Editor’s note: Throughout Wheeling’s history, one aspect has remained a constant — the Ohio River. From the birthplace of the first western-style steamboat to laying claim to the Ohio River’s first suspension bridge to being a major shipping port of Wheeling-made goods to welcoming world-class river cruises — its claim to river fame are far too numerous to count. This occasional series will explore some of Wheeling’s most fascinating and unusual river history and the impact the river continues to have on the Friendly City.

Moving is a pain. Whether an apartment you have lived in a few short years or a home you have spent most of your life in, there is nothing easy about it. You toil for hours packing away everything you can cram into boxes, doing your best to do so in an organized manner. You debate and argue with yourself, oftentimes out loud, about whether you really need that item you hold in hand until finally you make a judicious decision.

At last you finish packing the last box and breathe a sigh of relief. … Then reality sets in — you get to do it all again at your new place, this time in reverse.

If the thought of that isn’t tiring enough for you, imagine actually moving it back and forth from the same two places repeatedly.

That’s exactly what the newly formed state of West Virginia did with its capital between 1863 and 1885 via the Ohio and Kanawha rivers. But before anything could be moved by river, many events took place leading up to it on land.

A HOUSE DIVIDED

The outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861 was quickly followed by the secession of Virginia from the Union on April 17. The Virginia Secession Convention succeeded in garnering enough votes to break away, but not without 30 of the northwestern Virginia’s delegates voting against it.

Delegates from that part of the state converged on Wheeling on May 13, 1861, for the First Wheeling Convention. Gathered inside Washington Hall, 425 delegates from 25 western Virginia counties prepared to debate the formation of a new state. (Note: Washington Hall, built in 1851 and destroyed by fire in 1876, was located at the site of the present-day Laconia Building.)

According to Richard O. Curry’s “A House Divided,” the convention opened with division already sewn throughout the delegation. Delegate John S. Carlisle, backed by supporters in his corner, voiced his belief that a new state should be formed at once. However, his counterparts argued that Virginia’s secession was not legal until the voters of the state approved the referendum. Seeing the rationale of the latter’s argument, the delegation agreed to hold a second convention in Wheeling pending the outcome of Virginia’s vote on the referendum. That day came on May 23 when a majority of the state’s voters formally approved secession.

On June 11, the Second Wheeling Convention was called to order to finish what it had started a month prior. The first order of business for the delegation gathered inside Washington Hall, according to historian Chisholm Hugh, was to declare Virginia’s Secession Convention illegal due to it being called without popular consent. Thus, they determined, its actions were entirely void, and all elected officials who voted in favor of secession effectively vacated their offices.

