This lead plate is said to be about 11 inches long and 7-and-a-half inches wide, and according to preserved records one of the six claim markers Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville placed along the Ohio River during the summer of 1749 was near the mouth of Big Wheeling Creek.

And it could still be there, somewhere, likely buried from flooding that has taken place many times in the past 267 years or either accidentally uncovered, excused as debris, and discarded, or the records could be inaccurately interpreted. According to page 88 of The Céloron Expedition to the Ohio Country 1749, though, one of the plates could “possibly” have been installed in order for the French to claim the land that is Ohio and Marshall counties today. A 99-page English translation of the journals kept by Céloron during the mission was edited by Andrew Gallup and published by Heritage Books, and it offers much detail about Céloron’s experiences during the five-month expedition ordered by the governor of Canada, Comte Roland-Michel Barrin de la Gallissoniere.

“The expedition was conducted mainly to solidify France’s claim on the Ohio Valley and its many of the tributaries to the Ohio River,” explained Rebekah Karelis, historian for Wheeling Heritage. “It all started up in Canada; it was a long trip and went much further than here, and it included a lot of people.

“They placed the plates in order to claim the land, and they also nailed notices on a lot of trees, too, but as of today there are only a couple of them that have been found,” she continued. “The rest, I believe, have been lost unfortunately. The one that was supposedly here at Wheeling Creek has never been found. The only thing I have heard about it is that everyone has always been looking for it.”

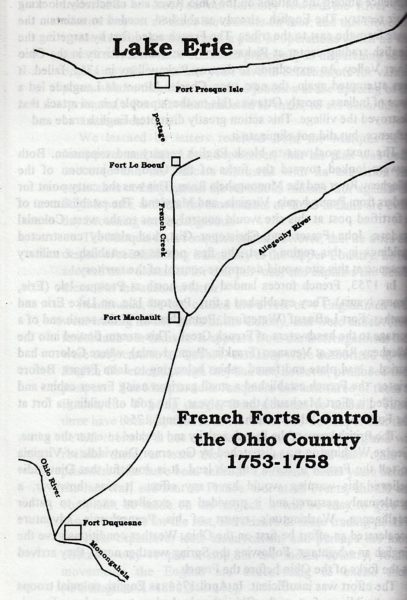

Yes, the goal was to stake the French claim to this region of the Ohio Valley, so Céloron departed Montreal with large boats, canoes, 216 French Canadians, and 55 Native Americans. Eventually the unit arrived to the Allegheny River, which then allowed them access to the confluence that creates the Ohio River in Pittsburgh. The mission called for Céloron to place the claim markers where he believed they were needed, and also the governor demanded all major tributaries to the Ohio River be tagged to remind the English settlers and Native Americans that they were trespassers and therefore criminals to French authorities.

The problem is that the Céloron Plate has never been discovered here in Wheeling.

“I’ve not learned of any organized hunts to find the Céloron Plate here in Wheeling, but I do know that people know about it, and they have talked about possible locations for it,” Karelis said. “The problem here is that since this expedition took place in 1749, there has been so much flooding that’s taken place since then, and that means a lot of silt has been redistributed in that area, and the ground has been moved there, too.

“I’m sure the early settlers knew about the plate in that area when they came here in the 1760s, but whether or not they left it there or they did something with it, we do not know. It’s really been lost in history,” she said. “If the one here in Wheeling was ever found, we do not know about it. The way the story goes, the plate was placed on the ground near a large tree on the southern side of Wheeling Creek, but the area has changed so much over the years that the tree they used isn’t there any longer.”

There are historical documents that have revealed this area was quite busy as the city of Wheeling grew with several different industries that operated in the vicinity of the tributaries opening to the Ohio River. Iron works, boat construction, and shipping ports are examples of such activity and of reasons why uncovering the plate could be an impossible task even today.

“But with the amount of historical discoveries that take place every day, I believe anything is possible as far as finding the Céloron Plate here in Wheeling, but unfortunately there would be some challenges because of Wheeling Creek and what was around that area through the years,” Karelis said. “You would find a lot of metal items and trash from the industries that were located there. At one time they even built steamboats along the mouth of Wheeling Creek there.

“That’s why it would really be challenging to find a lead plate, but with that in mind, we do have some pretty advanced technology these days. I know we now have metal detectors that can differentiate one metal to the next, but I do not know what more than 200 years would do to a lead plate that’s been under ground for that long,” she continued. “What would that look like after a couple of centuries? I don’t know, but it would be really neat to find.”

The expedition followed a combat conflict between Britain and France known as King George’s War, a battle centered around the region’s fur trade. The French believed they had claimed the region nearly 100 years before Céloron’s expedition, but the British had become solid allies with the Native Americans in the area, and colonies such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Virginia were angling for ownership, according to Gallup’s book.

“This area saw the French and Indian War before the Revolutionary War, and this expedition would have been leading up to those wars,” Karelis said. “The French and Indian War was essentially the French and the British fighting over North America, and the Revolutionary War was about 20 years later.

“We believe the early settlers discovered that this area was pretty special because of the success experienced by hunters and trappers at the time. It was all about survival at that time, and finding food in good supply was definitely a priority, and this area possessed a lot,” she continued. “That’s why, at that time, this area was contested over and over again.”

Celoron was born in December 1693 to parents Jean-Baptiste Céloron de Blainville and Helene Picote de Belestre, and he entered the French military in 1713 at the age of 19. If someone does find the plate he supposedly placed here in Wheeling, it could be identified by the French inscription said to appear on it. Translated by Gallup for his book, it reads:

In the year 1749, of the reign of Louis the 15th, King of France, we Céloron, commander of a detachment sent by Monsieur the Marquis de la Galissoniere, Governor General of New France, to reestablish tranquility in some Indian villages of these cantons, have buried this Plate of Lead at the confluence of the Ohio and the Chadakoin, this 29th day of July, near the river Ohio, otherwise Belle Riviere, as a monument of the renewal of the possession we have taken of the said river Ohio and of all those which empty into it, and of all the lands on both sides as far as the sources of the said rivers, as enjoyed or ought to have been enjoyed by the kings of France preceding and as they have there maintained themselves by arms and by treaties, especially those of Ryswick, Utrecht and Aix-la-Chapelle.

“I’m not sure if a worth could be assigned to such an item if the Céloron Plate was every found,” Karelis said. “And that’s because I do not think anything connected to the expedition has ever been sold. Without a doubt it would be a priceless object because of the history behind it and the meaning behind it, but there’s really nothing to compare it to. But it would be very special.

“It definitely would be a monumental discovery, though, because the Céloron Expedition was one of the first ones recorded in history the way this one was,” she said. “The 1750s is a time in Wheeling’s history that we really do not know a lot about because it’s shrouded in all kinds of myths and oral history more so than anything really concrete. That’s why, if that plate was ever found, it would be very special because it would tell us that it really did happen, and it really was placed here at Wheeling Creek.”

(Photos by Steve Novotney)