Editor’s note: In this series, Weelunk readers will meet their neighbors who are successfully navigating the road of recovery. Like any road trip, recovery has stretches of smooth highway as well as the occasional pothole. These are the stories of travelers who are making steady progress toward a better place, one day at a time.

To say that Mary Hess had a difficult childhood would be putting it lightly. She already was well-versed in neglect and other traumatic occurrences before she was out of elementary school.

To say that Mary Hess had a difficult childhood would be putting it lightly. She already was well-versed in neglect and other traumatic occurrences before she was out of elementary school.

Her family had financial, relationship and substance use issues at the Iowa farm where she spent her first decade of life. When she was 12, those issues culminated in her parents losing everything they owned, including the only home their five children had ever known.

THE ENDURING EFFECTS OF TEMPORARY TRAUMA

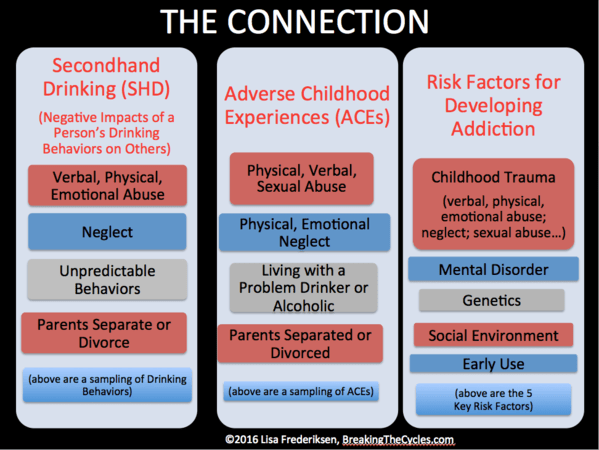

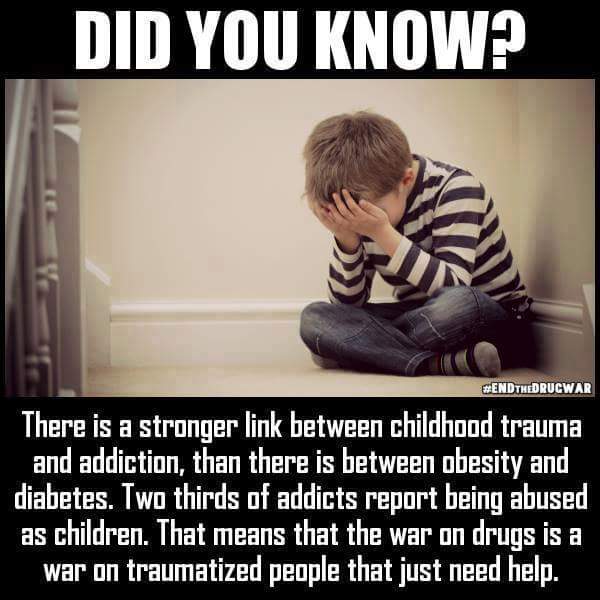

It’s a well-documented fact that traumatic childhood experiences can haunt us long after we’ve left childhood ways behind us. Studies show that children who experience one or more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are two to four times more likely to start using drugs and/or alcohol at an early age, compared to those who have not experienced childhood trauma. ACE test scores tally up various kinds of abuse and neglect that are indications of a difficult childhood.

Domestic violence, parental abuse or neglect and family substance use or incarceration are some of the factors that an ACE score takes into consideration. According to some studies, people with an ACE score of five or higher are up to 10 times more likely to experience addiction compared with people who haven’t experienced childhood trauma.

“The first few years of life are full of many important developmental milestones in terms of brain pathways, attachment, coping mechanisms and in general, learning how to relate to others and to stress. Those who experience trauma in their early years often develop survival mechanisms that are less than helpful in adulthood,” says Adi Jaffe, Ph.D., in a recent Psychology Today article.

It is not surprising then to learn that the adverse events of Mary’s childhood sent her straight down the path of substance use.

After the family lost the farm, Mary’s parents moved them to the inner city. At one point, they were homeless. Mary the farm girl was in a new middle school, trying to fit in with her peers in a totally unfamiliar city environment.

“Kids in the neighborhood began asking if I wanted to try this drug or that drug,” Mary says. “It was experimental at first.” She soon found herself using drugs and alcohol more and more frequently because that’s what her new friends were doing.

“Alcohol was always a big part of any family function on my mom’s side of the family,” reveals Mary. Drinking games to see who could drink the most and for the longest period of time were encouraged. Alcohol was readily available at home and in the neighborhood, so it, too, became one of Mary’s drugs of choice.

