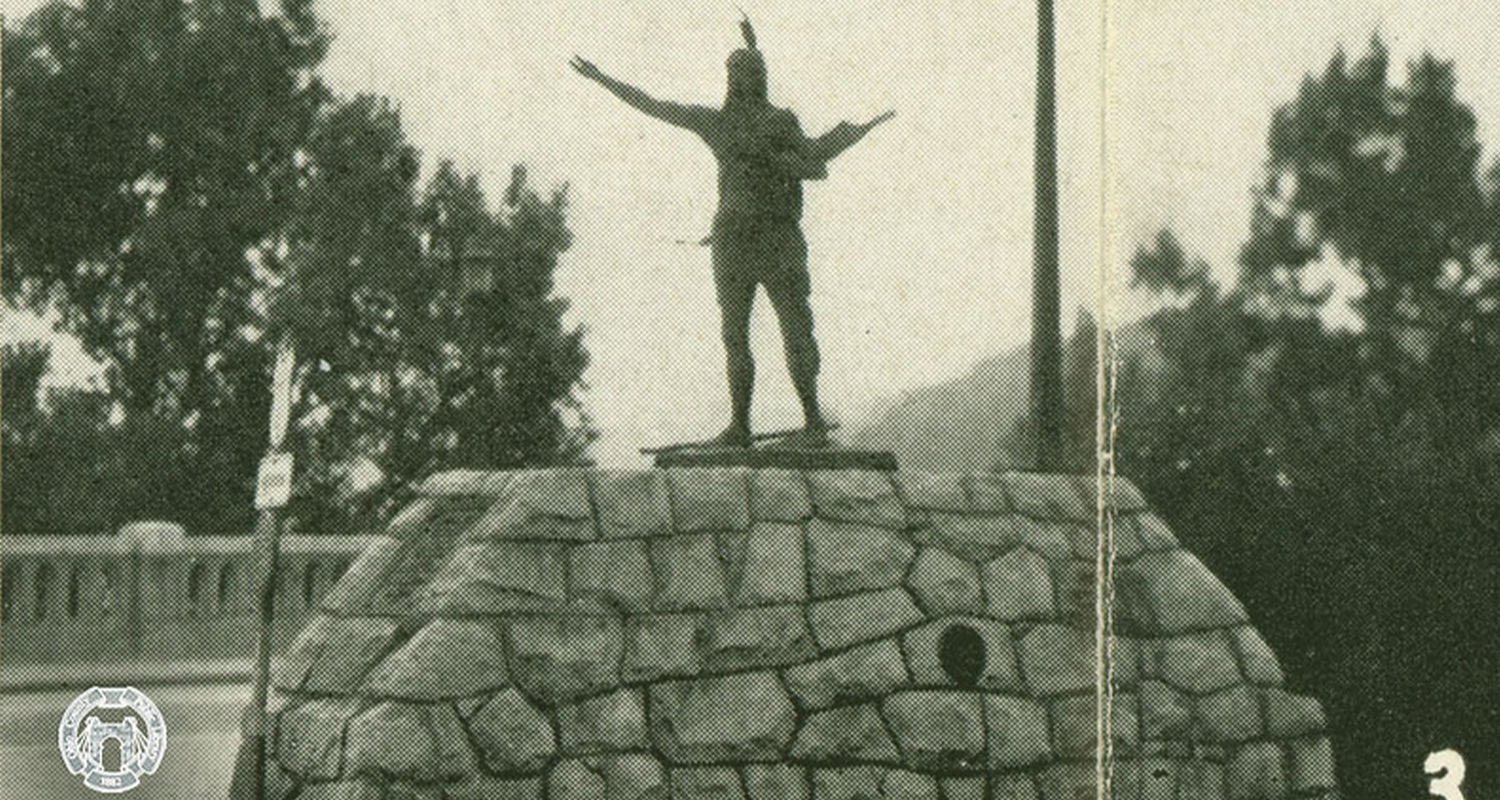

The Mingo statue has long been a recognizable landmark on Wheeling’s landscape. It has been featured on the cover of tourism brochures and included in the Smithsonian Art Inventory. Recently, it has even been updated to adhere to COVID-19 mask regulations![1]

