Baseball is back in full swing for the season, and many of us are ready to take to the field or root for our favorite team as fans. While “America’s favorite pastime” has fostered interesting stories across the country, from bustling cities to small towns, few remember that the first historian of Black baseball hailed from the Ohio Valley.

Baseball Beginnings in the Ohio Valley

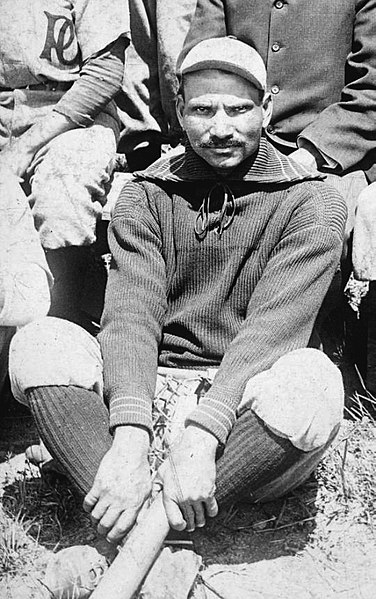

King Solomon “Sol” White was born right across the river from Wheeling in Bellaire, Ohio in 1868.1 While baseball as an amateur game had been evolving for decades, the first professional American baseball games were played right after the Civil War.2 During the end of the 19th century, as Sol White came of age, baseball started to take hold in the Ohio Valley.