On more than one occasion while under the influence, Mary was sexually assaulted by boys in the neighborhood. She now recognizes that she was a victim of rape. “But at the time,” she says, “I thought that was how people expressed that they liked you.”

CONTINUED TRAUMA

Eventually, Mary’s father sent her to a youth shelter because her sister informed him that Mary had plans to go through a gang initiation. While she was at the shelter, Mary’s family moved yet again, as her dad realized that their inner-city neighborhood was detrimental to his children’s health and welfare.

After being discharged from the shelter, Mary joined her family in the new small town where they were living. But although the family’s location changed, the availability of drugs did not.

“Being the new kid yet again, I wanted to fit in,” Mary shares. “Kids would ask if I wanted a cigarette or drugs, and we’d get high at school. We often skipped school, and we partied every weekend.”

She said that like many kids, she received D.A.R.E. training in school. However, she says she felt a “complete disconnect” from the information presented in the program. When they discussed various drug-related scenarios at school, Mary says she didn’t recognize them as scenes that played out in her real world. Instead, they seemed more like some kind of Hollywood version of her experiences, which she says kept her from realizing that her drug use was a problem.

Eventually, Mary’s parents divorced, and her mother moved out of the family home. Her dad was now a single father to Mary and her siblings. Mary thought it would be a good time to drop out of high school and get a job to help her father. However, her intentions were twofold: yes, she wanted to help her family, but she also wanted to have money to buy her drugs of choice. She was now using alcohol, marijuana, crystal meth, cocaine and hallucinogens.

“Again, I didn’t see an issue,” Mary states matter-of-factly. “It was normal within my group of friends.” And besides, she says she felt like the fact that she was most assuredly helping her father financially made up for the reality that she was also “helping” to line the pockets of her local drug dealer.

But she certainly wasn’t helping herself. After about a year, her drug and alcohol use caught up to her and cost Mary her job. Her dad refused to allow her to move back home in her current condition; he was concerned that she’d be a bad influence on her younger brothers.

After a few months of couch-surfing with friends, she was able to talk her father into giving her another chance. But this time he was keeping a close eye on Mary, and it didn’t take long for him to discover that she was bringing drugs into his home. This time he gave her two choices — go to rehab, or he would call the police and turn her over to them.

At 17, Mary opted to go to rehab to avoid legal trouble.

THE FIRST STEP AND RELAPSE

But mostly, “rehab just introduced me to new people to use with there,” Mary remembers. At intake, the counselor diagnosed Mary with High Dependency Drug Disorder or, as we know it now, Substance Use Disorder. At the time of this diagnosis, Mary was the youngest person that her counselor had ever diagnosed with this disorder. She was introduced to Narcotics Anonymous and began half-heartedly working the 12-steps toward recovery. However, she was living a dual life of faking her sobriety while continuing her secret drug use.

While still in outpatient treatment, she began studying for her GED diploma. Mary maintained a high grade-point average and received her GED before she turned 18.

One day, Mary recalls, she experienced a “moment of desperation” when she felt totally lost and overwhelmed by the life choices she had made. She hatched a plan to leave Iowa altogether and escape to someplace new where she didn’t know anyone. Mary talked to her dad about her plan, and he was supportive. Together they found a college near Chicago for Mary to attend, and she packed her things and moved east.

But her fresh start did not work out as planned. Instead of leaving her dual life behind in Iowa, Mary continued living it in two separate places. She made friends in Chicago who encouraged and enabled her drug use. In fact, Mary started transporting drugs between the big city and her small town back in Iowa and even began dealing drugs on a limited basis. When her first-semester grade report arrived, Mary was shocked to see that her college GPA was .75. She had always been an “A” student previously, and in her drug-addled mind, she thought she was still doing well in college despite her substance use.

At about this same time, Mary began dating a man who was not a drug user. She was extremely careful to keep her habit hidden from him and his well-to-do family back in Columbus, Ohio. Their relationship grew serious and, before long, Mary learned that she was four months pregnant.

“My two older sisters had each had two children removed from their custody,” she says. “I knew how awful that was, and I didn’t want it to happen to me. I remember thinking, ‘If I don’t stop what I’m doing, I’m going to lose my baby.’”

After all those years, her unborn baby’s welfare was finally the motivation that Mary needed to make lasting changes.

THE ROAD TO WELLNESS

THE ROAD TO WELLNESS

“I finally started getting serious about my outpatient rehab,” says Mary. She was concerned that she had continued using drugs for the first four months of her pregnancy, but she kept that fact secret from her daughter’s father.

“I eventually confessed the truth to him, but not before my daughter was born,” Mary says. When she finally did tell him, Mary led him to believe that her drug problem was a thing of the distant past.