Origins of the Statue

The idea and motivation for the statue came from George W. Lutz, a well-regarded leader in the Wheeling community known for his civic improvement projects, and was funded by the Wheeling Kiwanis Club. The statue was designed and sculpted by Wheeling resident, Henry Oscar Beu, who worked for the North Wheeling Pottery Company. According to Beu’s daughter, Bertha Ritter, it was “the biggest project he ever made.”[2]

The statue was dedicated on June 21, 1928 and the festivities included a parade that started at the McLure Hotel in downtown Wheeling and “marched up Market street to Tenth, then up Tenth street to the extension and over the hill,” a distance of about a mile. The parade was mostly made up of members of the Kiwanis Club, led by the Fort Henry Band. In his speech at the dedication, Lutz declared that “there is nothing on this statue to deteriorate and it will stand here forever to welcome travelers to our city and to commemorate the first inhabitants of the Ohio Valley.”[3]

The Meaning of the Monument

The inscription reads “THE MINGO. Original Inhabitant of this Valley extends GREETINGS and PEACE to all Wayfarers.” The Mingo statue was supposedly created as an homage to the indigenous peoples who lived in the area that is now Wheeling.

But the Mingo Tribe did not exist.

While the “Mingo” have been associated with the Ohio Valley and other parts of West Virginia, it was not a tribe, but rather a conglomeration of several different groups of indigenous people. It included members of the Delaware, Shawnee, Cayuga, Seneca and Mohawk peoples.[4] They originated as a section of the Iroquois Confederacy that broke away during the mid-18th century and migrated south towards (what is now) Ohio and mixed with other groups of people. Around the time that Ebenezer Zane started a European settlement in the area of Wheeling, indigenous people had a settlement around present-day Steubenville—only a short distance up the river.[5] Substantial historical people and events related to Wheeling have long been associated with the “Mingo.” Logan the Orator, a famous Cayuga war leader in the region, is often mistakenly referred to as a “Mingo” and the attacks on Fort Henry in 1777 and 1782 have long been attributed in part to the “Mingo,” among others.

However, remarks made at the 1928 dedication of the statue, which were published in The Wheeling Intelligencer, described a people who had been vanquished. Howard Matthews, the Kiwanis Club member presenting the statue to the city, stated that “today the Pale Face inhabit the shores and the Red Man is gone,” using common language of the time that is today, largely considered offensive. Matthews further emphasized this point at the end of his speech when he concluded that “today the Indians are driven out and cities have risen out of the wildernesses that covered the land.”[1]

What the speakers did not acknowledge is the long history of the removal of indigenous peoples from their lands in the United States, including the Ohio Valley. As European settlers claimed lands further west, the indigenous groups were pushed further into Ohio, to the Sandusky River. Under US Indian Removal policy, they were forced to leave Ohio and were relocated to a reservation in Kansas and then eventually, Oklahoma.[2] Today, the descendants of the “Mingo” are mainly part of the Ohio Seneca-Cayuga, who are included in the federally recognized Seneca-Cayuga of Oklahoma Tribe.

