Editor’s note: Throughout Wheeling’s history, one aspect has remained a constant — the Ohio River. From the birthplace of the first western-style steamboat to laying claim to the Ohio River’s first suspension bridge to being a major shipping port of Wheeling-made goods to welcoming world-class river cruises — its claim to river fame are far too numerous to count. This occasional series will explore some of Wheeling’s most fascinating and unusual river history and the impact the river continues to have on the Friendly City.

What is it about maritime disasters that transfixes society? Even more than a century later, the sinking of the White Star liner Titanic in 1912 still captivates attention and interest. The idea of a grand ocean liner slipping beneath the waves of the icy North Atlantic with a great loss of life is so unnerving — yet gripping.

But before the Titanic disaster became a household name in the United States, another disaster of a different kind gained notoriety nationally.

In the late Victorian period, excursion steamboats were a popular thoroughfare for many Ohio Valley residents who sought a quick getaway or outing. Families would rise early and head for the wharf where hundreds would be queuing to board a paddlewheel steamboat with belongings and picnic baskets in hand.

A normal outing would depart before 7 a.m. and pick up more passengers along its way, oftentimes by simply nosing into the shore to answer the hail of a group of would-be excursion seekers. One such vessel was the side-wheel steamer Scioto, which was chartered by the Wellsville Cornet Band to take passengers on a roundtrip Fourth of July excursion from East Liverpool, Ohio, downriver to Moundsville, West Virginia.

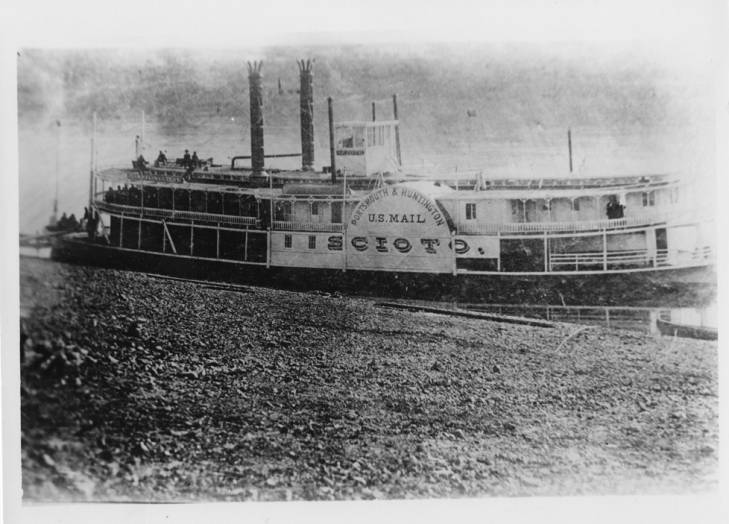

The Scioto was built in 1875 and was considered one of the fastest on the Ohio River with dimensions of 150 feet in length and 22 feet 6 inches in width. By 1882, she was running the Wheeling and Parkersburg trade route carrying goods, freight and passengers between the ports. Captain Thaddeus S. Thomas was owner and master of the vessel on this particular excursion. Among his crew was his son Daniel Thomas, who worked in the engine room, and pilot David Kellar.

THE CELEBRATION BEGINS

The East Liverpool wharf was bustling with carriages and people as the Scioto sat peacefully in the early dawn light puffing clouds of white steam from her engine room scape pipes. On her stern flew the majestic American flag with its 38 stars and 13 stripes on what was America’s Independence Day.

One by one the steamer’s passenger manifest grew to nearly 400. Onboard, young couples jockeyed and hustled to find seats along the railing of the shaded “boiler deck” or above it on the open-air top deck known as the “hurricane deck.”

Inside the main cabin lounge, passengers mingled and chatted as they prepared for what they hoped would be an enjoyable cruise. At 6:30 a.m. and with the last of the passengers embarking at East Liverpool aboard, the steamer backed out into the Ohio and turned south to begin its journey.

