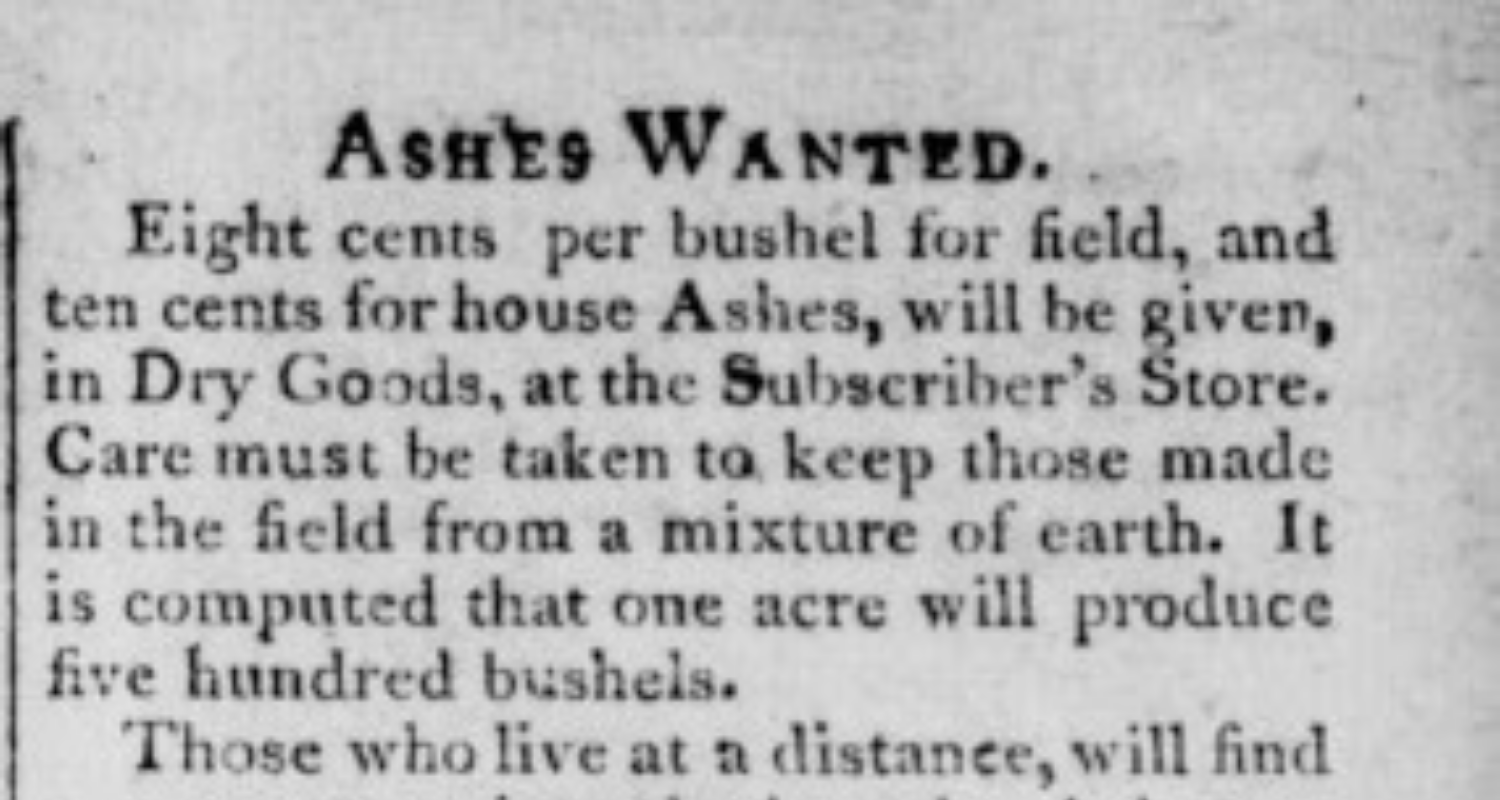

I’ve been spending a lot of time combing through Wheeling’s first newspaper, the Wheeling Repository. While looking for something else entirely, this headline caught my eye: Ashes Wanted.

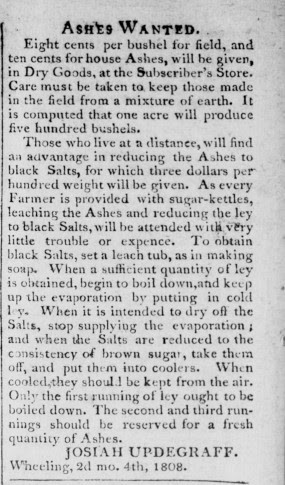

Ashes you say? Why would Josiah Updegraff be so keen as to pay for wood ashes? [1] And not just offer payment, but also include detailed instructions as to best reduce ashes into “black salts” for ease of transport.

