Pigeons. Doves. Rats with wings. All names for Columba livia— our humble city pigeon. Have you seen the flock of pigeons around town? Sometimes they are on a sunny roof, surveying the scene below. Other times they are swooping down to the ground, looking for tasty snacks in a peaceful setting.

If you’ve wondered why these birds seem to prefer hard cityscapes to parks or forests, you’ll look to how they evolved. Pigeons, or Rock Doves, originated in North Africa and the Mediterranean where hard surfaces by way of cliffs and ledges instilled an affinity for hard surfaces.1

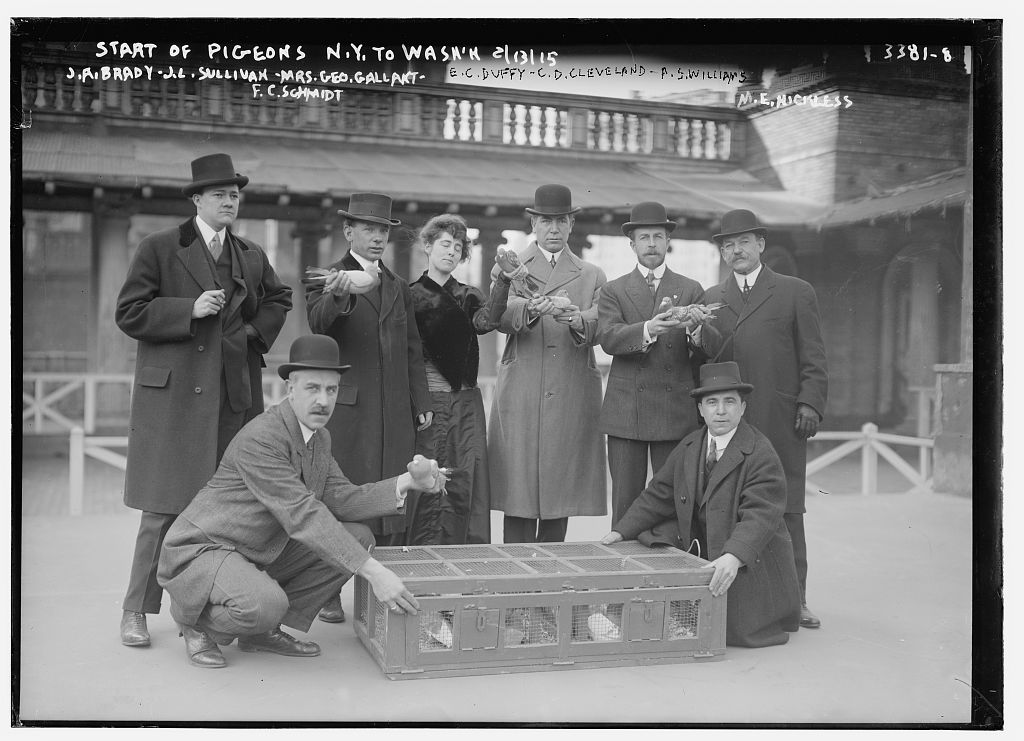

They were also raised by humans for food in Mesopotamia (ancient Middle Eastern civilization, about 5,000 years ago), and their “homing” capabilities were utilized by Greeks to share results of some of the first Olympic games. 2 Eventually, these birds went from delivering the results of sporting events to becoming the main event themselves!

Pigeon Racing Through the Years

Pigeon racing, in the simplest explanation, is the act of releasing a trained pigeon away from their home and measuring which racer returns first. Pigeons battle predators, weather and their own stamina as they aspire to return to their roost.

Because Wheeling has been there and done that, there is of course a pigeon racing past in the Friendly City.

