One hundred years ago today, March 10, 1920, many eyes in the nation were on West Virginia. A change was literally coming from across the country via a special train car in which a Wheeling native was traveling. This Wheeling native — Jesse Bloch — was about to help change the course of history.

THE WRONG SIDE OF HISTORY

Dr. Katherine Antolini, assistant professor of history and gender studies at Wesleyan College, spoke last week at Lunch With Books at the Ohio County Library to kick off the library’s Women’s History Month events. Her topic was how the ratification of the 19th Amendment — the amendment that gave women the right to vote — happened in West Virginia. She also talked about the many arguments against the ratification.

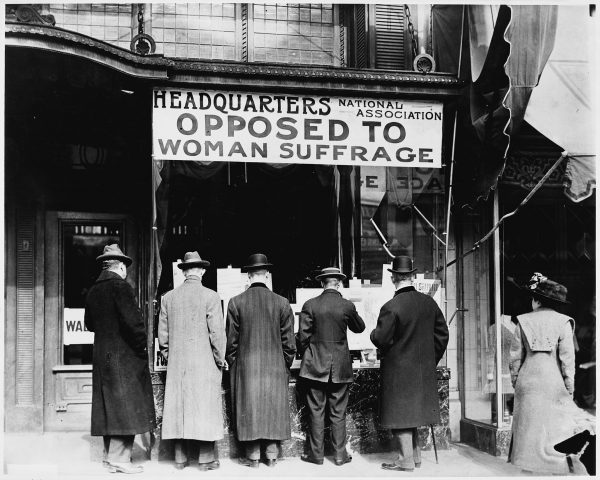

Antolini wasted no time in showing the audience just how strongly some men fought against the idea of women making choices at the polls that would affect their own lives.

One such man who did not hold back his contempt for the idea was West Virginia Del. Joseph Thurmond. He urged men to be courageous and do the right thing, for he believed keeping women from having the right to vote was in women’s best interest — that their honor needed to be defended.

“He was so adamant about his view that he hoped this is what he would be remembered for,” Antolini said. “This is from his speech on the House floor: ‘I want people to come by my grave and say, here lies a man who had the courage and the strength of character to vote against women voting.’”

Thurmond’s brazen belief was just one example of what the suffragists were up against. Violence was another.

Suffragists picketed at the White House for 18 months and were given the name the “Silent Sentinels,” because of their method of silently protesting with signs. Their protest was during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency and stood as a reminder in 1917 that Wilson did not, at that time, support the right for women to vote. The protesters were tolerated for a while, and then they began to be arrested on charges of obstructing traffic. Many went on hunger strikes in prison and were then subjected to being force-fed.

In November of 1917, what is known as the “Night of Terror” occurred when imprisoned suffragists were beaten after guards were ordered to brutalize the inmates — a very dark moment in women’s history in our nation. Women literally put their lives on the line for the right to vote.

LENNA YOST AND THE TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT

In West Virginia in 1916, suffragists mistakenly believed that winning over the state would be easy. The movement initially started in West Virginia in 1885 in Grafton, but it was slow moving. Suffragists began to think that the state was not ready for the idea of women voting.

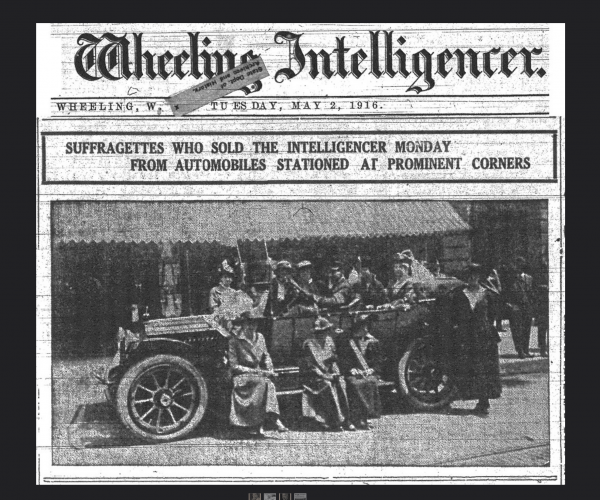

“Maybe it was just too new of a question in the state,” Antolini explained. “That West Virginia women are just not ready to organize … with the exception of Wheeling, West Virginia.”

Fairmont and Wheeling had early women leaders fighting for suffrage. The newspaper in Wheeling was more open to the idea than other newspapers in the state, which led to more printing of suffragist literature. Women began passing out pamphlets for their cause at fairs and other public events around Wheeling and Fairmont.

Lenna Lowe Yost was one of the early suffragist leaders who played a large role in getting the amendment ratified. Lenna was born in Marion County and later graduated from West Virginia Wesleyan College. Lenna married Ellis Yost, who became a state delegate. Ellis Yost proposed in 1913 to give women the right to vote, which actually passed the House but failed in the Senate.

“Women at this time were getting frustrated,” said Antolini. “Among those who couldn’t vote in West Virginia were ‘lunatics, idiots, felons and women.’ Women were getting a little tired of being categorized in that manner.”