The new family moved to Columbus to be close to the baby’s grandparents. Mary continued going to NA meetings for only a brief period after the move. “Sadly, I quit going shortly after I moved to Columbus. I felt shamed by my daughter’s father and his mother for being an addict. I had become ashamed of who I was. I channeled my focus on giving my daughter a better life than I had,” said Mary. Her daughter was born healthy and suffered no ill consequences from Mary’s prenatal drug use; she is eternally grateful for that.

After becoming a mom for the first time, Mary returned to work in the foodservice industry. She also began seeing a therapist to better deal with the ACEs that led to her substance use disorder.

LASTING CHANGE

In the 16 years since that time, Mary has remained clean. When she turned 21, she says she thought she could handle an occasional alcoholic beverage. “It’s what you do when you turn 21. It’s also a part of the foodservice industry,” she tells Weelunk. “It’s a way to unwind with coworkers after the restaurant closes at night.” However, she quickly realized that for her, alcohol led to temptation and poor decisions. She opted to give up drinking and has never looked back.

Eventually, Mary and her daughter’s father went their separate ways. She subsequently married a man from Wheeling, and they relocated to this area.

Today, Mary is the mom of three children. Her daughter is 16 and was recently inducted into the National Honor Society at her high school. “I’m so thankful that all she’s rebelled against so far is doing dishes,” laughs Mary. Indeed it seems that her daughter is worlds away from where her mom was at that same age. Mary also has two young sons who are 7 and 3.

Their drawings and art projects brighten the walls of Mary’s office at the Unity Center, where she has been the executive director for almost three years now. “I actually did not talk about my past openly until I started working here. Working here has advanced my own recovery. The support and unconditional caring that I see firsthand here has made me proud of who I was, and I am able to own where I came from,” Mary shares with satisfaction.

Mary says that her extended family is also proud of her journey toward recovery. “I am still in contact with my father and my siblings. My father and two of my siblings actually moved to Columbus. My family is very proud of how far I’ve come. I was actually the first of my siblings to graduate college. I was able to attend classes while working full time. It took me 12 years to finish my bachelor’s in business operations management.” Mary finally completed that degree in 2012 from DeVry University. She reveals with pride that despite the challenges, she managed to make the Dean’s List at DeVry.

Three years ago, Mary was working as a server at the Metropolitan Grill in downtown Wheeling. While she always enjoyed her work in the foodservice industry, she felt like she could be doing more with her life. “I thought to myself, ‘I’m not making much of a difference in the world after all I’ve been through and overcome,’” Mary shares.

She struggled with that desire but had no concrete idea where to find the personal fulfillment for which she longed. One day, she resigned from the Metropolitan on a whim. “I had no plan at all,” she says. “But there’s always a plan, whether we know it or not.”

Mary checked Craigslist shortly thereafter and saw the opening for her current position at the Unity Center. The rest is history, as they say. Mary has found her purpose guiding and encouraging others as they navigate their own paths through recovery.

WORDS OF WISDOM

What advice would Mary give someone who has just made the choice to stop using and seek recovery?

“Stick with it!” she says emphatically. “It’s a choice every day.” It’s not easy to cope with the emotions of early recovery, which is why it’s a time when relapse is likely to occur. “People think, ‘I don’t want to feel this’ or ‘I don’t want to remember that,’ she says. “I still get stressed and overwhelmed. There are moments where you have flashbacks; you’re triggered by a memory or a smell. But you keep making the choice to stay clean. Don’t ever let others belittle you or your progress,” she emphasizes.

Mary also recommends finding the path that’s right for you, as each person has different needs. “There’s not just one method to get through this, which is why the Unity Center offers many options. Everyone has to make an individualized plan.”

Once you’ve found what works for you for today, Mary suggests celebrating even the smallest success. “You have a bill to pay!” she says. That in itself is a “win” if you previously had bad credit. You have to stay home and clean house? That means you have a place to live! It’s all good when you’re successfully traveling the road to recovery.

“Look into the eyes of the broken-hearted. Watch them come alive as soon as you speak hope.” — TobyMac, Speak Life

• A lifelong Wheeling resident, Ellen Brafford McCroskey is a proud graduate of Wheeling Park High School and the former Wheeling Jesuit College. By day, she works for an international law firm; by night, (and often on her lunch breaks and weekends) she enjoys moonlighting as a part-time writer. Please note that the views expressed in her writing are solely her own and do not necessarily reflect those of anyone else, including her full-time employer. Through her writing, Ellen aims to enlighten others on causes close to her heart, particularly addiction, recovery and equal rights. She and her husband Doug reside in Warwood with their clowder of rescued cats, each of whom is a direct consequence of his job as the Ohio County Dog Warden. Their family includes four adult children, their spouses and several grandkids.