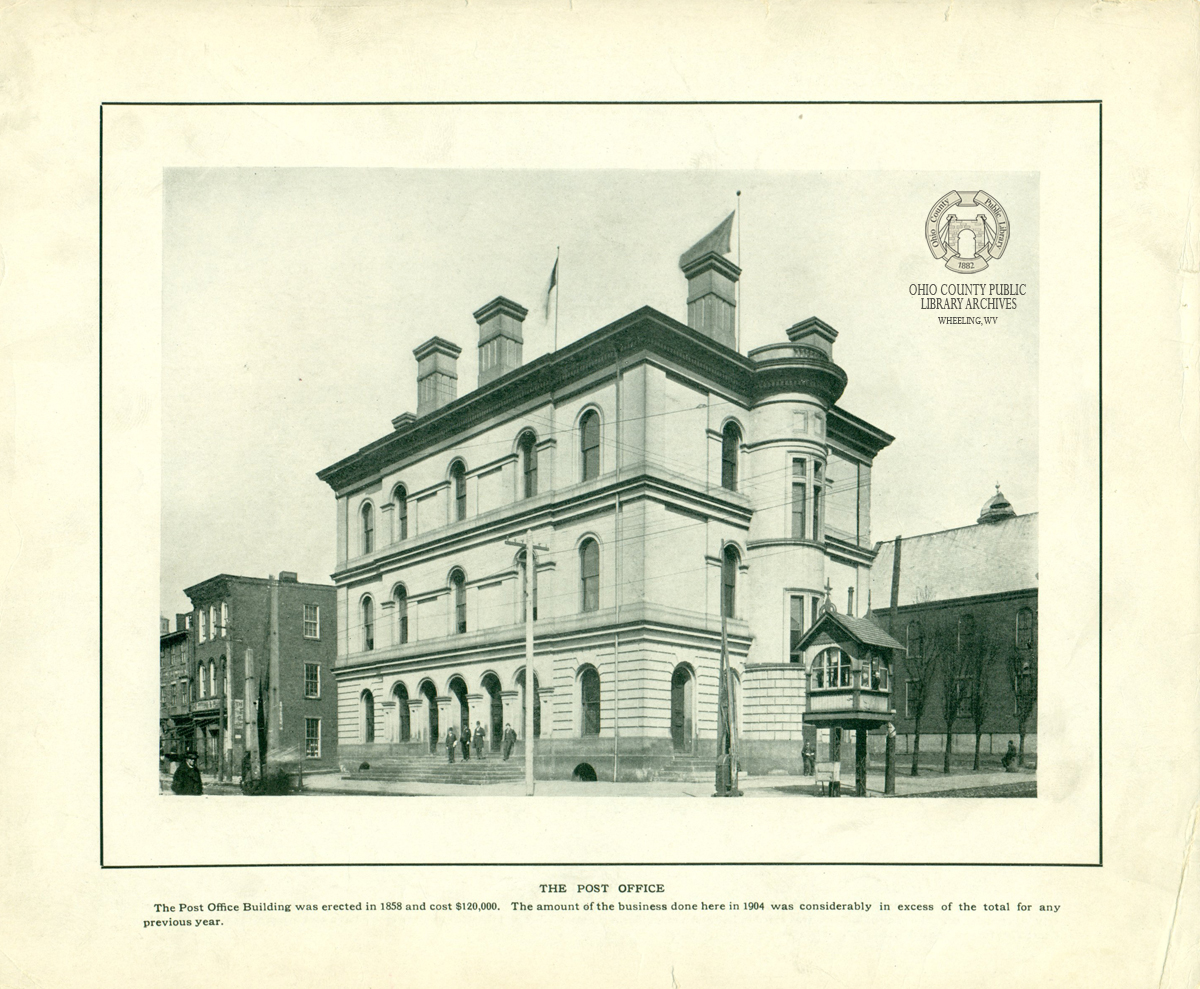

After the first session was completed, the convention moved to the Custom House. Unlike many other federal buildings seized across Virginia by the state following secession, Wheeling’s Custom House was not.

Eight sweltering days later, on June 19, the convention delegates formally passed an act for the reorganization of the government. The following day, delegates elected Francis H. Pierpont as governor of the new state government of Virginia — a government that would take the place of the seceded one then occupying Richmond. Two new senators were also chosen and seated in the U.S. Congress. In August, delegates reassembled and decided a popular vote for the formation of the state would be held. On Oct. 24, 2,861 voters approved the creation of the new state.

WELCOME TO THE UNION

Following the state legislature’s approval and the application of admission to the Union being made to Congress, President Abraham Lincoln approved the enabling act permitting the new state of West Virginia to join the Union on Dec. 31, 1862. According to Hugh, he did so on the condition that the abolition of slavery be included as a provision in the new state’s constitution. Having sufficiently met those requirements, Lincoln’s proclamation admitting the state became effective June 20, 1863, thus welcoming West Virginia to the Union.

With statehood now official, the business of the newly formed state could proceed. But what was a new state without a capital city? For its part in being the birthplace of West Virginia, it was only fitting that it, too, should then be the capital.

