Editor’s note: In this series, we’ll talk to locals who struggle with autoimmune disease and share their stories. Below, Ohio Valley resident Michele Meeks shares her experiences with Multiple Sclerosis.

WHAT IS MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS?

WHAT IS MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS?

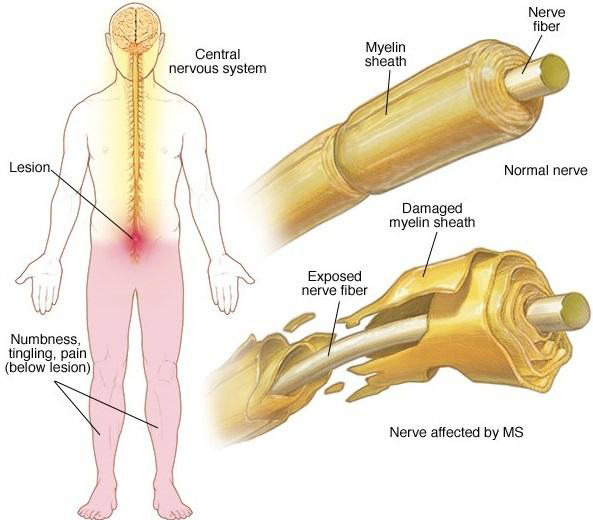

To help you understand her Multiple Sclerosis, Michele Meeks suggests picturing a wire, the kind you have running through your walls or to your appliances. It brings the electrical signal from the source to the destination, and it’s coated with plastic, for insulation. When that plastic coating is intact, everything runs smoothly. You flip a switch, electricity flows, and the coffeemaker goes on.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease in which the body attacks its own nervous system. Specifically, it attacks the myelin sheath, the insulation that coats and protects nerves that conduct impulses from the brain to the body.

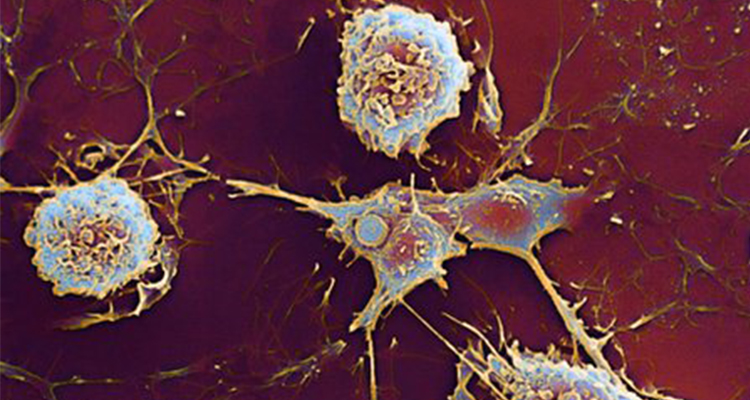

Next, imagine the plastic coating has been damaged in places or eaten away. The wires are exposed. Now, it’s a problem. Similarly, an MS patient’s immune system — specifically, the T-cells — has gotten confused and begins to attack the myelin sheath. Scar tissue forms at the site of the attack, and after the damage has been done, the nerve is never quite the same. The destruction of myelin triggers the symptoms of the disease.

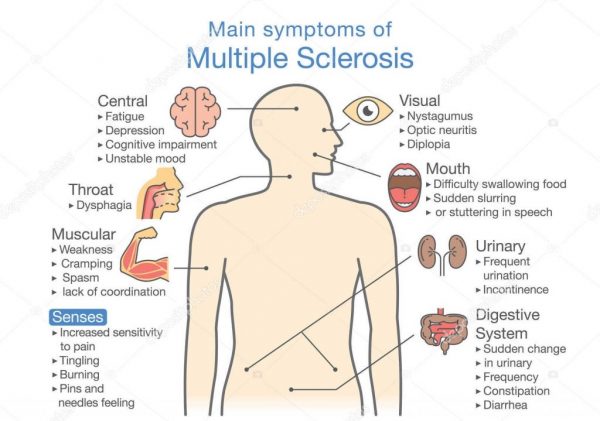

“Depending on how much damage was done on the nerves, and how big the scar is, it [determines] the functionality that you’re left with,” Michele, a Wheeling resident, explained. MS patients may deal with a host of symptoms, including fatigue, numbness, weakness, lack of coordination, pain, and bowel and bladder dysfunction.

“Depending on how much damage was done on the nerves, and how big the scar is, it [determines] the functionality that you’re left with,” Michele, a Wheeling resident, explained. MS patients may deal with a host of symptoms, including fatigue, numbness, weakness, lack of coordination, pain, and bowel and bladder dysfunction.

HOW IT BEGAN

“I was a senior in high school,” Michele said. “I was having issues in my right leg. I stepped down, and I would just collapse. I would be walking upstairs and trip. I wouldn’t lift my leg high enough, but I’d think I would be. And then I was having a hard time taking notes in school. I couldn’t get my fingers to hold a pencil.” She feared a brain tumor, as her grandmother had died from cancer. Her father assumed that her body was experiencing growing pains. Her mom and stepmom pushed her to see a doctor, who ordered an MRI. The scan revealed Michele had MS.

A neurologist verified the diagnosis. Testing revealed old lesions in her central nervous system that had been resolved. This indicated previous MS attacks, possibly long before her diagnosis in high school. Looking back, she can pinpoint times in her adolescence when those attacks might have taken place.

“I took ballet and gymnastics,” she said. “And right around 12-13, I got really clumsy. I couldn’t do it. In hindsight, the clumsiness and the lack of coordination was more from possible attacks.”

Michele’s parents raised her to be an independent woman. So when the symptoms of MS started inhibiting her freedom just as she reached early adulthood, she struggled.