Before getting fully underway, the vessel made additional stops in Wellsville and Steubenville adding another 100 excursion seekers, including the Cornet Band. The vessel, normally registered to carry less than 70 passengers, now carried over 500. Festivities for the holiday included picnic socials, music and dancing on board, and a tour of the relatively new Moundsville State Penitentiary grounds that had only been built 16 years prior, as well as the nearby Grave Creek Mound. After several hours of sightseeing and steaming downriver, the boat arrived in Moundsville at about 1:30 p.m.

The day’s itinerary having been fulfilled, it was time to board and head back upriver. Additional passengers were taken on before departure adding to the already overloaded vessel’s manifest of 500 plus passengers.

In the days before more stringent passenger safety laws were in place, steamboat owners and captains rarely turned down a paying customer. This particular excursion was no exception. Captain Thomas, well aware of his vessel being heavily overloaded, determined it best to reduce steam in order to reduce the chance of a boiler explosion as a result of the vessel’s engines being overworked as it plowed upriver. Glancing at his gold pocket watch from within the pilothouse, Capt. Thomas gave the order to depart. At about 4 p.m., the Scioto raised steam and departed Moundsville bound for East Liverpool, which would not be reached until after 10 p.m.

A FATEFUL DECISION

Once underway, the celebration onboard continued. In the main lounge, passengers were entertained by the band with dancing and socializing. Many had imbibed in alcohol throughout the day and continued as the vessel steamed home. Sometime shortly after departure, Capt. Thomas’ watch ended as he took leave to rest in his cabin. Pilot David Kellar, allegedly imbibing throughout the day himself, now took command of the vessel.

At about 9 p.m., the Scioto was south of Mingo Junction on the West Virginia shore when it spotted a downbound vessel rapidly approaching through the dark, cloud-covered night. The John Lomas, with its own complement of passengers, was on the Ohio side of the channel.

Laws at the time dictated that the downbound vessel had the right to first signal with its whistle which side of the river it intended to take in order to safely pass the other. According to Lomas Captain Inglebright’s statement in the July 5 edition of the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, his pilot B.J. Long gave one long blast on the whistle to signal his intention to remain on the Ohio side of the river. Kellar, failing to hear or completely misunderstanding the Lomas’ signal, gave two blasts on his whistle effectively signaling to the Lomas that the Scioto intended to keep the same position. When it was realized that the vessels were on a collision course, he ordered the engines in full reverse, but it was too late. The Scioto’s fate was already sealed.