Gov. Arthur I. Boreman delivered his inaugural address from a special stage assembled outside the Linsly Institute building before a large crowd on Eoff and Fifteenth streets. The June 22, 1863, issue of the Daily Intelligencer captured the events of the day:

“As anticipated, Saturday was a great gala day in the city. There were thousands of people here from abroad and the city turned out its entire population… Flags of all sizes, were as thick in the city almost as the locusts in the suburbs. The display of bunting was most attractive and reflected much credit upon the good taste and patriotism of the people… In the evening thousands of people were attracted to the wharf where a fine display of fire-works had been arranged. The pyrotechnics were grand, varied and beautiful and elicited universal murmurs of admiration.”

For all its celebrations, the question of Wheeling remaining the capital was quick to find its way into many speeches and conversations. The first of those to do so publicly was Gov. Boreman, who sought to end the debate and settle on a permanent location immediately. However, the legislature failed to act upon Boreman’s recommendation. Instead, the body adopted a joint resolution authorizing Boreman to designate the Linsly Institute building as the capitol building but made no mention of a permanent capital. The building would continue to serve in this capacity until, finally in 1869, momentum to select a permanent capital grew.

In February of 1869, the House passed a bill locating the seat of government to the town of Charleston in the county of Kanawha. The act became effective April 1, 1870.