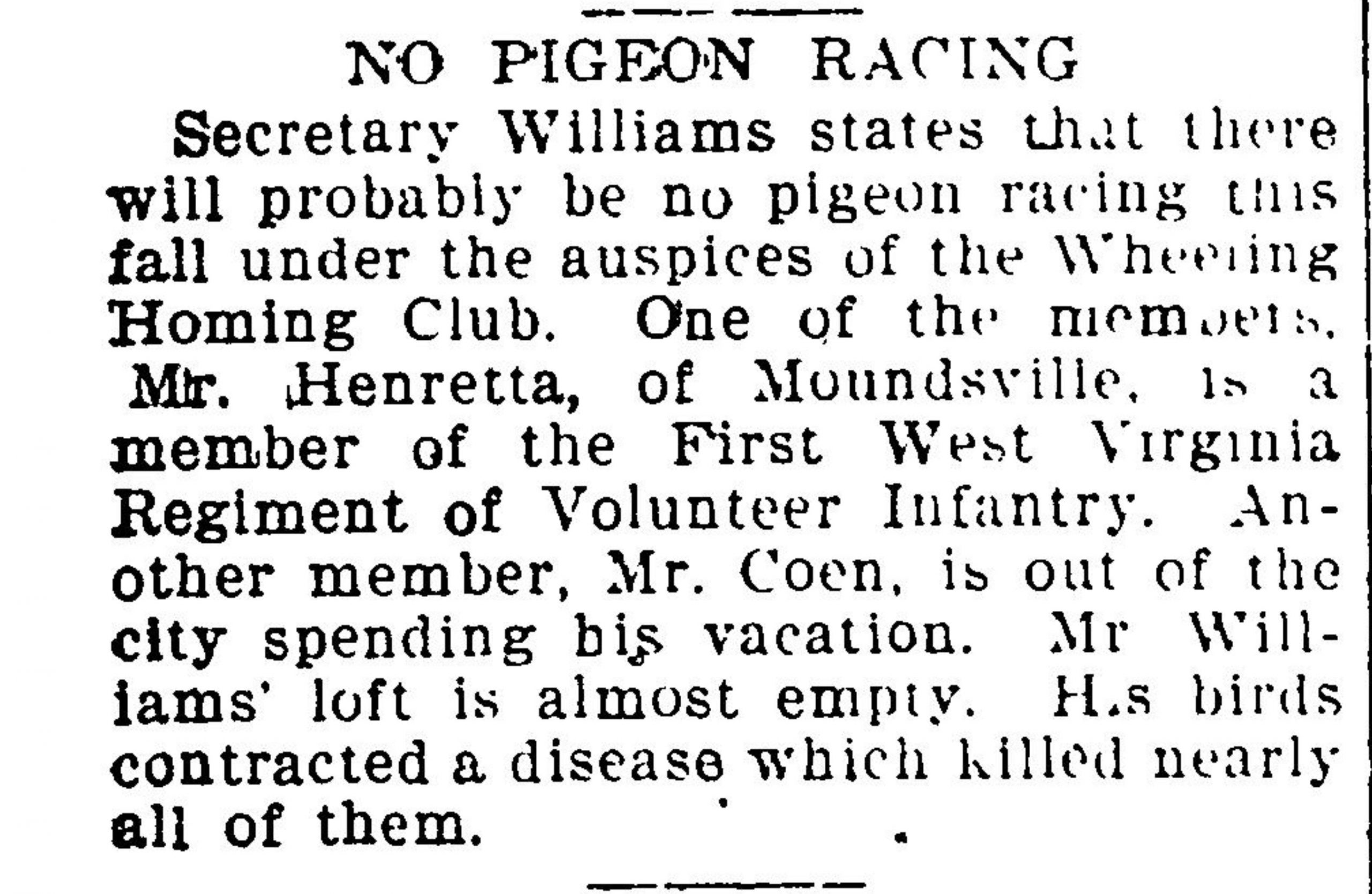

The 1898 Wheeling Daily Register bears evidence of some of the city’s earliest pigeon pursuits. The Wheeling Homing Club suspended activities when three of its members were unable to participate, leading the reader to wonder just how many were in the club to begin with. 3