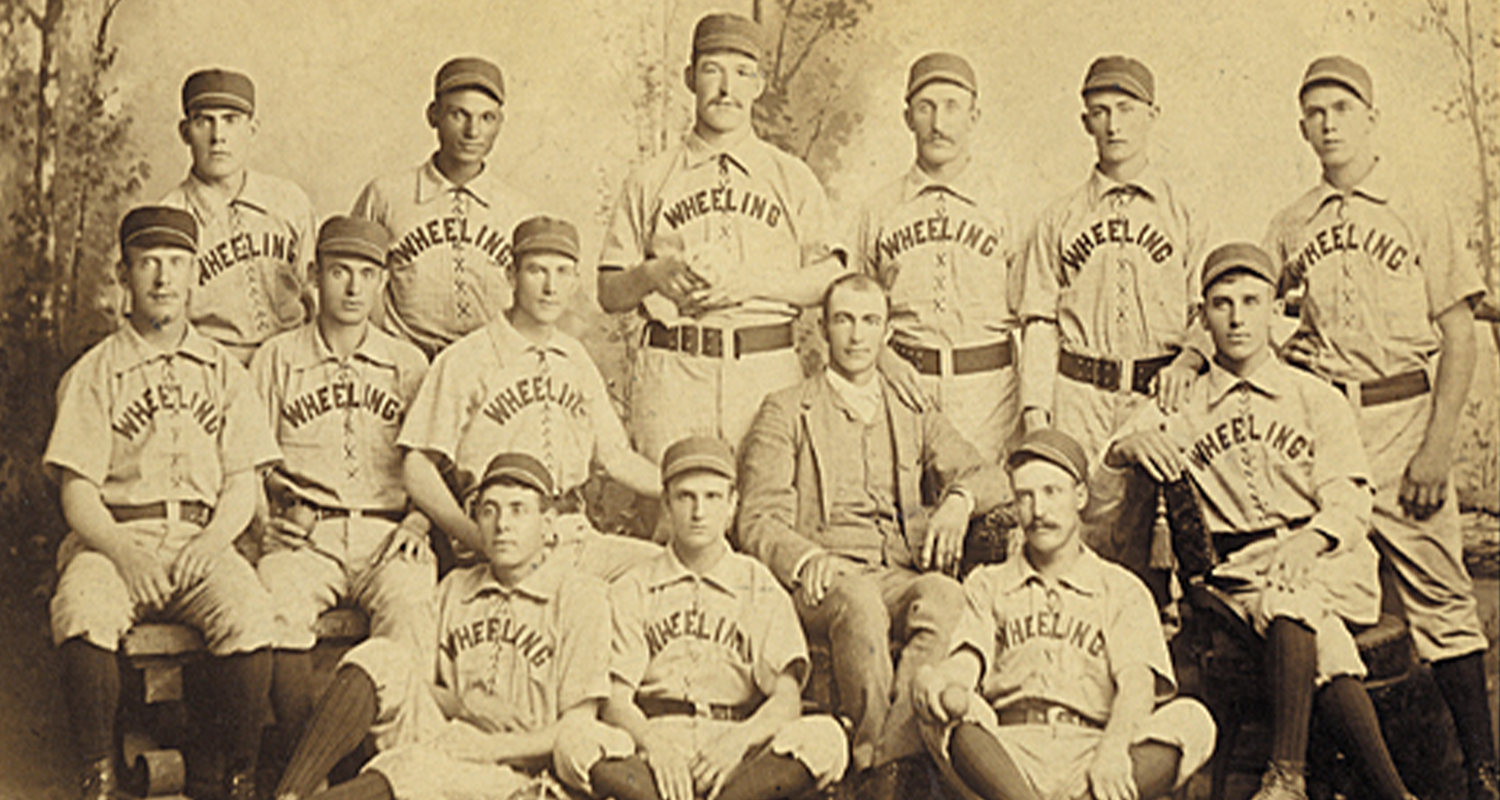

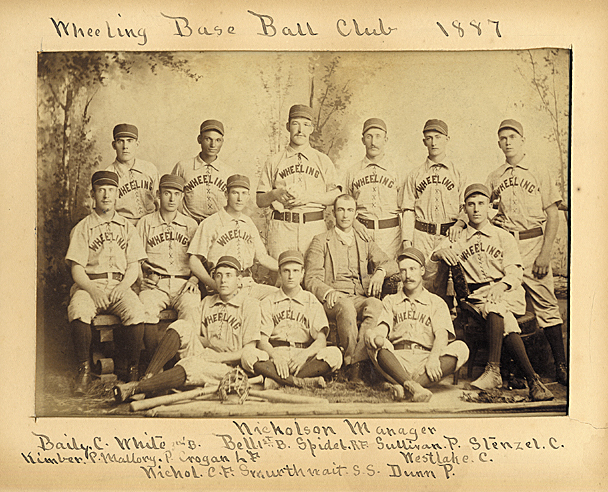

Little is known about the details of his childhood, but White grew up playing baseball on various fields around the Ohio Valley, with the biggest games occurring at Wheeling Island. He played for the Bellaire Globes and briefly for the Pittsburgh Keystones in 1887, before the team folded within a week.3

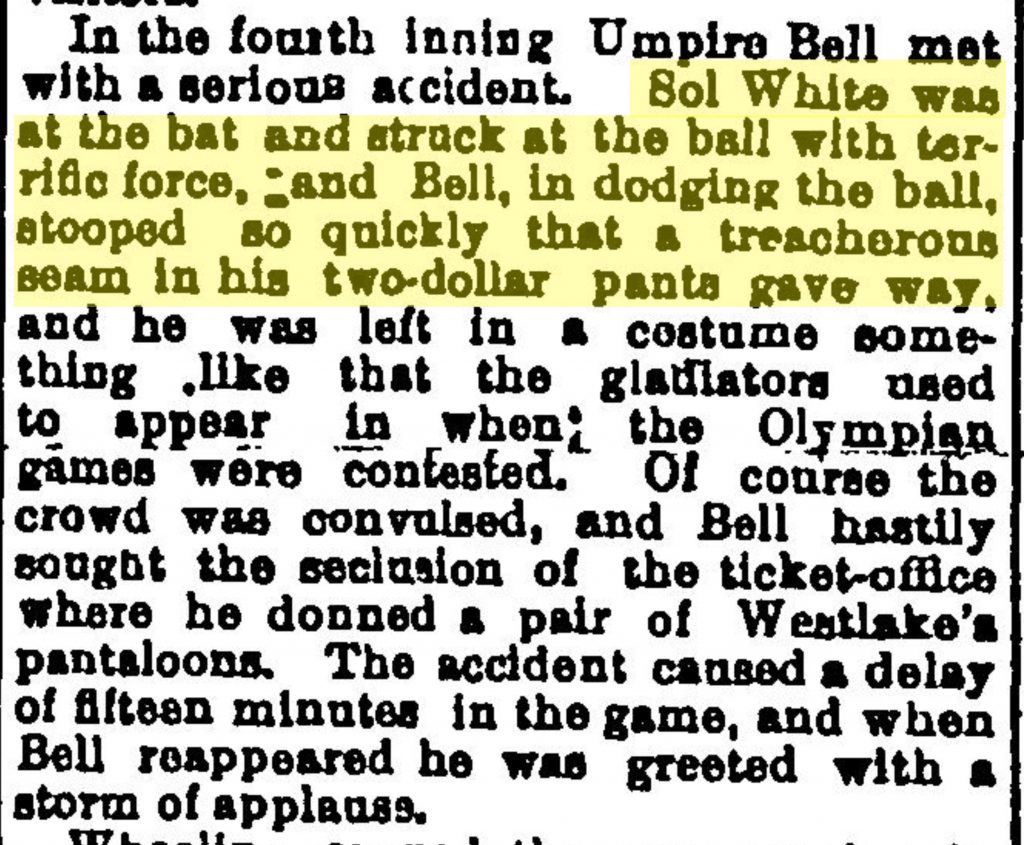

White then transferred over to the Wheeling Green Stockings—named after the team’s distinct green socks. His skill was quickly realized and shortly after his debut, the Island hosted a record-breaking 7,000 fans.4 While playing for Wheeling in the Ohio State League, White was in fifty-two games, hitting .370.5 Throughout his whole career, White was almost always described as a phenomenal player; in fact, in one game in Wheeling, he was up to bat and hit the ball so hard that the umpire had to dodge the ball and “stooped so quickly that a treacherous seam in his two-dollar pants gave way.” The game was delayed for fifteen minutes as the umpire frantically replaced his torn pants.6