“When they told me about this disease, I had to do all these special things. And I felt like, right when my world was opening up, they were like, ‘Oh, no, sorry, you can’t do that.’ And so I kind of rebelled. And I didn’t acknowledge it. I didn’t stay on treatments.” She pushed the diagnosis away, and pushed herself, too. She moved from her home in southern California to the Seattle area and began working, first as a loan officer and eventually a second mortgage supervisor.

She worked hard and didn’t get the rest her body needed. Consequently, it refused to cooperate. By 23, her MS began to accelerate. In addition to physical symptoms, she started experiencing emotional and cognitive problems. She forgot conversations she’d just had in a meeting. She also got overly-emotional about the clients she worked with, becoming too involved in their stories and breaking down in tears. And she needed excessive amounts of caffeine to combat her extreme fatigue.

“Being well-rested is huge,” Michele said. “I’d get home, and I wouldn’t even have the energy to take my work clothes off. I’d just pass out on the bed. It was kind of an awful existence in that I was just working and not doing anything else.”

Her doctor eventually encouraged her to take some time off from work and see if her body would function better without the stress of her job. Sometimes after an MS attack, the body bounces back to where it was before. Sometimes it does not, and the attack does permanent damage.

HOW MS AFFECTS HER LIFE

Michele’s difficulties often lie in repetitive motion. She can write only a few sentences before her hand stops working. Her limbs behave similarly. In a yoga class, for example, yogis often perform the same movements multiple times; by the end of class, Michele’s legs just don’t want to complete the task. When she’s holding a hot beverage, she often feels her hand begin to let go, and she has to concentrate on keeping her fingers around the mug. She’s not always successful. She said knives and pencils fly out of her hand or drop to the floor. Control often escapes her.

“It’s the repetitive use, the repetitive signal being sent,” she said. “It just slowly gets worse and worse. My leg gets heavier and heavier. If I kept pushing myself and not resting, it would just be dragging. So I have to stop and rest and then see if it’ll give me more. But there’s no way of knowing. I have a certain amount of steps I can take [each day]. And it’s very challenging, mentally, to be OK with that. Because you expect your body to do a certain thing.”

Like most autoimmune sufferers, Michele’s symptoms are invisible. Her worst day might not look bad at all from an outsider’s perspective.

“People see you and see a normal person,” she said. “There’s part of me that gets mad at that.”

Michele is on regular intravenous treatment that can occasionally have dire side effects. In addition, there’s always a chance her MS — the type known as relapsing-remitting — could morph into a more aggressive form of the disease. She doesn’t focus on those possibilities, though, because such worries aren’t helpful.

“I don’t play the what-if game. That’ll get you stressed out,” she said. Thus far, her treatment is going well.

WHAT SHE’S LEARNED

WHAT SHE’S LEARNED

“MS is a fascinating disease,” Michele said. Over the years and with the help of doctors and counselors, she’s studied her condition. She lives day to day, doing the best she can to stay positive. When she feels down, her symptoms seem to worsen in a mind-over-matter phenomenon. Fortunately, she has observed that connection and learned to use it to her advantage. Perspective is everything, and she spends her time working on her outlook and her body of knowledge.

“I realized that I had the opportunity that not a lot of people do,” she said. “They’re in a rat race, going to work and [having] a family, and they don’t get a chance to work on them. And so I started reading tons of books to try to figure out different ways to help me view the world that will make it more helpful. Because I realized that I need to have hope to go forward. Instead of, ‘This is being done to me,’ I’m changing the perspective. I have opportunities that a lot of people don’t get, and that is to try to work through issues they have inside as well. And it is hard.”

Michele now looks at the disease not as an attacker, but as something that’s a part of her, trying to survive. When her frustration begins to spin out of control, she finds it helpful to visualize her feelings as a group of individual entities. They used to sound like a group of toddlers running around in her head, but now, she doesn’t see them as wrong or ask them to stop, as that tends to backfire and make them stronger. During stressful moments, she acknowledges their presence but asks them to hold themselves in check until she can properly deal with them, whether it be through throwing something in anger or shopping or some other stress-relief technique.

“It’s this acceptance of how it is. Are you working with it or are you working against it? The more it wins, the more it rules you,” she said. This wisdom didn’t come quickly or easily. Michele has been working on her outlook for 20 years. Though at first, she felt like she was being punished, she no longer views her disease as malicious, and that realization took away a lot of the victim narrative she felt.

“It’s not about punishment,” she said. “You’re trying to live, and [MS] is trying to live, and how are you going to do it together? It’s like my hair. I have to brush it every day. It’s a part of me. And I need to take care of it. If I do, then it is nice to me, but if I don’t take care of it, of myself, then it’s not, at all. If I honor me, then it honors me as well.”

Honoring herself means staying on her medicine and resting — even in simple ways like making only one pass through the grocery store and foregoing items she’s forgotten or making a single trip up and down the stairs at home. It also means asking for help, which is never an easy thing for anybody to do. Autoimmune sufferers struggle with it because, most of the time, they technically can do it themselves. But in refusing to ask for help, they set themselves up for a crash or complications. Something as simple as a few extra moments in the store can mean a few days on the couch in a state of pain and exhaustion. These are difficult lessons to learn, but Michele honors that wisdom.

FINAL THOUGHTS

FINAL THOUGHTS

Michele has lived with Multiple Sclerosis for over 20 years now, and it’s been a difficult journey. But you’d never know it by talking to her. In the years since her diagnosis, she’s learned that she can either fight against the disease or fight for herself. That means respecting her body and its needs. She has goals for the future and a good sense of how to achieve them. Her understanding of MS and her peaceful acceptance of her body’s requirements have been hard-won, but she serves as an example of how we should all go forward with our limitations, whatever they may be.

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.