ON THE MOVE

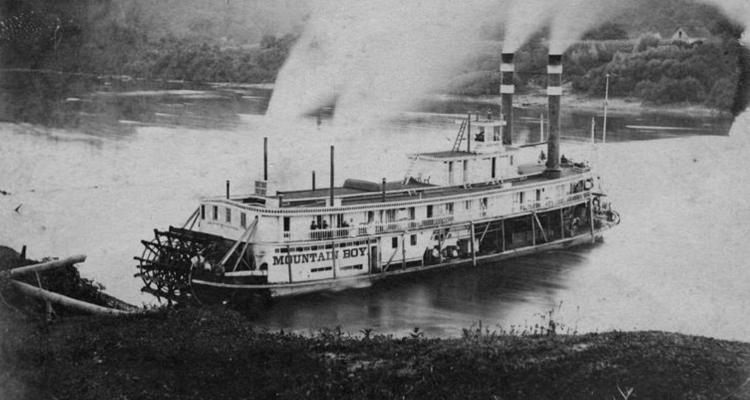

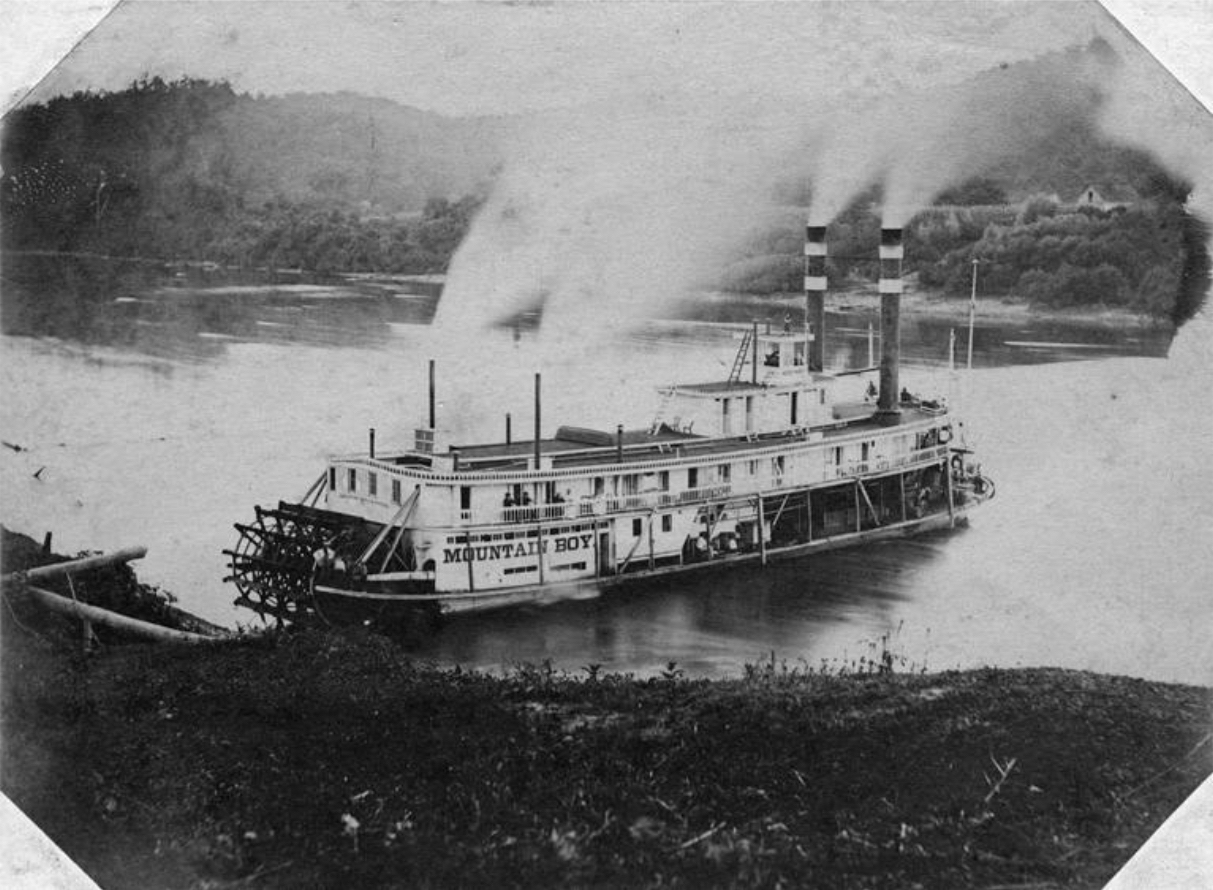

According to the “West Virginia Blue Book of 1922,” a jubilant Charleston wasted no time in preparing to move the capital out of the Friendly City. Citizens charted the steamer Mountain Boy to bring the state’s treasure trove of archives, furniture and other articles as well as the state’s top executives to their city. On March 28, 1870, the Mountain Boy arrived in the early morning hours with a reception party of state officials aboard. The day was spent loading steamer trunks and boxes filled with books, records, official papers, the state library, as well as the personal affects and furniture of state officials from the Linsly Institute to the vessel. At around midnight that evening, the packet boat raised steam and, bedecked in flags and bunting, headed downriver with the entire contents of the state’s government stored safely within. Two days later on March 30, 1870, the steamer arrived in Charleston.

However, Charleston’s jubilation was to be short lived. Only just five years into its role as the new capital, complaints from the northern parts of the state and those areas where travel to Charleston was not easy were soon apparent. Without railroad access, the city was only to be accessed by boat during good weather or by stagecoach.

Agitation among many grew until it could be contained no further. By 1875, the issue was on full display when delegate John M. Bennet of Lewis County introduced Senate Bill 29 titled, “A Bill to remove the seat of government temporarily to Wheeling.” The bill passed the legislature and became law on Feb. 20, 1875, without then-Gov. John J. Jacob’s signature.

Like Charleston, Wheeling wasted no time in making preparations to receive the capital and all its trimmings. Citizens in the city set out at once to procure a building worthy of being called a capitol by forming a Capitol Committee led by Capt. John McClure. Without question, the intention was to build a structure so grand in scale that moving yet again would be unthinkable. The city issued $100,000 in bonds to erect the new building which were purchased in their entirety by three banks and one private individual.