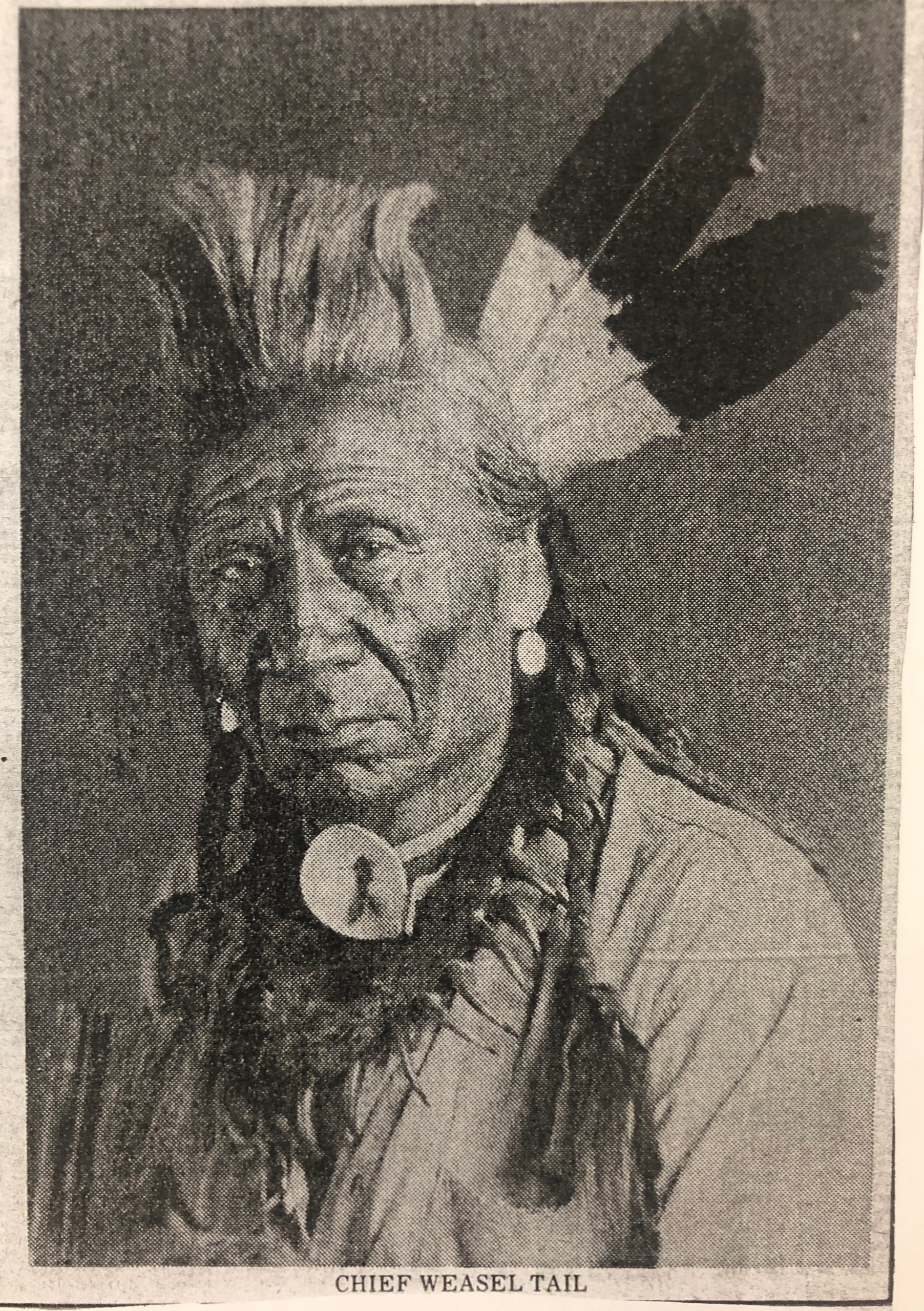

The one person at the dedication who did call attention to the oppression of indigenous people was an attendee from the Algonquin Tribe—Francis Valle Boyce or Running Bear, who said that he was “a descendant of the most downtrodden race in the history of the world. My tribe is struggling to rise once more to its former position.” In some Wheeling residents’ memories of the event, the attendance of indigenous people—like Running Bear or Chief Weasel Tail—was exciting, but also tokenizing. Thomas Foulk, who was a six or seven year old child at the time of the dedication, remembered decades later how “all the kids in the neighborhood were fascinated with [Chief Weasel Tail], with being able to see a real Indian.”[3]

The Kiwanis Club, the fraternal organization that financed and organized the Mingo statue in Wheeling draws its name from a Native American expression “Nunc Kee-wanis,” which according to the Kiwanis national organization website, loosely means “we trade.”[4] However, there is no indication that the national founders or the Wheeling chapter members were indigenous or had any ties to indigenous culture. The Wheeling Kiwanis Club has remained involved in the statue, leading its restoration in 2011 and routine maintenance.

Indigenous Representation in Wheeling

Largely due to the removal of indigenous peoples from their lands, West Virginia does not currently have any federally recognized tribes. Wheeling has a monument depicting the indigenous people who were once here, whose land the US federal government took from them, but too often we forget that indigenous people are still here today. According to the US Census Bureau, the city of Wheeling’s population in 2019 was approximately 26,430 people with an estimated 0.2% being “American Indian and Alaska Native.”[5] In comparison, after the 2010 Census, the US Census Bureau reported that 1.7% of the total US population was “American Indian and Alaska Native” alone or in combination with another race.[6] While 0.2% may seem like a drop in the bucket, that is about 52 people—52 people with lives, histories, and cultures.