Even though White only stayed with the Wheeling Green Stockings for a year, he made an impression. When White returned to Wheeling the next season, this time playing for a different team, Wheeling fans gave him a bouquet of flowers before the game.7 Decades later, the Wheeling Intelligencer still sang Sol White’s praises, naming him “one of the greatest ball players on the diamond today [who] has a large following of fans in every city.”8

The Rise of Black Baseball

In the late 1800s, there was a brief period of time where a few Black players were playing on predominately white teams, including in the Major Leagues.9 In 1887—the year White joined the Green Stockings—thirteen Black baseballers played across twelve different white minor league teams in the East and Midwest.10

However, as Jim Crow segregation became increasingly instituted in the late 19th century, racial discrimination quickly caught up with baseball. According to Jerry Malloy, prominent researcher of the history of Black baseball, “it seems clear that a majority of professional baseball players in 1887, both Northerners and Southerners, opposed integration in the game.”11 Segregation in baseball, north and south, became unofficially instituted.

During the early 20th century, excluded from the National and American Major Leagues, Black players, managers, and owners formed several of their own “Negro Leagues,” in various regions all across the country.12 According to The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, located in Kansas City, Missouri, the leagues of Black baseball teams “maintained a high level of professional skill and became centerpieces for economic development in many black communities.”13

While Sol White played briefly for the predominately-white team, the Wheeling Green Stockings, he spent the majority of his career playing and managing Black teams. White played for numerous teams, such as the New York Big Gothams, the Cuban Giants, the Page Fence Giants, and the Cuban X-Giants. In 1902, he helped create the Philadelphia Giants, a team which he played for, managed, and co-owned.14 The Philadelphia Giants became one of the strongest Black baseball teams, winning 86% of their games in 1906.15

It’s not entirely clear when White stopped playing and fully transitioned to managing teams, but it was probably in 1909 or 1911, when he was in his 40s.16 Throughout the 1910s and 20s, White managed numerous teams on the East Coast and the Midwest.17

Major League Baseball started to desegregate after Jackie Robinson famously played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. At the time, the moment was seen as a celebration of racial progress, however, as more Black stars began getting signed to the (formerly white) Major League teams, the Negro Leagues quickly disintegrated.18 Many Major League executives did not view the Negro Leagues as legitimate and therefore did not compensate the Black teams they took players from.19 Some teams lasted into the 1960s, but the last Negro World Series was hosted in 1948.20

Sol White, the Historian

While the Negro Leagues have been receiving more attention and study by historians and the baseball community in recent years, there was little motivation or support to document or retain official records or history during their tenure. Luckily, in addition to his stellar career as a player, manager, and owner, Sol White documented Black baseball’s early history…little did he know it would become crucially important.

During the off-season, for four winters starting in 1896, Sol White attended Wilberforce University, a historically Black university. White served in the Corps of Cadets and studied English—perfect academic preparation to write his history of Black baseball.21 In 1907, White published his Sol. White’s Official Base Ball Guide: A History of Colored Base Ball. It has been described as an “engaging pastiche of history, lore, instruction, and even poetry.”22 With his diverse experience as a player, manager, and owner, White was in the unique position of illustrating how the teams and leagues were formed, who the best players were, and how the Black baseball culture developed. The Guide includes pages and pages of photos of players and other important people that had influenced the Negro Leagues.

Sol. White’s Official Base Ball Guide not only chronicles the history of the first few decades of Black baseball, but also describes the racial discrimination and segregation that players would experience. For example, White compares how when his team, the Cuban Giants, played in Wheeling in 1887, they were hosted at the McClure House, a prominent hotel at the time. Yet, a mere two decades later when he writes the book, “the situation is far different today” and the Black players “[suffer] great inconvenience, at times, while traveling.”23 In addition to discrimination while traveling, White also makes sure to note the pay gap between Black and white players. In 1906, according to White, “the average major leaguer made $2,000.00…while the average black netted only $466.00.”24

Jerry Malloy considered Sol White’s Guide “the Dead Sea Scrolls of black professional baseball’s pioneering community.”25 Because the white Major League Baseball community did not view the Negro Leagues as legitimate, the states and events were not recorded or archived as systematically. However, as recently as December 2020, Major League Baseball formally decided to include the records of the Negro Leagues, recognizing that their quality of play was equal to the segregated Major Leagues.26 Researchers, historians, and baseball enthusiasts, in large part, have Sol White to thank for capturing the early (and almost lost) history of Black baseball.