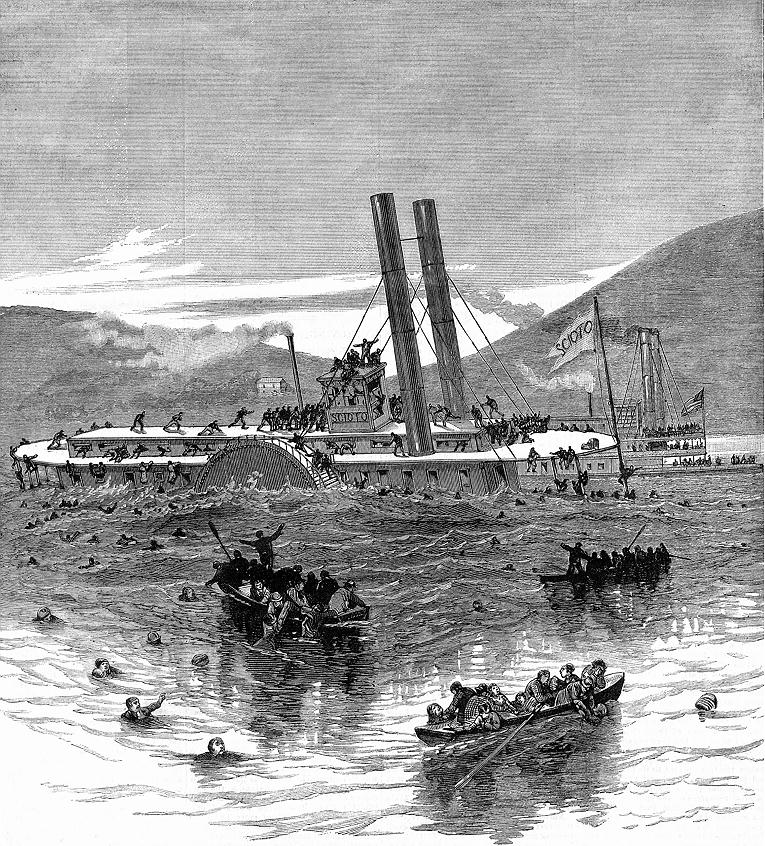

At full steam, the Lomas slammed into the port side of the Scioto’s bow ripping a massive opening in her hull. Immediately, the Scioto began sinking. The Lomas, while damaged but still under steam, quickly reversed engines and pulled away from the mortally wounded vessel.

Charles Page, the 25-year-old assistant engineer of the Scioto, described the events to the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer hours later:

“I was on watch at the time of the accident and when the boats whistled for passing I noticed there was something wrong, but thought nothing of it, and stepped out on the deck for a second, when I saw the Lomas right on us. I rushed back to my engine, obeyed the bell to go back, which was immediately followed by a bell to stop, and then seeing that the boat was fast sinking, the engineer and I threw a skiff into the river, and then I ran after my coat. When I got back the skiff was so full of terror-stricken people that I knew it would sink, so I jumped into the river and struck out for the West Virginia shore.”

Panic immediately ensued on the Scioto as the vessel rapidly sank. Hundreds inside the main cabin lounge quickly rushed to scramble out on the deck and out of windows to escape the fast-rising water. Out of fear or instinct, many faced a quick decision — remain on the steamer or jump for it. Many chose the latter, jumping into the dark and swift current of the river. Within three minutes, the vessel foundered and settled on the bottom of the river. Her pilothouse and smokestacks, along with a few feet of cabin, were all that remained above water.

The Lomas, damaged but still mobile, quickly nosed into the Ohio shore and disembarked her passengers so as to return to the scene of the sinking and begin rescue efforts. In the darkness, hundreds of passengers thrashed about screaming and crying out for help or loved ones while grasping hold of anything in the water that could keep them afloat. Before the days of lifeboats and lifebelts for every passenger on board, it was every person for themselves. Women in their heavy Victorian period day dresses quickly succumbed to the waters lest they were lucky enough to find an object upon which to cling.

Page, further describing what he witnessed, said:

“I, looking around as I swam, saw a sight that fairly took the life out of me. The water was black with struggling humanity and the expression of the faces was the most terrible that you can imagine. Men, women, and children were crying piteously for help, and some of the screams so unnerved me that I could scarcely swim. But the current was very strong, and as I struck out with all my might I soon got out of sight of the crowd in the water, there being but two boys near me who managed to reach the shore in safety with a little help from me. We swam about a mile altogether, and when we reached the shore it was almost impossible for any of us to stand up.”

Witnesses on shore quickly jumped into action, rowing their skiffs as quickly as possible to the scene of the sinking. There, they encountered debris, life preservers and bodies among the living still thrashing and screaming about in the water. Trip by trip, skiffs and the Lomas alike, rescued dozens each time and returned them to the shore.

DISASTER HEARD ROUND THE WORLD

Word of the collision reached Wheeling late that evening sending the city into a frenzy. Arrangements were quickly made to get a special train on the Pittsburgh, Wheeling and Kentucky Railroad that would transport the mob of reporters from the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer and Register as well as those seeking out loved ones up to the site. By midnight, the train was enroute to the scene. Also onboard was the local Western Union operator who came along with equipment to set up a makeshift telegram outpost that could wire news back to Wheeling.

Upon arrival, reporters found hundreds of people on either side of the river who had descended to offer help to the survivors, look for loved ones and see what happened with their own eyes. Many were dead and missing, including Capt. Thad Thomas’ son Daniel. He was inconsolable with grief and overcome with cold after frantically searching the flooding cabin for his son.