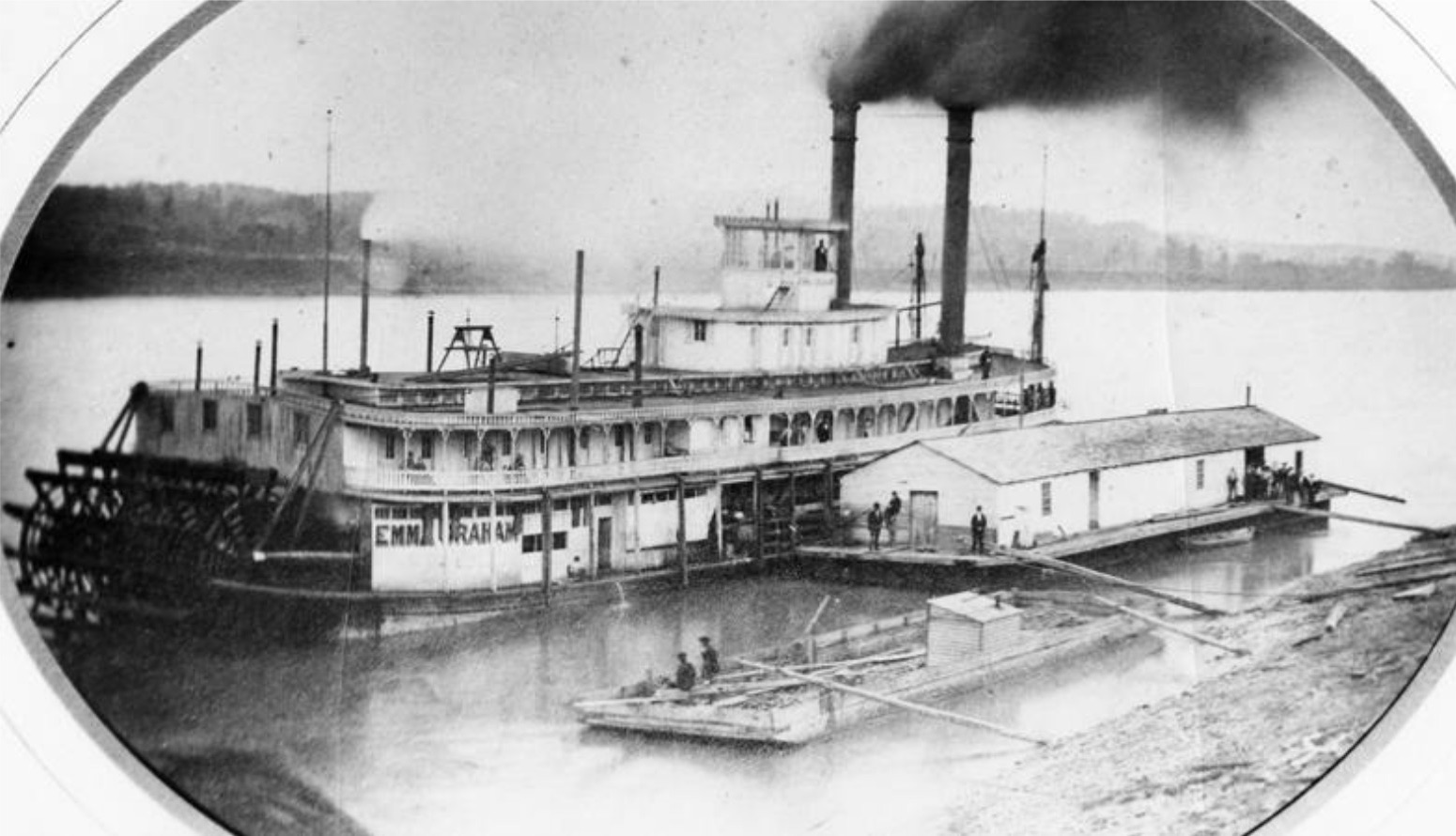

With full particulars in order, Gov. Jacob issued a memo to all state offices ordering their records and any other items deemed “official” to be crated and readied for transport. Wheeling defrayed those expenses by appropriating $1,500 ($35,000 in 2020 terms) and by chartering the steamboat Emma Graham to return the records and state papers. On May 21, 1875, the Wheeling Removal Committee led by Capt. McClure arrived in Charleston. However, a court injunction and various other hiccups contesting the removal from Charleston to Wheeling, including writs being served to the assembled officials, resulted in the party boarding the vessel and leaving empty handed pending a Supreme Court of Appeals ruling that would settle the dispute, according to the “West Virginia Blue Book of 1922.”