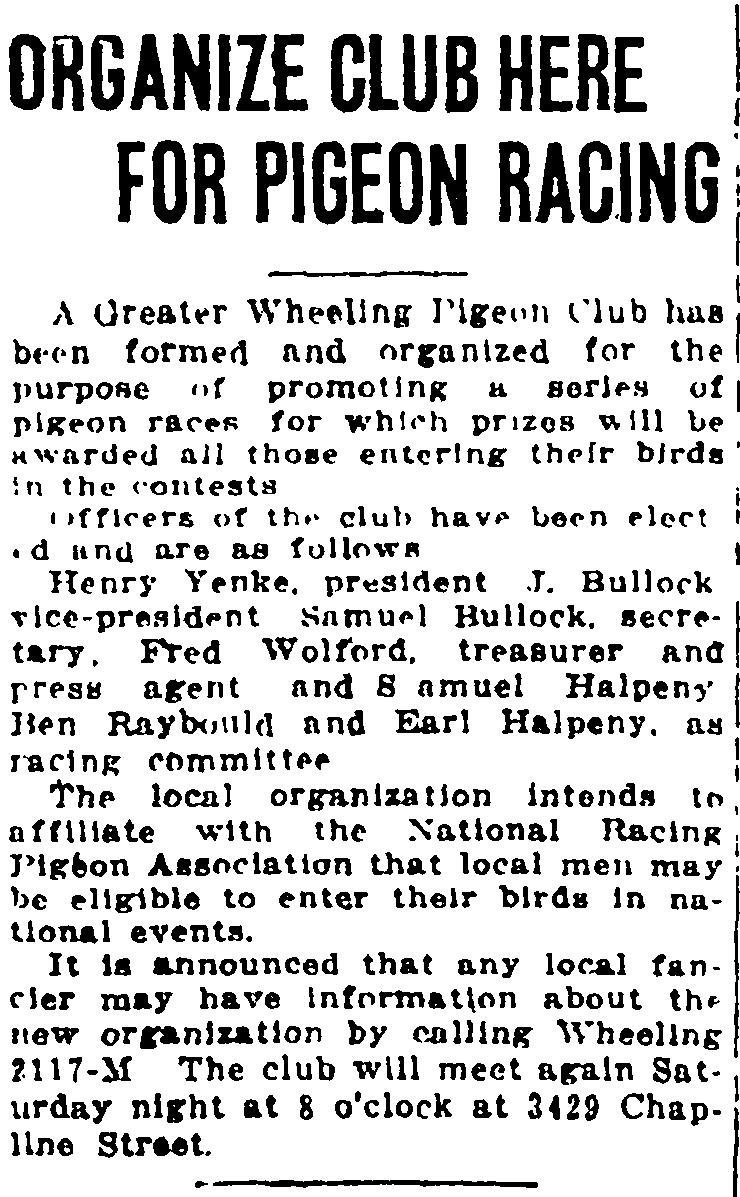

In 1923 the locus of pigeon fancying shifted to South Wheeling, with the formation of the Greater Wheeling Pigeon Club. Their listed meeting place is 3429 Chapline Street, home of their secretary, Samuel Bullock.4

By the 1950s, racing activity shifted to Benwood and neighboring Ohio communities.

