 2021, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9392-S593-7L?i=404&cc=1614804&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AX868-G23.

6 Garrett Johnson Hull, “Personality and Social Structure: A Self Analysis,” Unpublished paper, December 3, 1968.; “1930 US Census,” FamilySearch, accessed March 1, 2021, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRH1-HLS?cc=1810731&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AX7ZM-P4F.; “Mabel Mariah “Kit Kat” Johnson Hull,” Find-A-Grave, March 6, 2012, accessed March 1, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86345128/mabel-mariah-hull.

7 Sally Jones, phone interview by Emma Wiley, April 14, 2021.

8 “1930 US Census,” FamilySearch, accessed March 1, 2021, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRH1-HLS?cc=1810731&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AX7ZM-P4F.

9 Garrett Johnson Hull, “Personality and Social Structure: A Self Analysis,” Unpublished paper, December 3, 1968.

10 Garrett Johnson Hull, “Personality and Social Structure: A Self Analysis,” Unpublished paper, December 3, 1968.

11 Gina Stewart, phone interview by Emma Wiley, April 14, 2021.

12 Sally Jones, phone interview by Emma Wiley, April 14, 2021.

13 Garrett Johnson Hull, “Personality and Social Structure: A Self Analysis,” Unpublished paper, December 3, 1968.

14 “Letter to Mabel Hull from Bruce Hull”, March 30, 1948, Mabel M. Hull Scrapbooks, 1940-1965, Ohio County Public Library.

15 Gina Stewart, phone interview by Emma Wiley, April 14, 2021.

16 “Mabel M. Hull Scrapbooks, 1940-1965,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed January 15, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/research/mabel-m.-hull-scrapbooks-1940-1965/5751

17 “Committee, Management,” Blue Triangle Branch of the YWCA Wheeling Records, Ohio County Public Library.; “Committee, Inter-racial,” Blue Triangle Branch of the YWCA Wheeling Records, Ohio County Public Library.

18 “$874,513.75 Added to Second War Loan Fund Drive in Wheeling For Tuesday,” Wheeling Intelligencer, April 21, 1943, p. 3.; “Today’s Calendar,” Wheeling Intelligencer, April 27, 1950, p. 8.

19 “Mabel M. Hull Scrapbooks, 1940-1965,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed January 15, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/research/mabel-m.-hull-scrapbooks-1940-1965/5751

20 “Newspapers: The Pittsburgh Courier,” PBS, accessed February 17, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/courier.html.; Brady Smith, “Let’s learn from the past: the founding of The Pittsburgh Courier,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 17, 2017, accessed February 17, 2021, https://www.post-gazette.com/life/my-generation/2017/08/17/The-Pittsburgh-Courier-African-American-newspaper-founder-Edward-N-Harleston/stories/201708170025.

21 William Sturkey, “The Game is Changing for Historians of Black America,” The Atlantic, May 4, 2021, accessed May 14, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/05/putting-black-history-back-record/618747/.

22 William Williams, phone interview by Emma Wiley, April 19, 2021.

23 “Mabel M. Hull Scrapbooks, 1940-1965,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed June 3, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/5751.

24 Polk’s Wheeling City Directory, (Richmond, VA: R.L. Polk & Co., 1946-1969)

25 Priscilla Hull to Emma Wiley, email, June 22, 2021.

26 Priscilla Hull to Emma Wiley, email, April 18, 2021.

27 Priscilla Hull to Emma Wiley, email, April 20, 2021.

28 “Mabel Mariah “Kit Kat” Johnson Hull,” Find-A-Grave, March 6, 2012, accessed March 1, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86345128/mabel-mariah-hull.