Remembering Sol White

Sol White died in 1955 at the age of 87 in New York. While there is little documentation, White was married in 1906 to a Florence Fields from Philadelphia; one of their children, Marion, lived into adulthood. However, it appears that Florence and Marion largely lived apart from White as he traveled around the country for baseball.27 Despite his prominence and influence in baseball, White was buried in a pauper’s grave with eight other individuals in a vertical communal grave.28

For over half a century, White’s grave went unmarked, essentially unknown. In 2012, his final resting place received a proper gravestone as part of the “Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project,” whose mission is “to provide proper grave markers for players of the Negro Leagues to honor their contributions to history and the game of baseball.”29

During his last decade, White lived to see the color line of Major League Baseball broken when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947—when White was 79. Almost fifty years after he died, White was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame—the only inductee who played with a professional team from Wheeling.30 The racial segregation of Major League Baseball was created and dismantled within the lifetime of one of baseball’s finest, Sol White.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 Bill Francis, “Sol White Helped Change the Face of Baseball,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed April 9, 2021, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/short-stops/sol-white.

2 “Baseball History, American History and You,” The National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed April 15, 2021, https://baseballhall.org/baseball-history-american-history-and-you.

3 “Sol White,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed April 9, 2021, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/white-sol.

4 William Akin, “Black Player Keyed 1st W. Va. Pro Team,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, June 25, 1987, p. 23.

5 Jerry Malloy, “Introduction,” in Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball (with other documents on the early Black game, 1886-1936, Sol White, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), xxiv.

6 “Canton Captured,” Wheeling Intelligencer, August 30, 1887, p.1.

7 Akin, “Black Player Keyed 1st W. Va. Pro Team,” p. 23.

8 “Negro Giants Play Bellaire,” Wheeling Intelligencer, May 28, 1913, p. 7.

9 “Negro Leagues History,” The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, accessed April 15, 2021, https://nlbm.com/negro-leagues-history/.

10 Malloy, “Introduction,” xvii-xviii.

11 Ibid., xxi.

12 “Negro Leagues History,” The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

13 “Negro Leagues History,” The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

14 Francis, “Sol White Helped Change the Face of Baseball.”

15 Jerry Malloy, “The Strange Career of Sol. White, Black Baseball’s First Historian,” in Out of the Shadows: African American Baseball from the Cuban Giants to Jackie Robinson, ed. Bill Kirwin, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, 2005), 62.

16 Ibid., 69.

17 Jay Hurd, “Sol White,” Society for American Baseball Research, accessed April 9, 2021, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/sol-white/.

18 Andrea Williams, “‘We Have No Right to Destroy Them,’” The New York Times, April 14, 2021, accessed April 15, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/14/sports/baseball/jackie-robinson-day.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur&fbclid=IwAR2fisGqIAMD1WoVNi4C8oX2kcZBEGYFA_4diwKSDJtjacn-TE-rlHJDPMQ.

19 Ibid.

20 Tyler Kepner, “Baseball Rights a Wrong by Adding Negro Leagues to Official Records,” The New York Times, December 16, 2020, accessed April 15, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/16/sports/baseball/mlb-negro-leagues.html.

21 Malloy, “The Strange Career of Sol. White, Black Baseball’s First Historian,” 70.

22 Ibid., 62-63.

23 Sol White as quoted in Jerry Malloy, “The Strange Career of Sol. White, Black Baseball’s First Historian,” 74.

24 Hurd, “Sol White.”

25 Malloy, “Introduction,” xv-xvi.

26 Kepner, “Baseball Rights a Wrong by Adding Negro Leagues to Official Records.”

27 Jim Overmyer, “Sol White’s Family, Lost and Found,” Our Game, The Official Site of Major League Baseball, May 26, 2014, accessed April 19, 2021, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/sol-whites-family-lost-and-found-1f43d500c82f.

28 John Thorn, “Baseball Remembers Sol White,” Our Game, The Official Site of Major League Baseball, May 12, 2014, accessed April 12, 2021, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/baseball-remembers-sol-white-678de625d3f8#.vaeov0bim.

29 Mark Stewart, “Project History,” Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project, accessed April 12, 2021, https://nlbgmp.com/about-us.

30 “Sol White,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed April 9, 2021, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/white-sol.