As a couple, Lenna and Ellis gave the movement momentum with their joint efforts. At this time in our country’s history, prohibition and the temperance movement were underway, and the suffragists thought they could use it to their advantage. Lenna Yost became involved in, and eventually became president of, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in Morgantown. When Lenna also became a member of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association, it gave West Virginia a unique advantage over other states by having the same woman in charge of both organizations, and Lenna felt confident that the men who supported prohibition would also favor the right for women to vote.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) decided to donate funds to the campaign in West Virginia to help the cause. This resulted in organized speakers who would make their way around the state stumping to educate men and women about the movement and to encourage men to vote in their favor.

Despite their efforts, West Virginia overwhelmingly voted no in 1916, and it was a shock. The suffragists had wrongly believed that some of the things that held up the vote in other states would not be a problem in West Virginia — such as the anti-suffragists not becoming organized until 1916, whereas the suffragist movement had had a presence in the state for much longer. Also, regarding prohibition, West Virginia was already a dry state, so they did not think the liquor industry’s anti-suffrage beliefs would matter much.

Unfortunately, the counties that had voted for prohibition were the same counties that voted against suffrage. Lenna Yost was devastated, feeling that the indifference of other women was largely to blame for the loss. She eventually resigned from NAWSA after the failure of 1916 in order to focus her efforts more on the Women’s Christian Temperance movement in Washington, D.C. It wasn’t until 1920 and the drama of the ratification of the amendment in West Virginia that Lenna felt the calling to become involved again.

WHEELING AND THE SUFFRAGISTS’ ‘PAUL REVERE’

“We don’t think of West Virginia influencing national politics very much, but they really did,” Antolini explained of the ratification in 1920. The defeat in 1916 changed the way NAWSA viewed the whole campaign. Initially, they were focused on trying to win state by state. When West Virginia was such a huge loss, they realized that there was no way they would win over the rest of the south, and so began focusing their efforts on a federal level. The defeat of West Virginia influenced them to change their tactics, which led to the topic being debated in Congress on a national level.

In 1918, the amendment passed the House and then went through the Senate in 1919. By December of 1919, the amendment was ratified by 22 states; 36 were needed for it to pass. West Virginia senators were not scheduled to meet, however, until after the 1920 presidential election.

By this time, President Wilson announced his support for women’s right to vote, which was a huge move for the cause, and he hoped it would get him re-elected in 1920.

If West Virginia wanted to be included in this ratification, they would have to hold a special session — a session held outside of regular meeting times — to vote. When it became apparent that West Virginia would have a role to play again, Lenna Yost came back on board and agreed to lead the Ratification Committee with hopes of fixing the loss she endured in 1916.

President Wilson was sending telegrams at this point asking senators to get on board with the amendment, putting pressure on those in opposition, while women were having “live petitions” — greeting senators in Charleston face to face — to prove that, yes, women really do want the right to vote. A live petition was much harder for someone to ignore, unlike a paper petition that one could just throw away. Lenna felt it was extremely important to get women in front of the men who would be voting.

On March 3, 100 years ago, the vote passed in the House but was blocked in the Senate in West Virginia.

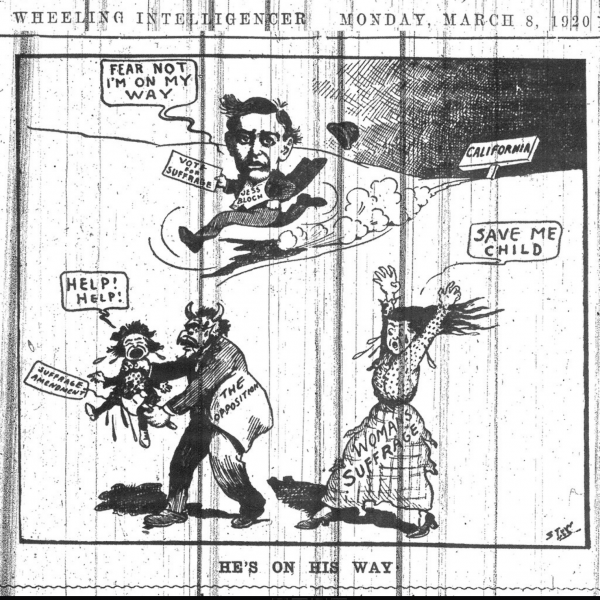

And that’s when Wheeling native and West Virginia senator Jesse Bloch stepped up to the plate.

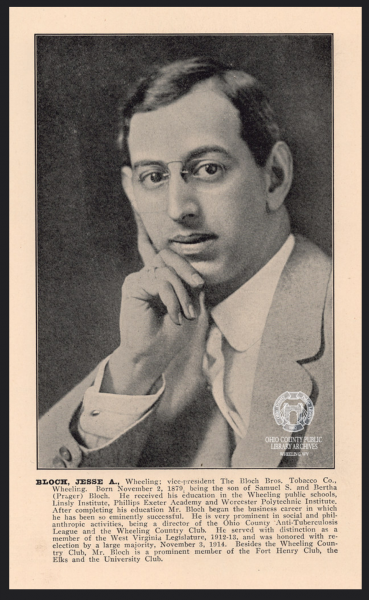

Jesse Bloch was the son of Samuel and Bertha Bloch, and Samuel was the president of the Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company, located on Water Street in South Wheeling. Bloch Brothers Tobacco became famous for its sale of Mail Pouch Tobacco, whose ads were a familiar sight on barns across the state.

