When that boy grows enough ass to break his neck, they ought to hang the bastard.”

Those words, once spoken about the late Col. Charles Askins in his youth, might have been better saved for Sam Mason, had they known how he would finish his career. Askins lived long enough to best his critics. He became world renowned as a national pistol champion, lawman, writer, and big-game hunter. Sam Mason’s career on the frontier trended toward just the opposite direction. After a quite promising start, he became an outlaw in spades, and met with a suitably evil end.

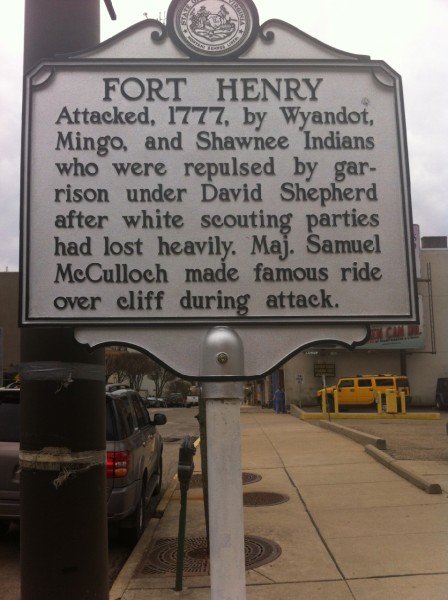

Sam Mason was certainly something of a paradox. There was nothing in his early days in Wheeling to indicate he would be one of the most feared and bloodthirsty brown water pirates of the lower Ohio and Mississippi rivers. To the contrary, if we were to examine just the time he spent in Wheeling, most would wonder if we were studying the same person. The titles associated with his name during the Wheeling period of his life were scout, militia captain, magistrate, road builder, tavern keeper, and hero of the first siege of Fort Henry. The Draper Manuscripts mention him as originally hailing from Virginia. He most likely came to Wheeling in the first large wave of newcomers in 1774.

The first official mention of him in the area was from the famous “Council of War” held in Washington, Pa., in January of 1777. This meeting was held to see to the defense of the area. To aid in that task, a request was sent to the state government of Virginia for 1000 rifles and ammunition. Nine militia companies were organized, and Mason was picked to be the captain of one of them. He must have been something of a natural leader, for it should be remembered that in those days militiamen elected their own officers. A few months later, when the government of the newly formed Ohio County was organized, he was picked to help build the first county road which was to run six miles from Fort Henry to Shepherd’s Fort (Monument Place in Elm Grove).

During the spring and summer of 1777 the Indian raids burst upon the settlers of the Ohio Valley in full fury. Letters written in Mason’s own hand show that he and his company were busy nearly the entire summer scouting the area and giving chase to the raiders. Conditions in the newly formed Ohio County deteriorated to the point that Col. David Shepherd suspended the civil government and declared martial law. That August Col. Shepherd had received word from Gen. Hand at Fort Pitt that a large-scale attack on the area was imminent. All nine militia companies were mustered and stationed at Fort Henry. When the raid failed to materialize, seven of those companies were dismissed. The only two that stayed on were Mason’s company, which was to garrison the fort, and Ogle’s company, which was sent on a scouting expedition up the river and had returned on the evening of August 31.

Around 6 am on the morning of Sept. 1, 1777, the first siege of Fort Henry began. A slave and a bondservant had been ambushed by a few Indians at the crest of Wheeling Hill (near the day site of the McColloch’s Leap monument). A second and larger party from the fort was also ambushed in that same area about an hour later. Though a thick morning river fog lay over the area, from the south wall of Fort Henry, someone spotted activity in a cornfield down near the mouth of the creek. To those in the fort, these Indians were undoubtedly the ones who had just sprung the double ambush at the top of Wheeling Hill. Col. David Shepherd ordered Mason and 14 of his men to go out of the fort and kill or disburse them. The group fanned out and formed a skirmish line and proceeded slowly to the south. A thick morning mist hung over the area like a funeral pall and must have seemed like an ill omen.

As Mason and his men approached the mouth of the creek, the Indians moved off to the east. Mason’s company wheeled left and followed them for about another 300 yards when he and his sergeant saw two warriors materialize out of the fog. All four men fired almost simultaneously, and Mason was the only one left standing. Now seriously wounded, Mason found himself in the middle of nearly 200 howling Indians who had been waiting in ambush. In the course of the panic-stricken rout and massacre that followed, Mason killed another Indian and was wounded a second time. Unable to get to the fort, he spent the rest of the day in hiding. After the siege, Mason was hailed a hero for his part in the fort’s defense. Significantly, the Indians suffered only three fatalities in that fight, and Sam Mason was responsible for two of them.

