Whatever voters decide come Nov. 6 on $22 million of potential new and upgraded digs for city fire and police departments, one thing is indisputable. Facilities to be potentially replaced — launched in the 1950s and ’70s — were in no way designed for seized street drugs strong enough to drop an elephant, computer networks aimed at nabbing pedophiles or the occasional firefighter who wears a bra.

“They issued shorts for everyone to sleep in,” says Captain David Harmon, ranking officer at the city’s fire headquarters. That 1978 facility is wedged under a parking garage that serves the Centre Market area and Ohio Valley Medical Center. Perhaps embarrassed to be discussing co-workers’ sleepwear, Harmon motions only vaguely to a bunk room where the occasional female firefighter and her male co-workers sleep en masse.

Male and female spaces are causing similar issues at police headquarters in the City-County Building — where male officers share a restroom with female detainees, while female officers and staff (more than 10 percent of the department) have to plan restroom breaks for when there is time to trek deep into the interior of the office complex. But it is perhaps felt most keenly at the fire department.

“This is where I live 10 days out of the month,” Harmon said.

He is not alone. Firefighters, who make up the lion’s share of the 94 department employees, work on 24-hour shifts that include a sleeping period. And time spent getting in and out of gear and washing up. “The guys file out,” he said of making space in a bathroom and locker room for the department’s current lone female firefighter. (Until recently, there were two.)

Space Issues: Fire

Tricky gender issues aside, both departments say their hope for a combined, dedicated facility is about not only the right kinds of space for everybody and everything, but enough space.

Here is a look at those space issues, beginning with fire headquarters:

One of two fire buildings to be potentially replaced with a new safety building — the other being a smaller 1970s station in North Wheeling — the current headquarters is integrated into a parking garage. Harmon said that has led to an ironic problem — too much water. When it rains, or if cars parked overhead are covered with melting snow, the station leaks.

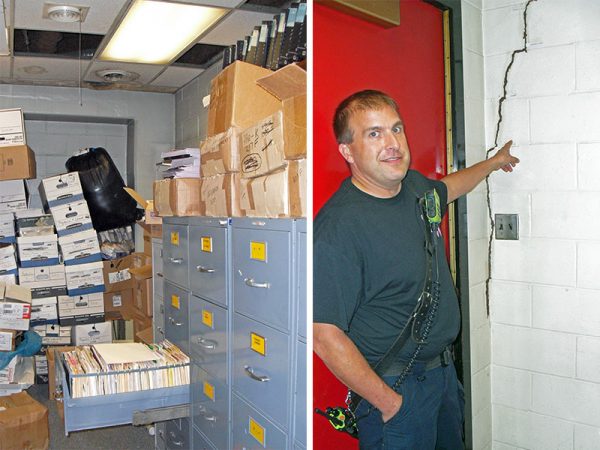

Everywhere. Throughout the building, many ceiling tiles have been removed and still more are water stained. Firefighters walking through the engine room duck strategically to avoid a persistent drip that hits just behind one truck. In one hallway, a large crack zigzags down the cinderblock wall. A staff wag has penciled in a rough labeling system, suggesting it is a river map.

Harmon noted nearly all of the department’s neighborhood stations — which are included in a repair and equipment upgrade package nested in the proposed bond issue/levy — have roofing issues. Levy or not, he said money is going to have to be found to keep the current structures functional.

There’s also the whole in-and-out issue, he added. At headquarters, drivers backing engines 30 feet or more in length into a bay block off the entire street in the process. Often, a second firefighter stands in the street to direct traffic.

Situated in busy Center Wheeling, the headquarters bays face a florist, where pots of mums are on street display just feet away. In North Wheeling, where Harmon said driving space is even tighter, ambulances have been hit several times while returning to the station. No injuries, but costly damage.

Also factoring in space issues, duties have changed over the decades, Harmon said. Today’s hybrid department responds to vehicular accidents and medical emergencies in addition to firefighting — and requires equipment past generations of firefighters simply didn’t need.

There are stretchers, inflatable boats for swift-water rescues, a pile of resuscitation dummies for public and business CPR training.

“We have a trailer parked in the bus garage,” Harmon said, ticking off on his fingers the locations of various pieces of yet more equipment stored by the department itself and on behalf of a regional mass-emergency team launched after 9/11. “We’re very cramped for space.”

Indeed, when the captain shows crowded conditions in a records room, a box falls over as he tries to close the door. More boxes are delivered during this interview, left by UPS at the bottom of a steep stairway, the only staff or public access to offices and a training room on the station’s second floor.

“It’s not just to meet our needs today, but our needs in the future,” Harmon said of the levy issue. “The chances of us doing less is going to be slim. If anything, we’re going to be doing more.”

An ironic final issue is safety space. Right now, if firefighters return to headquarters with blood or feces on their boots (which Harmon says is not uncommon), they disinfect on a doormat-sized device just inside the station’s foot entrance and right next to an engine. He’d like to have those kinds of contaminants — and fire gear coated with fumes from burning plastic — much farther away from areas where staff eat and sleep.