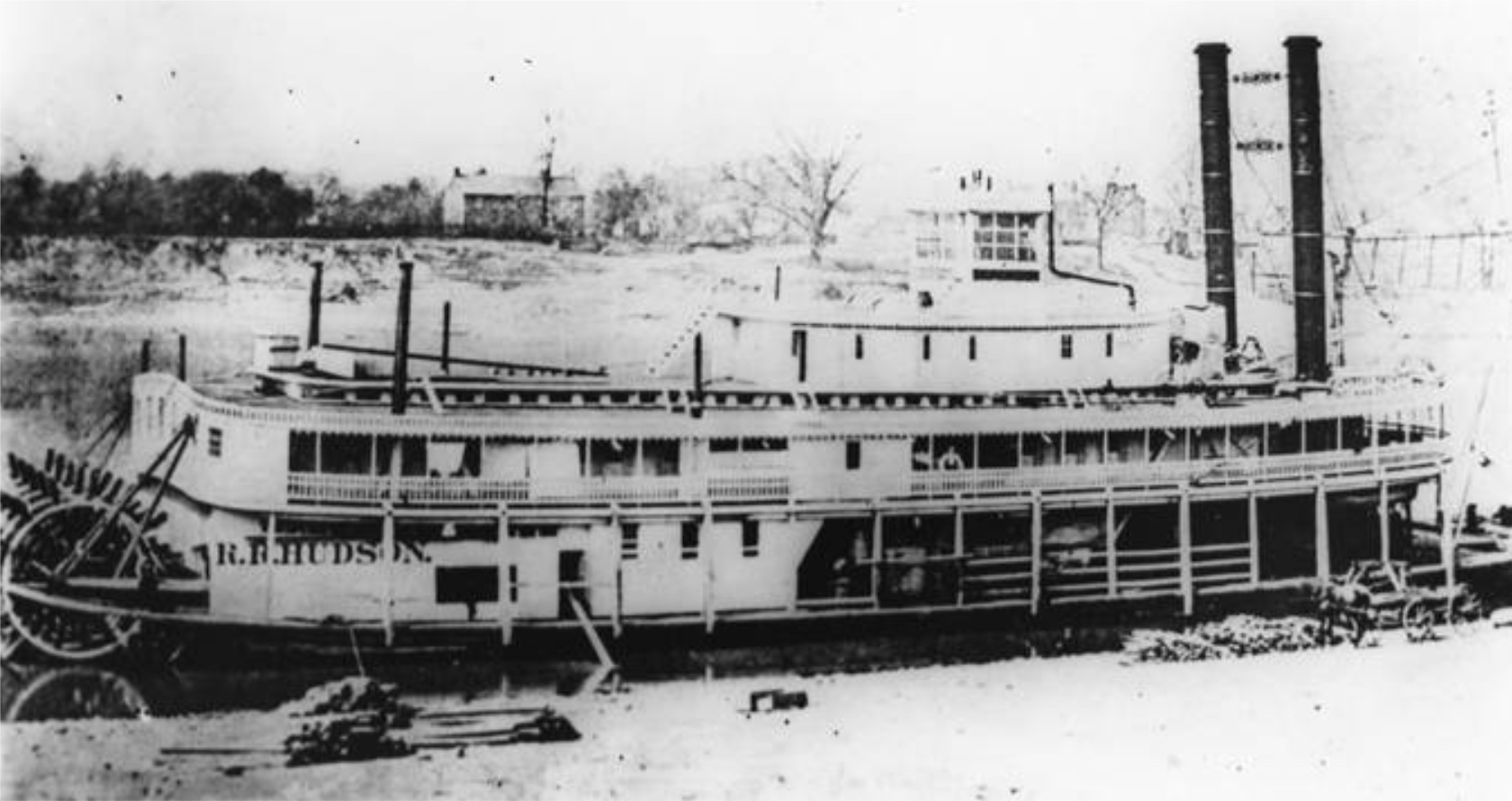

Later that evening, the steamer arrived in Parkersburg where the delegation of officials was transferred to the sidewheel steamer Chesapeake. As the vessel steamed upriver, it was met near Sistersville by the steamer RR Hudson, who had onboard a welcome party of Wheeling citizens dispatched with great excitement to escort the Chesapeake back to Wheeling. However, the officials and parties involved arrived in Wheeling that evening to barren shelves and offices inside the former capitol, the Linsly Institute building.

MOVING FORWARD, MOVING NORTH

The Supreme Court of Appeals rendered a decision to dissolve the existing injunction effectively paving the way for Wheeling to move forward with retrieving the state property left behind on the first attempt. The steamer Iron Valley was contracted to tow two barges that would carry the items to Wheeling, leaving Charleston on Sept.22, 1875 and arriving three days later.

The court ruling and arrival of state property effectively cleared the way for the Capitol Committee to move forward on a new capitol building located at 16th and Chapline streets. Architect J.S. Fairfax was tapped to design the new building at a cost of $82,940 ($1.9 million in 2020). The imposing structure became operational on Dec. 4, 1876.

Conventional wisdom would suggest that moving a capital for the second time to its original location into a new capitol building specifically built for the purpose of permanently housing the government would certainly be its last, right?

Wrong. Hardly had the smell of fresh paint worn off before the legislature once again heard rumblings throughout the state regarding the lack of a permanent capital and talk of moving it for a third time was openly discussed. By 1877, the legislature was ready once and for all to put an end to an issue that had thus far plagued the state now only in its 13th year.