Mason continued to serve the Patriot cause in the western theater of the American Revolution. He was a member of George Rogers Clark’s expedition in 1778 and also served in Brodhead’s campaign against the Indians living on the upper Allegheny River in 1779.

For the next few years Mason kept a tavern in the Fulton area of Wheeling. Based on certain documentary and physical evidence, it is this author’s belief that his tavern was located approximately 200 yards west of the present-day Generations Pub, in a ravine near the base of Wheeling Hill. He was later listed in Boyd Crumrine’s excellent History of Washington County as a magistrate in Washington County, Pa., in 1781.

There is no mention from any source of Sam Mason’s being at the second siege of Fort Henry in 1782. It is about this time that dark rumors became associated with his name. A contemporary, George Edgington, would later write that Mason, “…settled on Wheeling Creek with a bad name from the start – [a] horse thief. He had two sons, one John and two sons-in-law, all of a feather.”

By the mid-1780s Mason had left the Wheeling area for good. During the next few years Mason and his sons-in-law became land swindlers, working around the Marietta, Ohio, area and to the south. They would sell phony land titles to newly arrived settlers. His travels took him to Evansville, Ind., and eventually to the infamous Cave-in Rock in Illinois.

Cave-in-Rock is located in Hardin County, Ill., on the North bank of the Ohio River. It was at Cave-in-Rock that Mason’s criminal career began to hit its stride. His next criminal enterprise was that of a counterfeiter or “coiner” as they were known in those days. As his greed grew, he was no longer content with crimes of theft by deception. Mason took up his old trade as innkeeper, but with a decidedly deadlier twist. He outfitted the cave with a liquor supply, and converted it into a tavern. A sign hung outside the establishment billing it as “Wilson’s Liquor Vault and House of Entertainment.” The “entertainment” was supplied by his daughter-in-law, some female slaves, and female consorts of his outlaw band. Perhaps better than Mason would have hoped, the combination of riverside bar and bordello proved irresistible to the rambunctious and lusty riverboat men. For the river men who stopped to sample Mason’s hospitality, it was a one-way ride. Those who went in never came out alive. It was standard practice for the freebooters to murder the entire crew and commandeer the boat and cargo. The boats were then crewed with Mason’s henchmen, floated down the river to New Orleans, and the purloined property was disposed of.

As a surprise to no one except Sam Mason, not all of his confederates and the gold made it back to the Cave-in-Rock hideout. Certainly giving credence to the old maxim “there is no honor among thieves,” some of his outlaw crews disappeared without a trace. Most probably they took their ill-gotten gains and had a wild spree in Natchez or New Orleans. Each of those cities featured a section occupied by prostitutes, card sharpers, swindlers, and the inevitable enforcers that are spawned by those dark trades devoted to sin. The New Orleans section was known as “the swamp.” Its counterpart in Natchez was known as “Natchez under the hill.” Both of these sections had several pleasure palaces that catered to the high rollers and offered every vintage that one might desire from the vineyards of vice. These were places that honest people did not venture more than once. Even the outlaws that haunted these locations usually made short and violent work of each other.

For the local banditry on the lower Ohio, Mason’s tavern offered a sort of one-stop shopping vice emporium. Though not quite so elaborate as the down-river establishments, at the Cave-in-Rock they could still soak up as much of the demon rum as they wished, gamble, dally with the girls, and fence their stolen property. They might even trade their stolen goods for counterfeit coins or paper money, to further enhance their profit margins.

For all the violence and bloodshed that occurred at Cave-in-Rock, it is rather ironic that Mason became acquainted with a pair of killers that offended even his sensibilities. Two brothers by the last name of Harpe joined Mason’s gang in 1799. The older of the two was named Micajah, better know as Big Harpe, and the younger sibling was named Wiley, usually known as Little Harpe. This lethal tandem may have been two of the most dangerous psychotic killers ever to set foot on American soil. Robbery was an occasional motive for them, but usually they just killed for the sheer ghoulish pleasure of it. They were equal-opportunity killers as well, killing men and women, black and white, young and old. They are credited with 39 victims that can be directly attributed to them, but the true number is unknown and undoubtedly much higher.

The incident that led to the parting of the ways between the outlaws began after a boat robbery. The Harpes singled out a man for torture. He was taken away from the other river robbers to a high bluff overlooking the cave. There the unfortunate was bound naked, to a horse. The horse was blindfolded and then driven over the cliff to the rocks below where the other outlaws were gathered. The Harpes came down from the bluff to rejoin the group, roaring with laughter, thinking this great fun and quite the practical joke. They were greeted by Mason and his gang, hard-eyed and unsmiling, with rifles in hand. The Harpes were told in no uncertain terms that they had worn out their welcome and must decamp immediately! The incredibly bloodthirsty brothers had managed to offend the sensibilities of a gang of murder-hardened river pirates!

