Imagine Wheeling without Oglebay Park. …

At one point that nightmare was nearly reality.

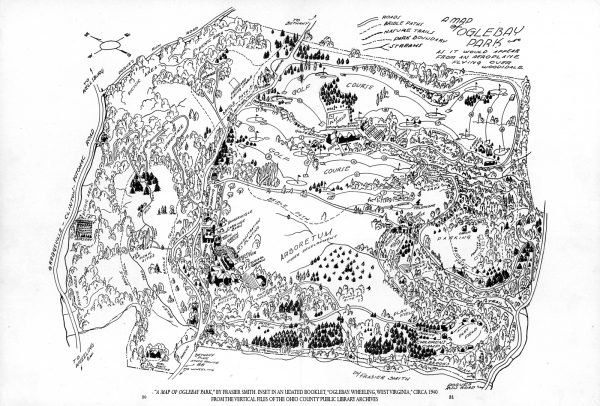

As one of the largest self-sustaining city parks in the country, Oglebay Park rubs shoulders with just a select few municipal parks of its size and grandeur. Covering a sprawling 1,700 acres of lush rolling hills, the park welcomes visitors of all ages from across the country and the world. Oglebay Park offers a wide array of activities for people of all ages, including horseback riding, skiing, kayaking, hiking, sledding, swimming, tennis, mini-golf and so much more. Wilson Lodge, cottages and estate houses make overnight guests feel at home. Although Oglebay Park’s roots are anything but humble, the one-of-kind destination has at its core the incredibly simple and yet overwhelming powerful mission: to be a “park for everyone forever.”

And yet the City of Wheeling mulled over taking ownership of the grounds for two years. While it seems almost preposterous in 2018, a little over 90 years ago the fate of one of Wheeling’s most beloved jewels was undecided.

A Brief History of Oglebay Park

A Brief History of Oglebay Park

The land on which Oglebay Park now spans was awarded by the Commonwealth of Virginia through a land grant to Silas Zane in 1784 because he had lived on the land since establishing his claim through tomahawk rights in 1775. Along with his wife Catherine and their children, the Zanes lived in a small log cabin on 400 acres of land that would eventually become Oglebay Park. The Zane family owned the land until 1812 when it was purchased by Noah Linsly, who would later found what is now The Linsly School. After his death, the land was purchased by Samuel Sprigg, a highly successful attorney who became the mayor of unincorporated Wheeling in 1828 and used the land mostly for sheep farming.

Upon his death, Sprigg left parcels of the property to his three daughters. His daughter Elizabeth, who was married to Dr. Hanson Chapline, inherited the portion of land on which the Oglebay Mansion now stands. In 1846, the Chaplines completed a square farmhouse, which would become the central unit of the Oglebay Mansion. (Their daughter Ann and her husband, William Miller, would later buy the land back from its then-owner in 1869.)

In 1856 an Englishman from Pittsburgh, George Weatherall Smith, purchased the farmhouse and 416 acres of adjoining land. He named the estate Waddington Farm after his family’s ancestral home, Waddington Heath. Smith owned and operated Wheeling Brewery at 1700 Chapline St., and locals remember seeing him riding his horse to the brewery downtown and back to Waddington each day.

In 1863, his business nearly ruined by the Civil War, Smith purchased a brewery in Canada. He sold Wheeling Brewery and Waddington Farm in 1864. In a June 3, 1864, article in The Intelligencer about the pending sale, Waddington Farm was described as being “most admirably improved. No good farmer can walk over the farm and truly say that there is anything wanting. This land is very productive and the whole is now blooming like the rose.”

In the years that followed, the farm changed hands multiple times (including those of the farm’s only woman owner, Frances Phillips) until 1888 when it was purchased by A. Allen Howell, the father of Sallie Howell, who had married a Wheeling-raised Cleveland industrialist by the name of Earl W. Oglebay in 1881. In 1900, Oglebay purchased the now 25-acre estate from his mother-in-law, becoming the 13th owner of the land. Over the next 25 years, Colonel Oglebay would invest more than money into the farm. He devoted much of his time and energy into learning about agriculture and developing the land into a fine country estate and model scientific farm.