This time however, the legislature was prepared to put the question to the voters. Bill No. 25 provided for a permanent selection of a capital city, the erection of a proper capitol building, and a vote by the people in selecting its location. Choices for the permanent capital were Charleston, Martinsburg and Clarksburg. Wheeling was notably snubbed because of its location so far from the southern portions of the state and, allegedly, the “stuffiness” of the city compared to the rest of the state. On the first Tuesday in August 1877, voters declared Charleston the winner.

WELCOME BACK TO CHARLESTON

Once again, the removal of state property and official records were crated and made ready for the all-too-familiar journey back to Charleston. The steamers Chesapeake and Belle Prince pushing were summoned to convey the property. On the morning of May 2, 1885, the vessels raised steam and departed for the nearly 220-mile trip to Charleston carrying with them the entire state of West Virginia’s government. Upon their arrival, steamers of all varying size and degree exchanged whistle salutes welcoming back the dignitaries and state property aboard the two steamers. On the deck of the Belle Prince, a crew member fired a canon salute, much to delight of spectators lining the shore, heralding the arrival and return of the government to Charleston once and for all.

Wheeling’s beautiful second capitol building would become the City-County Building before being razed to make way for the current Ohio County Courthouse. Still standing to carry on the legacy begun in the city is Independence Hall and the Linsly Institute Building, which you can visit today.

• Taylor Abbott is the treasurer of Monroe County, Ohio, and was born in Wheeling, West Virginia. He is a graduate of Ohio University and is co-founder and president of the Ohio Valley River Museum. He serves on the board directors for the Sons & Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen and is an advisor to the Ohio River Museum in Marietta, Ohio. He enjoys hiking, travel, historic preservation and restoration work. Taylor resides in Clarington, Ohio, with his wife Alexandra in a former church they purchased in 2016 and renovated into their home.