The answer may lie in a few unusual places: baking, soap making, or glass manufacture.

Ashes in Domestic Applications

Wood ash is composed of 4% potassium, [2] and through a process of leaching, boiling, and refining yields a basic (opposite of acidic) substance called “potash” or “pearlash.”

Potash was essential for soap making and baking. In soap making, the potash was the chemical responsible for triggering the saponification process—turning oil into soap.

In baking, potash was used as a chemical leavening agent, meaning it helped baked goods rise. While baking soda and baking powder are more commonly used today, some traditional recipes like German Lebkuchen still call for potash [3].

Despite the importance of potash and pearlash for daily tasks, it was unusual for settlers to have their own personal ashery. Instead, they could collect and sell their ashes or black salts to local storekeepers like Josiah for “finishing.” [4]

Ashes in Your Glass

The tale of the glass industry in Wheeling is familiar to most—glass factories sprung up in the early 1800s due to the abundance of natural resources in the Ohio Valley. Beyond the plentiful supply of silica sand, glassmaking requires a flux – a material that when added to the “glass batch” lowers the temperature and viscosity thereby “thickening” the batch and making it easier to work with. [5, 6] What’s the flux in this situation? You guessed it…potash!

Although the first commercial glassworks in Wheeling was a window glass factory that opened in 1821 [7], it could be possible that a cottage industry of glass manufacture existed prior to industrialization.

Waldglas, or forest glass, was a type of glass manufactured in rural northern and central Europe from 1400 to 1800 c.e. This process relied heavily on wood for both the potash flux as well as fuel for the furnaces. [8] It was in this style that some of the earliest glass in North America was manufactured.

The demand for glass in England during this period, the depletion of forests and the lack of craftspeople encouraged the Virginia Company to pursue glassmaking efforts in their Jamestown Colony. One of the first exports from the Jamestown colony in Virginia was a “tryal of Glass.” Despite the ocean voyage, this product less costly than importing glass from continental Europe. [9]

Glass Demand

Advertisements for window and hollow glass from New Geneva, Pennsylvania ran in multiple printings of the Repository in 1807.[10] Additionally, a glass factory opened up in Wellsburg in 1815,[7] pre-dating any works in Wheeling by a few years.

While the true reason Josiah was seeking ashes remains unknown, we can assume the most likely answer is for domestic applications. However, it’s possible his ash-works could have supplied independent glassworkers in the area. Perhaps Josiah was on the cutting edge of this emerging industry.

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.

References

1 Wheeling Repository, February 4, 1808, accessed October 14, 2021 https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86092519/1808-02-04/ed-1/seq-6/

2 Griffin, Timothy S. Bulletin #2279, Using Wood Ash on Your Farm. University of Maine Cooperative Extension. PDF File. October 2004. https://extension.umaine.edu/publications/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2015/04/2279.pdf

3 The Spruce Eats. “Recipe Substitutions for Pottasche or Pearlash.” Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.thespruceeats.com/potash-and-pearlash-german-baking-aid-1446920.

4 Hazen, Edward. “The Agriculturalist.” In Popular Technology, or, Professions and Trades. (United States: Harper and Brothers, 1841) 26-27.

5 Corning Museum of Glass “Glass Dictionary: Flux.” Accessed October 14, 2021. https://www.cmog.org/glass-dictionary/flux.

6 Encyclopædia Britannica. “Properties of Oxide Glasses.” Accessed October 14, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/science/amorphous-solid/Properties-of-oxide-glasses#ref506683.

7 Ohio County Public Library. “Glass Industry in Wheeling in 1886.” Accessed October 14, 2021. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/2731.

8 Corning Musuem of Glass “Glass dictionary: forest glass.” Accessed 14 October, 2021. https://www.cmog.org/glass-dictionary/forest-glass

9 “Glassmaking at Jamestown – Historic Jamestowne Part of Colonial National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed October 7, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/glassmaking-at-jamestown.htm.

10 Wheeling Repository 26 March 1807 — Virginia Chronicle: Digital Newspaper Archive.” Accessed October 8, 2021. https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TWHR18070326&dliv=userclipping&cliparea=1.6%2C2276%2C3246%2C1145%2C757&factor=2&e=——-en-20-TWHR-1–txt-txIN-glass——-.