Under Oglebay’s direction, the farmhouse was expanded, more than 60 other buildings were erected or rebuilt, roads were constructed, and landscaping shaped the rolling hills into a summer oasis for the Oglebay family, whose time on the farm eventually extended from June into December. Waddington Farm soon became known as an experimental farm where people from all over West Virginia could come and learn state-of-the-art farming methods in both agriculture and animal husbandry. By 1905 the farm had grown to 750 acres.

After studying agriculture in Europe, Oglebay realized that successful farming required an owner to be present not just in the funding of farm projects, but in the knowledge of the smallest details of its inner workings. About this approach to farming he observed, “The master of the land lives by the land and he gives the land the same attention that Americans give to banks, stores, mines and factories.” Oglebay lived out this philosophy as he was thoroughly involved in the day-to-day workings of the farm, even when he was in Cleveland. Livestock and crop reports were delivered to him regularly so that he could make suggestions for optimal growth.

When Earl W. Oglebay died in 1926, he bequeathed Waddington Farm to the city of Wheeling for as long as it “shall operate for the purpose of public recreation and education.” Today, few of us could imagine that anyone in Wheeling would consider rejecting this generous gift, but newspaper editorials and letters to the editor of the time tell a different story. It took the people of Wheeling two out of the three years Oglebay’s will mandated to finally accept this million-dollar gift.

A City Conflicted

In hindsight, their hesitance is understandable. The City of Wheeling had just accepted responsibility for Wheeling Park, which at the time stretched to over 130 acres, and the people expressed concerns over the fiscal consequences of taking on the 750-acre Waddington Farm. City leaders worried that there would not be enough money to both maintain the land and its buildings while also carrying out Oglebay’s wishes for recreation and enjoyment for all.

Generally, though, the people of Wheeling were highly in favor of taking on Waddington Farm. In fact, to test the pulse of its citizens on the issue, the Wheeling Register added a tear-out poll to the newspaper in January 1927. Near the end of the month, they had collected 300 surveys, and all but nine responders enthusiastically agreed that Wheeling should accept the bequest. In a letter that appeared in the paper, prominent citizen and Woodsdale resident, Sarah Paull, urged her fellow townspeople to support the decision by arguing, “I don’t see how any citizens could fail to see what the possession of the park means to the health and happiness of ourselves and children, especially as the funds to maintain it are clearly in sight.”

Following the early results of their poll, the editors of the Wheeling Register under the direction of owner W. C. Ogden implored the City of Wheeling to take on Oglebay’s gift. In the Jan. 23, 1927, issue, they write, “The Register cannot understand why any person should oppose the taking over of the park.” They ended their argument with clear and definite, “Accept!”

Wheeling attorney W. C. Grimes wrote more forcibly: “To refuse this gift would be an insult to the memory of Wheeling’s greatest philanthropist and friend.”

There were dissenters, of course, and those voices speak to some of the concerns that people have today in regard to Oglebay Park: accessibility in terms of both transportation and affordability. Albert Kyseka stated that he was opposed to the city accepting Oglebay Park because “1. Our present park is adequate. 2. If there was a demand for more parks then we should have them within the city limits because people cannot afford the transportation cost.”

Eventually, the mayor of Wheeling, W. J. Steen, wrote to Crispin Oglebay, Earl Oglebay’s nephew and estate executor, and asked for help with financing the run of the park for the first year. Sarita Oglebay Burton Russel, the Oglebays’ only daughter, agreed to finance the park operations up to $75,000 for the city’s first year of ownership. In her letter to Mayor Steen, Russel said she thought it was a good plan for her to support the park in its first year because it would give the Wheeling Park Commission time to “acquire an experience as to the needs of the property for its best interest, and in preparing its budget for the next year.” (Upon her death in 1930, she willed $100,000 to the ongoing growth and maintenance of Oglebay Park.)