By daybreak on July 5, the devastating news was filtering all over the country with accounts of the disaster being conveyed hither and yon, including in New York’s Illustrated Newspaper. Erected on both shores were booths for the sole purpose of selling food and drinks to spectators who came to see what lay before them. Campfires and tents of those relatives seeking loved ones or just the curious onlooker dotted the shorelines. A reporter from the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer described the boat’s condition upon his arrival to the scene of the accident:

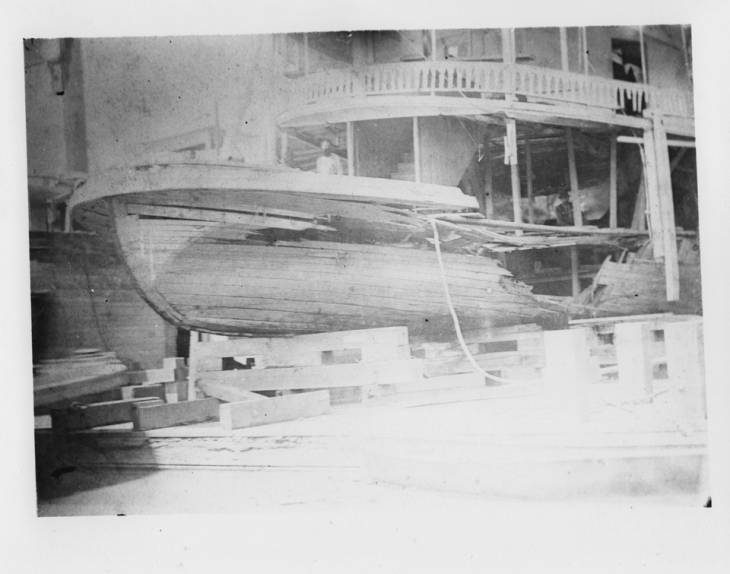

“We first took a view of the sunken boat, which rests in about nine feet of water, the river having fallen about four feet since the disaster. The bow being about 200 feet from the Ohio shore, the boat laying diagonally with the river, which, of course, throws her stern out toward the channel. Entering the cabin, we found about eight inches of water on the floor in the center, but the bow and stern were now clear.”

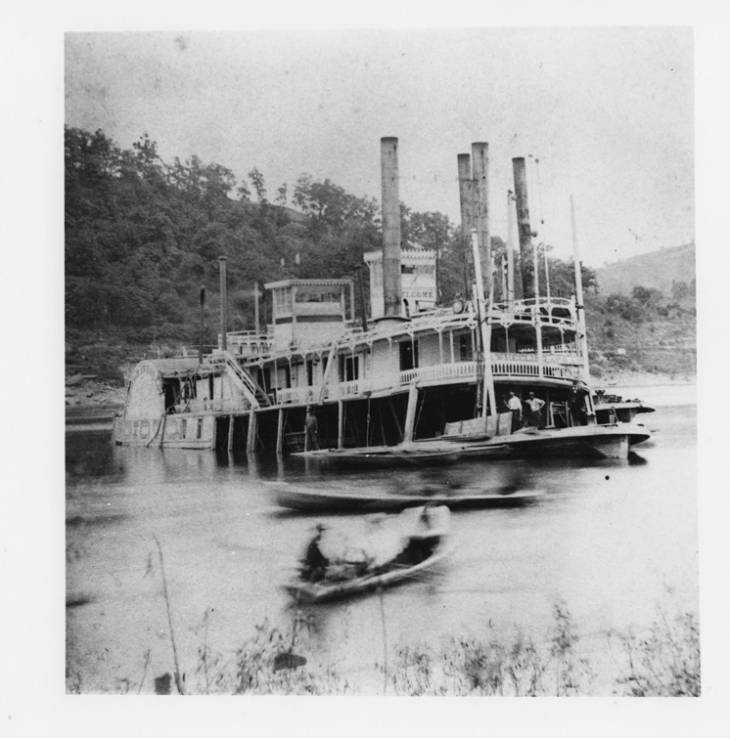

At 5:30 p.m., the steamer Welcome arrived at the wreck site under the command of Capt. C.H. Booth, president of the Wheeling and Parkersburg Transportation Company. Onboard was pilot David Kellar, John Sweeney, a son of Capt. Thomas and others. Crews scrambled aboard the sunken vessel and began transferring all furniture and property from the Scioto as well as any personal possessions of the victims so as to avoid looting or souvenir seeking attempts.