Jesse Bloch served as a member of the House of Delegates in the 1910s and then became a senator in 1920. When the special session was called for the ratification of the 19th Amendment, Jesse was vacationing across the country in California.

When the vote tied 14-14, it is believed that Jesse was reached in California by telephone. Jesse was in favor of women’s suffrage and needed to get back to West Virginia — 3,000 miles away — to cast his vote.

A special train car was ordered to get Jesse to his destination. Some of the rumors regarding this trip claim that Jesse jumped on the train in his swimming trunks as soon as he heard. Whatever he was wearing, the country took notice of a senator from Wheeling, West Virginia, trying to beat the clock to help women win the right to vote. Newspapers even reported his passage through certain parts of the country so those following the story would know where he was.

While Jesse was trying to get home to the West Virginia hills, Lenna Yost and the suffragists had to make sure they could keep the 14 who had voted in favor of the ratification in session. They had to keep track of each senator so that when Jesse arrived in Charleston, all the men would be present for the conclusion of the session.

It took Jesse three days to get home from California, via Chicago, Cincinnati and finally Charleston. It is said that he initially wanted to fly across the country, but his wife refused and said they would take a train.

Stories regarding these three days include the suffragists peering into local shop windows in Charleston to make sure they knew where their senators were, and even making one senator come down from a ladder at a construction site to make sure he was ready for Jesse’s arrival.

Members of the opposing side tried some tricks of their own, trying to get a senator who had resigned in 1919 back on board to tip the vote in their favor, claiming he had never truly resigned. However, his resignation letter was found and proved that he could no longer vote. The opposition also spread the idea that Jesse might be kidnapped along the way, trying to scare him.

However, Jesse arrived in Charleston to cheers and a standing ovation to cast his vote. One member of the opposing side, once realizing Jesse’s arrival meant women would be granted the right to vote, quickly changed his vote to be on the right side of history, thus making the final vote 16 to 13 to ratify the amendment.

Jesse spoke to a reporter in Charleston and the following quote was printed in the Charleston Gazette: “I am glad that I will have the pleasure of casting my vote for the suffrage amendment and also to praise the 14 fellow members of the Senate who have stood together solidly to hold the special session together until my arrival. It is they that deserve the credit for any good that may come of my vote because it was only the courageous stand taken by them that made it possible for my ballot to be counted.”

On March 10, 1920, West Virginia became the 34th state out of the 36 needed to ratify the Amendment. Once West Virginia was won, suffragists knew they would succeed.

One hundred years later, 2020 is a presidential election, and we have the right to cast a vote this November, thanks to our ancestors who fought relentlessly for years and put themselves in danger for what they believed was right for women and for the nation as a whole. We have come a long way in 100 years, but it’s easy to draw a comparison of the fight for the right to vote with more modern fights of today, such as equal pay for women and the #MeToo movement.

In the last five years, we’ve seen two women run for president or presidential nomination, coming closer than any women have before them, only to watch them lose — maybe because the belief still runs strong that the president is a man’s job, similar to the belief that voting was a man’s job.

In 1920, however, it would have been unheard of for women to get so close to being elected to office. The country still has a long way to go with gender equality, but on election day this November, Wheeling should feel proud that we had a small role to play 100 years ago with our native son’s race to be on the right side of history. We should remember to take a second to silently thank all the women and men who made that possible — especially the ones from our little town of Wheeling.

BLOCH’S RIDE

By May Stranathan

Originally published in the Pittsburgh Dispatch of March 12, 1920

Up from the ground at break of day

Where wires were pulled to block delay,

Came news that fell with a sickening thud,

That the anti-suffs were out for blood,

And the woman voter’s name was mud.

And fierce the battle raged all day,

And Bloch was 3,000 miles away.

But over the wire flashed Charleston’s fate,

Far to the land of the Golden Gate;

Till word of the women’s direful plight

Reached the ears of their far-off knight,

He tarried not for the morning light,

But mounted his iron horse of speed,

Which snorted and puffed like a living steed,

And the enemy learned in wild dismay,

Bloch was only 2,000 miles away.

Across the Continent on they sped,

And plains and mountains behind them fled;

And when a moment’s pause they make,

The Senator asks for tea and cake,

As cool as if there’s not at stake,

Freedom for women in this day,

And Bloch 200 miles away.

Then into Charleston town he rides,

And up the Capitol steps he strides;

As courtly a figure as e’er drew lance,

For womankind while chargers prance,

In days when knights were bold and free;

None more triumphant came than he,

And none were welcomed more joyously,

Than Bloch, when from thousands of miles away,

He came for women to save the day.

• Kelly Strautmann lives out in the country of Cameron, West Virginia, and proofreads in the city of Wheeling. She has a supportive and talented husband and two ridiculous daughters who keep her busy and full of love.