Despite what might seem like many obvious similarities, it was probably inevitable that Mason and his murderous lieutenants should clash. Just as with animals in the wild, in any such human wolf pack there is bound to be tension between the leader and members of the pack wanting to challenge his supremacy. Helping to add to the tension was the fact that during the war Mason had been a Patriot, and the Harpes were Tories. Feelings on that subject still ran high on the frontier. Even their motives were different; Mason killed for profit, whereas the Harpes were basically thrill killers. Hereafter whenever they would meet, it would be as enemies. Approximately six months later Big Harpe met a fitting end at the hands of a posse in Kentucky. Little Harpe escaped the trap and vanished, but he would make a most timely reappearance.

It was sometime during this period that Sam Mason had a chance meeting with another local legend, Lewis Wetzel. In addition to robbing southbound flatboats, Mason also robbed the northbound land traffic along the Natchez Trace. They were of particular interest to Mason, as many of them had sold cargos in New Orleans and were returning with gold. The story is that Mason and his gang stepped out on the trail to rob Wetzel, but when Mason recognized him, he let him pass. The two had undoubtedly known each other from Mason’s days at Fort Henry. By this time Wetzel was no longer the teenager Mason had remembered but a living legend at his zenith. Given the name “Deathwind” by his Indian enemies, Mason understood that this was not a man to be trifled with. Sadly unknown to most, it must have been as dramatic a good guy/ bad guy confrontation as Wild Bill Hickcock and John Wesley Hardin or any others of the later American West.

In the absence of any really effective law enforcement, honest men formed into bands of regulators. Some were the same hard-eyed men that made up the militia of the Indian Wars. These regulators were a bit short on legal niceties but were quick with a rifle and rope. They began to make the climate of the lower Ohio unhealthy for outlaw types.

By 1800 Mason must have decided that the game at Cave-in-Rock was played out. He moved his area of operation from the lower Ohio to the Mississippi, generally headquartering out of Natchez. His depredations became so bad that in 1803 the governor of Mississippi put a $2000.00 “dead or alive” reward on his head. Though that may not sound like much by today’s standards, $2000.00 represented nearly four years of salary for a skilled workman of the period. It would not only attract anyone brave or desperate enough to tangle with a killer of his repute, but it would also get the attention of any would-be Judas in his gang.

The reward had the desired effect. Mason’s end came in a drama worthy of Hollywood. Two seemingly minor criminals were being held under arrest in Natchez. They offered, if released, to bring in Sam Mason. Desperate to be rid of his menace, the authorities agreed. A few weeks later the outlaws did return, with Mason’s head rolled in a ball of clay. The most credible story that comes down about the event is that the two men had offered to join Mason’s band. Mason, hunted, desperate, and in dire need of more men, took them in. At an opportune moment his new confederates tomahawked and beheaded him. The head was positively identified as Mason’s, and the two men were briefly hailed as heros. The local government did not have enough cash on hand to pay the reward, so the men had to wait for a few days.

While they were waiting, suspicion about the two men began to grow. That suspicion was confirmed when a passing boatman identified the mysterious red- headed stranger as none other than Wiley Harpe! Harpe and his companion, later identified as Mason confederate James May, were tried and hanged in February of 1804.

American Wild West historian Paul Wellman would later refer to Sam Mason as “the first real genius of outlawry on the frontier.” John James Audubon would write of Mason in 1815: “The name of Mason is still familiar to many of the navigators on the lower Ohio and Mississippi. By dint of industry in bad deeds, he became a notorious horse stealer, forming a line of worthless associates from the eastern part of Virginia (a state greatly celebrated for its fine breed of horses) to New Orleans, and had a settlement on Wolf Island, not far from the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi, from which he issued to stop flatboats and rifle them…His depredations were the talk of the whole western country.” (1)

If the modern reader cannot conceive of just how dangerous a menace Mason was during his lifetime, perhaps a comparison to more modern criminals will help put this into perspective. Al Capone was considered a mad-dog killer, even by his New York Mafia contemporaries. That’s quite a testimony coming from the folks who ran an organization called “Murder Inc.” Capone’s score of eight victims killed in the St. Valentine’s Day massacre still stands as a modern record. With Mason’s murders of entire families and boat crews, it is most likely that he not only bettered Capone’s single event record but may have done it several times. His victims must have numbered well over 100. Studying the matter strictly by the scorecard, no outlaw of the American Wild West approached these numbers. Even someone like the much better known Jack the Ripper appears an amateur. The Friendly City has never produced another badman of Mason’s stature. No Wheeling outlaw of the past or present era ever came close to running such a bloody tally.

Copyright Joseph Roxby August, 2002

1) Wellman, Paul I,. Spawn of Evil, Garden City, New York, 1964

Other Suggested Reading

The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock by Otto Rothert

and

The Outlaw Years by Robert Coates