While hundreds survived, the death toll kept climbing. For days following the disaster, the grisly task of recovering bodies, both on the vessel and along the banks of the Ohio, continued as evidenced in the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer:

“When the cabin floor of the steamer was removed a number of hats belonging to men and women were seen floating on the top of the water, which substantiates the theory that a number of bodies had lodged in the deck room. Capt. Chas. Booth is at the scene of the wreck working heroically to recover the bodies. He is ably assisted by John Sweeney and Pilot Dave Kellar. The work of dragging for bodies will be kept up all night.”

According to one account, on Saturday, July 8, the discovery of numerous bodies near the Wheeling Wharf created a mob scene as hundreds gathered to witness the recovery efforts. The first body, that of an unknown young man in his 20s or 30s, was found near Wheeling Island wearing a dark worsted suit and gold signet ring on his left pinky. Following inspection of the body, it was taken to Mendel’s Furniture Factory on Eoff Street in a wagon as crowds followed. Here the great mass of humanity waited as, one by one, 13 pine coffins bearing the bodies of the victims emerged from the factory to be carried up 12th Street accompanied by the massive crowds. When it was all said and done, between 57 and 70 were dead, the exact number never to be known as a result of the boat being so overcrowded.

Around the same time, Capt. Thomas, deeply depressed and near crazed with grief over the event, boarded his steamer Telegram at Wheeling. He forbade any visitors to his stateroom, save those whom he found to be close friends or family. Those who laid eyes on the man hardly recognized his face, which had aged overnight from the ordeal. His eyes were wild as he clasped his hands over his forehead in agony. When he was finally able to speak with John Sweeney he said:

“Oh, my God; my God, John, it was awful. I can see the poor wretches down in the water, and Dan — oh, where is my boy? We were going along so nicely and in two or three hours more would have been all right and the care would have been off my mind. I was in the cabin, boys, seeing that everything was kept straight, when I heard the whistle blowing, I knew something was wrong, and, going out on the guards, I climbed up the jack-post to the hurricane deck and yelled to Dave to back her. He answered that that was what he was doing but it was too late and the crash came.”

Those listening wept openly with him, unable to hold back their own emotions for a riverman so widely admired and for whom much respect was given. The Telegram returned him to his home in Clarington after learning his son’s body was recovered and among the dead. Days later upon his return trip to Wheeling on the steamer, he refused to allow the boat to land at the levee after learning several of the crew desired to have their whisky flasks filled there. With the ever-present thought of his pilot David Kellar suspected of being under the influence of alcohol at the time of the collision on his mind, he instead launched a yawl and rowed himself to shore in order to prevent the boat from landing and his crew from obtaining alcohol.

THE FINAL SAGA

Following an investigation by the government, it was determined that the Scioto and its pilot David Kellar were at fault. A jury found him guilty of intoxication and manslaughter in 1884 and sentenced him to prison for his role. The disaster would change United States maritime laws forever, including how vessels signal one another and regular inspection of vessels that carry passengers.

The loss of the White Star Liner Titanic 30 years later in 1912 would eclipse the Scioto disaster, relegating it to a quiet corner of the nation’s memory. But, for many who lost loved ones on the Scioto, the Fourth of July disaster would forever change their lives. To date it remains the single largest loss of life on the Ohio River.

The July 10 edition of the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer closed out its story of the day by rightly saying, “In all things it is one of the saddest tragedies that ever occurred on western waters, which will take years of time to efface from the memory of those who witnessed the wreck or were in any way connected with the accident that so cruelly and so swiftly brought death and mourning into so many households.”

• Taylor Abbott is the treasurer of Monroe County, Ohio, and was born in Wheeling, West Virginia. He is a graduate of Ohio University and is co-founder and president of the Ohio Valley River Museum. He serves on the board directors for the Sons & Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen and is an advisor to the Ohio River Museum in Marietta, Ohio. He enjoys hiking, travel, historic preservation and restoration work. Taylor resides in Clarington, Ohio, with his wife Alexandra in a former church they purchased in 2016 and renovated into their home.