Although indigenous peoples constitute a small fraction of the area’s population, pieces of their history and culture are scattered in plain sight across much of the landscape. The city’s own name, Wheeling, is derived from the Lenni Lenape or Delaware people’s word “weel-lunk” that has come to be translated as “place of the skull.” Other names, like the road names Erie St. or Ontario St. on Wheeling Island, originally come from various other indigenous languages.

The Statue Today

The Mingo statue has lived a colorful life. During the mid-20th century, it was occasionally used as a canvas for fraternity antics such as being hung with a sign reading “I am a Kappa Delta Kappa pledge,” or decorated with local high school colors for sporting events.

However, on January 29, 1982, the figure was cut at the ankles and carried away during the night by three men from Columbus, Ohio. The Wheeling police were alerted by an anonymous phone call and the three perpetrators—Robin McCoy, Antionello E. McCoy and George N. White—were arrested and the statue recovered. Almost immediately, several groups came forward and offered to fix the statue, but the task was eventually completed by George Macek, as one of his last projects before retirement from Mull Machine in Wheeling. It was rededicated on April 21, 1983.

The statue still stands at the location where it was originally placed, at the top of Wheeling Hill on the historic National Road. The figure has often been considered a welcoming symbol to the “Friendly City.” Hundreds of people drive by it every day on their way to work, school and errands. But how many residents of Wheeling, let alone visitors to the city, know the history of indigenous people in the area? Does the Mingo statue—one of the only visual representations of indigenous people in the city—adequately explain this history?

There is still so much research to be done and history and culture to be learned and respected in regards to the indigenous people of the Upper Ohio Valley. To start, you can learn more about the history of indigenous removal from the area with books like Land Too Good for Indians: Northern Indian Removal by John P. Bowes. To learn more about the Seneca-Cayuga Nation, click here to access their homepage. For more resources on indigenous history in the Wheeling area, click here. Just start somewhere.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “‘Masked Mingo’ Makes Appearance, Greets Travelers Atop Wheeling Hill.” The Intelligencer Wheeling News-Register. March 19, 2020. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.theintelligencer.net/news/top-headlines/2020/03/the-masked-mingo-makes-appearance-greets-travelers-atop-wheeling-hill/.

2 Bob Dunn, “Four Firms Volunteer To Fix Indian Statue,” The Intelligencer, January 29, 1982, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22mingo%20indian%20statue%22&i=f&d=01011920-10152020&m=between&ord=k1&fn=intelligencer_wheeling_news_register_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19820129_english_9&df=1&dt=10.

3 “Kiwanis Indian Statue Presented to City,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, June 22, 1928, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22mingo%20statue%22&i=f&d=01011928-10162020&m=between&ord=k1&fn=wheeling_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19280622_english_21&df=1&dt=9

4 “The Mingo, (sculpture),” Smithsonian Art Inventory, accessed November 3, 2020, https://siris-artinventories.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?session=B6C31A5100569.3776&profile=ariall&source=~!siartinventories&view=subscriptionsummary&uri=full=3100001~!310884~!0&ri=1&aspect=Keyword&menu=search&ipp=20&spp=20&staffonly=&term=mingo&index=.GW&uindex=&aspect=Keyword&menu=search&ri=1″>ntories&view=subscriptionsummary&uri=full=3100001~!310884~!0&ri=1&aspect=Keyword&menu=search&ipp=20&spp=20&staffonly=&term=mingo&index=.GW&uindex=&aspect=Keyword&menu=search&ri=1.

5 Travis Henline, “Native Americans,” Lecture, Wheeling, January 12, 2019, accessed November 3, 2020, https://wheeling250.net/program-videos/.

6 “Kiwanis Indian Statue Presented to City,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, June 22, 1928.

7 “Seneca Indians.” Ohio History Central. Accessed November 03, 2020. https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Seneca_Indians.

8 “Indian’s Visit Recalled,” The Intelligencer, February 3, 1982, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22weasel%20tail%22&i=f&d=01011928-12312000&m=between&ord=k1&fn=intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19820203_english_45&df=1&dt=4

9 “Our History.” Kiwanis. Accessed November 04, 2020. https://www.kiwanis.org/about/history.

10 “Quick Facts: Wheeling city, West Virginia,” US Census Bureau, accessed October 29, 2020, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/wheelingcitywestvirginia.

11 Tina Norris, Paula L. Vines, and Elizabeth M. Hoeffel, “The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010,” United States Census Bureau, 2012, https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/c2010br-10.pdf.