“City Accepts Waddington”

Not long after Sarita’s letter arrived, Wheeling City Council voted unanimously to accept Waddington Farm to be renamed Oglebay Park to honor Colonel Oglebay’s generosity. If not for her support, the ownership of Oglebay Park might well have reverted back to the heirs. When the City of Wheeling took possession of the farm in July 1928, it set in motion 90 years of recreation, education and amusement for what has become close to a million visitors per year.

The day after the council said “yes!” to Oglebay, the headline of the Wheeling Intelligencer boldly declared: “City Accepts Waddington.” Newspaper editorials praised the city’s decision to accept the gift and spoke lavishly of the benefits for the people of Wheeling. One article extolled, “To summarize, Wheeling now owns 750 acres of unexcelled farmland, 65 buildings, including the big mansion, clubhouse and office building, miles of surfaced driveway, and a farm containing 700 species of trees and shrubs.” Clearly, the writer was impressed and felt strongly that the people of Wheeling should be as well. Another piece croons, “Wheeling should thank her stars that she has had such splendid citizens who have lived with a thought for her future and provided for it.”

In fact, the weight of the acceptance of Waddington for the future prosperity of Wheeling and the surrounding areas was a significant trope throughout the coverage of the decision. As one writer in the Wheeling Register noted, “Wheeling council last night made history — history that will live over the years to come — by formally and officially accepting, on behalf of the city, Oglebay Park, the gift of Col. Earl W. Oglebay, deceased.” These prophetic voices pointed to a legacy that continues to thrive nine decades later.

Oglebay Park at 90

July 2018 marks the 90th summer Oglebay Park has been owned and operated by the City of Wheeling. Over those 90 summers, the people of the Ohio Valley have watched the park expand far beyond its original boundaries to become the fulfillment of Earl W. Oglebay’s wishes and his grandest dreams.

While waiting for the people of Wheeling to accept or reject Waddington Farm, Crispin Oglebay carried on his uncle’s work. He collaborated with the Agricultural Extension Division of West Virginia University to establish a demonstration program at Waddington Farm for public recreation and adult education. These early endeavors are the roots of what would become Oglebay Institute in 1930, the organization largely responsible for many arts events throughout the Ohio Valley.

In the 1930s the Works Progress Administration would help build the Crispin Center, which is home to Oglebay’s Pine Room, where events are held year round, including the annual Woodcarver’s Festival and the Festival of Trees. Just outside the Pine Room, park visitors can enjoy a refreshing dip in Oglebay’s spectacular outdoor pool. Recent updates to the pool include new chairs, umbrellas, an in-pool obstacles course and climbing wall, and Fountains of Fun — a splash pad for young and old alike.

Known from its early days for its impressive stables, Oglebay Park still maintains horses and provides riding lessons throughout the year. Other recreational activities include golfing, tennis, kayaking and paddle boating on Schenk Lake, skiing, sledding and so much more. Recently, the park has expanded its trail system and updated its playground, the Good Zoo, Wilson Lodge, the cottages and more.

None of this could be possible without the efforts of civic-minded Wheeling citizens then and now whose belief in Oglebay’s vision urged them to devote their time and money into making his gift a “park for everyone forever.” In “Oglebay: The People’s Park,” an article that appeared in the April 1943 issue of the National Municipal Review, Paul K. Morris writes, “The people of Wheeling play at Oglebay, generously give their personal services, and, above all, think of it only in terms of ‘our’ park.”

Come out and celebrate our park’s 90th birthday from July 27-29. It is the biggest bash of the summer and includes reduced or free admission to many favorite Oglebay activities, homemade ice cream, a 5K walk/run, pedal boat races, live music, fireworks and more.

For a complete itinerary of Oglebay Park’s 90th birthday celebration, visit https://oglebay.com/90th-birthday-schedule-of-events/.

(Photos provided by Ohio County Public Library, Oglebay Institute and Oglebay Park.)