Local Boy Does Good

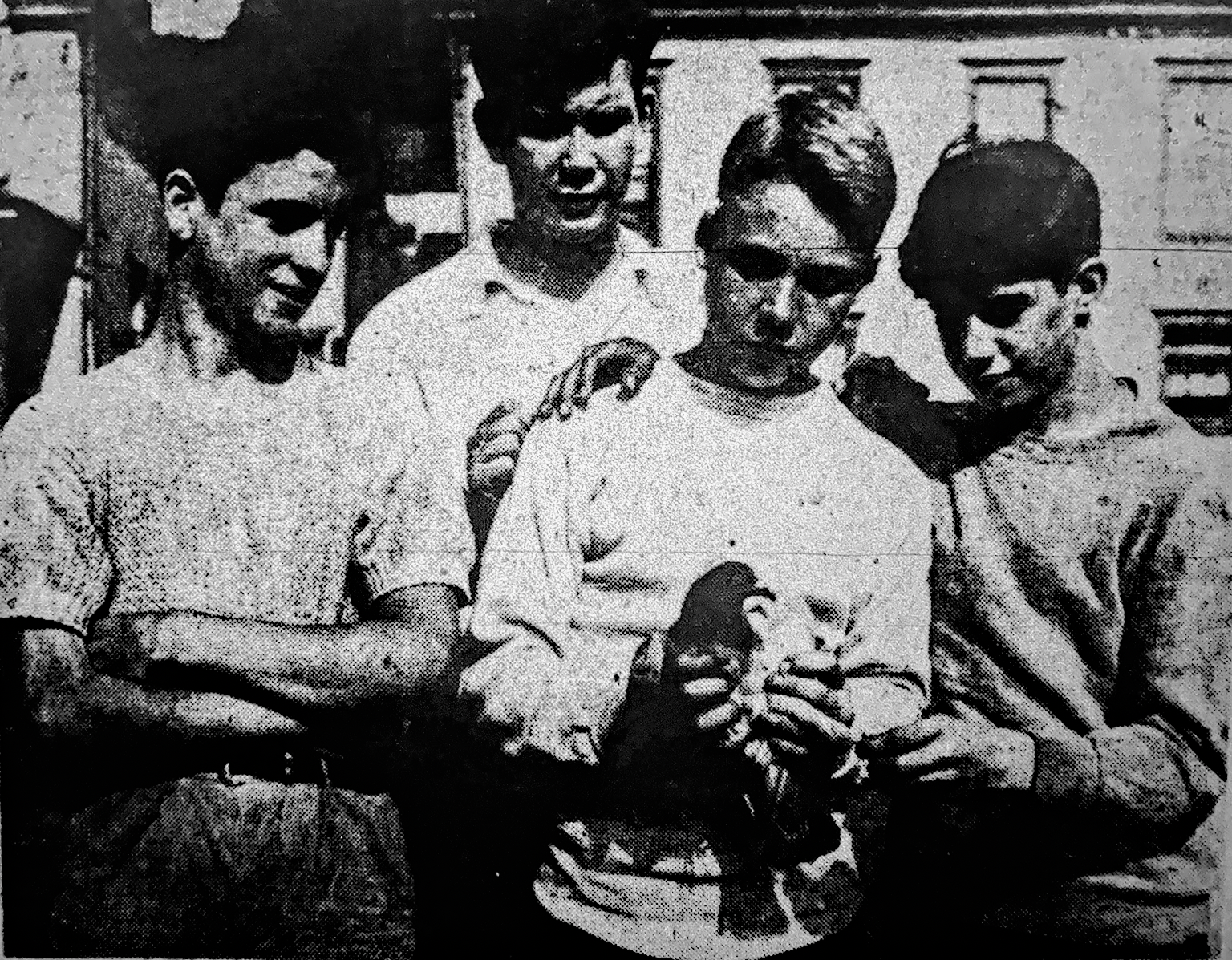

Long before Bob Weir made his name as a skilled craftsman and devoted preservationist, he was a 13-year-old boy from North Wheeling with a paper route. On one hotter-than-average August day, “Bobby” Weir and his friends came across a pigeon “ambling rather confusedly” along the sidewalk. 5

The boys noted the identification bands on the ankles of the bird and contacted the Wheeling Intelligencer as to what to do next (remember, this was before the internet!). Luckily the paper was able to contact a “homing pigeon raiser and authority,” Clyde C. Wilson, who advised that the bird was likely from Pittsburgh, and could find its way back with a little rest.

With no further mention of Bob and his pigeon in the Intelligencer, one can only assume that the boys were able to safely care for and release the bird.

Bird Racing Today

Although the popularity of pigeon racing has waned, there are still enthusiasts who raise and race birds. As such, pigeons will still occasionally be downed by weather or other impediments.6 While racers can better keep track of their pigeons with GPS and the internet, the birds have not fundamentally changed, and like before, should be able to make it home with a little bit of rest and relaxation. The American Racing Pigeon Union has a page on its website dedicated to the identification and care of downed birds.7

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.

References

1 Bittel, Jason. “Ever wondered why cities have so many pigeons?” the Washington Post (Washington D.C.), June 9, 2019. From https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/kidspost/ever-wondered-why-cities-have-so-many-pigeons/2019/06/07/ffad4918-83b9-11e9-95a9-e2c830afe24f_story.html

2Norman, Jeremy. “Using Carrier Pigeons for Communication in Antiquity.” Jeremy Norman’s History of Information. From https://historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=3961 Accessed December 28, 2021.

3 “Marshall County Spanish-American War Soldiers’ Obituaries” From https://www.wvgenweb.org/marshall/spnamwar-obits.htm. Accessed December 28, 2021.

Houston Henretta, was a 23-year-old from Moundsville who enlisted with the 1st West Virginia Infantry. He died nearly a month after this notice appeared in the Wheeling Register. His cause of death was Yellow Fever, a viral disease spread by mosquito bites; not to be confused with Malaria. According to the enclosed article ‘A Soldiers Funeral’ he was the first from Moundsville to die as a result of the Spanish-American War.

4 Callin’s Wheeling City Directory, 1924. R.L. Polk & CO. Publishers.

5 Wheeling Intelligencer, August 26, 1949

6 Ownes, Charles. “Lost Racing Pigeon Found in McDowell,” Register-Herald (Beckley, West Virginia), December 14, 2017. From https://www.register-herald.com/news/lost-racing-pigeon-found-in-mcdowell/article_224704e2-6d1c-5cf0-ae5b-56e407852417.html

7 “Reading the Bands.” American Pigeon Racing Union, Inc. Accessed December, 21, 2021. From https://www.pigeon.org/pages/lostbirdinfo.html