Space Problems: Police

Space issues are similar at police headquarters, a 1959 space in one corner of the City-County Building. At just over 4,600 square feet, every inch is kept in play by nearly 90 employees, according to Philip Stahl, a civilian employee who serves as public information officer.

Stahl said safety is also a space issue for police, noting Chief of Police Shawn Schwertfeger is particularly concerned about entrances and exits, booking areas and proper facilities for everything from ammunition storage to drug testing.

On the latter, substances that can include the potentially deadly narcotic fentanyl are tested on a small lab cart in a similarly small multi-use room. Elsewhere in the room, detainees suspected of DUI have their breath analyzed, boxes of cameras purchased with a recent grant are waiting to be stored somewhere, and one end of a table is available for meetings.

A sign on a cabinet reminds officers: “Do not test drugs on the table.”

Stahl shrugs in frustration when asked about the sign and heads to another room, where visiting workers have an array of computer cables dangling from the ceiling. A tight group of desks shared over multiple shifts — each detective has a dedicated drawer, he explains — are covered with papers and boxes displaced by the re-wiring.

“Every time we add a computer and a body, we need space for that,” said Stahl. He noted certain crimes, such as online pedophilia and credit-card fraud did not exist when the station was designed.

Nor did elements of modern forensics. In an evidence processing room small enough that Stahl can touch both side walls at once, a climate-controlled tank holds blood-stained shirts in storage for a murder investigation. To see into the tank, one has to step over a box of tools.

Even after processing, (which sometimes includes a trip to state labs), storing evidence also has become a space issue. A locked room where everything from seized drugs to shotguns is jam-packed and will likely stay that way, he said. The possibility of appeals means evidence sticks around long after a guilty verdict.

Elsewhere in the station, one officer is working in a literal closet. Street patrolmen and women share four terminals for filing reports, acknowledging that if all four are busy, they return to their squad cars and patrol until a computer is free. There is no place to wait in line.

In a front reception area, spackle marks one wall, and there are holes in the carpet. “This is a 24/7 office,” Stahl noted of the wear and tear. “This place has never been shut down. It’s been open for 60 years.”

What’s Actually on the Ballot?

Voters will decide whether to fund the proposed safety building and upgrades to neighborhood fire stations during the Nov. 6 general election.

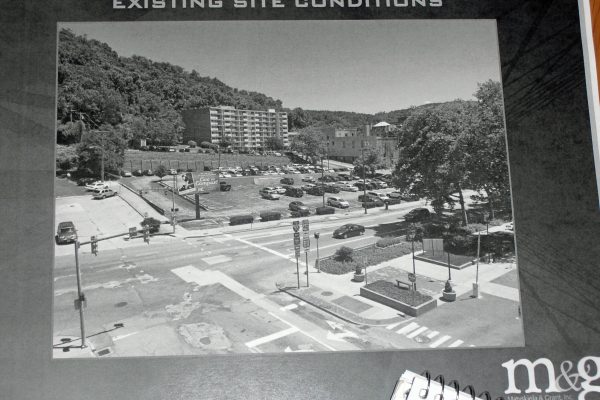

If the 60 percent majority of votes is there, the city will sell $22 million in bonds to construct a new facility on city-owned land at 10th and Market streets, just south of the I-70 bridge access. The new facility would replace both downtown fire and police headquarters and a small fire station in North Wheeling.

City plans indicate the safety building would provide the police with nearly 19,000 square feet of space, with the fire department getting nearly 25,000 square feet. An additional 13,000 square feet of space would be shared.

Repairs and upgrades to the remaining neighborhood fire stations are also included in the bond package, as is a new fire truck for the Warwood station.

It would take taxpayers about 15 years to pay off the bonds, according to the city proposal. For a homeowner whose home has a market value of $110,000 (the city’s average), that would mean a $105 annual increase in taxes over that time period. Market value is different than assessed valuation, the dollar figure the county assessor attaches to properties. Assessed value is about 60 percent of market value.

And the spaces that would be replaced? Harmon said there is talk of the existing fire headquarters being converted into additional parking in the parking garage that surrounds it, if the safety building materializes. The parking garage is already set for an upgrade connected to the recent change in ownership at OVMC. Retail space also has been discussed. The North Wheeling station could be sold, he said. The county commission, Stahl said, already owns the City-County Building where the current police station is located and would be responsible for any future re-use.

Want More Information?

Voters can see the existing headquarters buildings for themselves. Both fire and police headquarters are wrapping up a series of public tours connected to the levy effort. To pre-register (which is a requirement), visit wheelingwv.gov/policetours or call 304-234-3732 for a tour of the police station or visit wheelingwv.gov/firetours or call 304-234-3732 for a tour of the fire station.

City officials will also answer questions about the Public Safety Building Levy in a town hall meeting set for 6:30 p.m. Oct. 29 at West Virginia Northern Community College at 1704 Market St. in the downtown.

Artist renderings of the proposed safety building and answers to public questions can be accessed online at keepwheelingsafe.com.

• Nora Edinger writes from Wheeling, W.Va., where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household. A long-time journalist, she now writes in a variety of print and e-venues, including her JOY Journal blog at noraedinger.com. Her first work of fiction, a Christian beach read called “Dune Girl,” is available on Amazon Kindle.