It all began with an oil painting hanging over the circulation desk in the library at Hanover College in Indiana. Jessica Whitehead admired it for years while pursuing an arts history degree at the college, but she never bothered to ask who had painted it.“Just like [Harlan] Hubbard on one of his many trips down the Ohio River, I came with the water from Wheeling and was mysteriously compelled to stop at this beautiful little part of the world near Madison, Indiana.” — Jessica Whitehead

That all changed when a requirement for her degree was to design and hang her own art exhibition using items from the college’s art collection. The artist, it turned out, was Kentucky native Harlan Hubbard, and the particular painting in the library was a view of “The Point” — a name given by the community to two large bends in the Ohio River. This very view was a major selling point for Jessica when deciding just where, exactly, she wanted to go to college. She describes the view of The Point “as uniquely breathtaking.”

That all changed when a requirement for her degree was to design and hang her own art exhibition using items from the college’s art collection. The artist, it turned out, was Kentucky native Harlan Hubbard, and the particular painting in the library was a view of “The Point” — a name given by the community to two large bends in the Ohio River. This very view was a major selling point for Jessica when deciding just where, exactly, she wanted to go to college. She describes the view of The Point “as uniquely breathtaking.”

Hanover College’s campus sits on top of a hill that overlooks The Point, and Jessica was drawn to that beauty so much so she decided to make Hanover her temporary home. Her assignment kickstarted her interest in Hubbard, which has led to being involved in several projects on Hubbard’s life and art, including a book proposal on his prolific work in watercolor that is expected to be published in 2020.

Jessica has been around art her whole life, and she knows she has been fortunate to spend a lot of quality time with her parents over the years — a benefit to being an only child. Both of her parents are college professors, and the Whitehead household was always full of art and music, as were the travels she took with her family.

THE MAGIC OF THE MOUNT

Jessica was a student in one of the final classes to graduate from the Mount de Chantal Visitation Academy, a Catholic all-girls school in Wheeling, West Virginia, which, to the dismay of many, was torn down in 2011. Jessica attended the school from 2002-07, transferring from Triadelphia Middle School in eighth grade.

The Mount was a magical place for Jessica. When asked how her time there shaped her into the person she is today, she said she thinks about her time there nearly every day.

“I think all of us who attended school there have different things that we feel the experience afforded us, but perhaps the most palpable legacy the Mount left to me is endlessly searching for creative solutions to common problems. No one — not the teachers, administration, sisters or other students — expected any less from us just because we were young girls. As an adult woman now, I see how rare that sort of trust and confidence can be for many girls, especially for those who are ambitious and creative. It makes me that much more grateful for my experience. The Mount taught us every day that we were capable, that our voices were valued and that our accomplishments would be remembered, just like those of all the women who had sat in those classrooms before us.

“The Mount taught us every day that we were capable, that our voices were valued and that our accomplishments would be remembered, just like those of all the women who had sat in those classrooms before us.” — Jessica Whitehead

“That kind of encouragement goes a long way to mold young women who want to work hard and aren’t afraid to ensure that their contribution to improving their world — on a wide-spread or local scale — is respected.”

Jessica explains that the Mount gave the students the freedom to succeed or fail based on their own willingness to make themselves the best they could be. “Be who you are and be that well” are the words of St. Francis de Sales that were found printed on the Mount’s walls, on chalkboards and school T-shirts. It helped teach the girls that their future success depended on how well they could accept their unique abilities and use them to make their lives richer.

The Mount also gave Jessica opportunities to travel and receive cultural experiences that weren’t always available in Wheeling. “But more important, we were taught how to make our own cultural experiences wherever we were.” Jessica is currently the collections manager for the curatorial department at the Kentucky Derby Museum, a job she loves. Her education taught her to see any environment as having potential for the creative process.

“This has stayed with me, and has encouraged me to look at every opportunity and experience as a blank canvas. Even things that I never knew I would be interested in, like horse racing or a Kentucky sustainability advocate, became open space for my curiosity to roam. There is something intensely fascinating about almost any subject, and I think I owe that outlook to the Mount.”

MOVED BY HARLAN HUBBARD

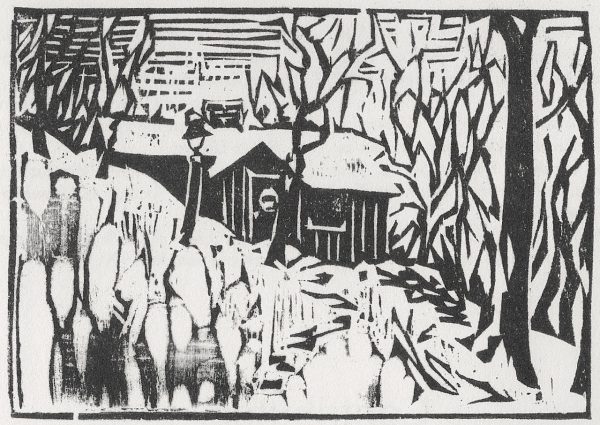

Harlan Hubbard was born in Bellevue, Kentucky, in 1900. His father died when Hubbard was a young boy and his mother moved him and his two brothers to New York City. Harlan took an interest in art and received his education at New York’s National Academy of Design and the Art Academy of Cincinnati, although he did not finish either program. He moved back to Kentucky in 1919. Harlan turned out a myriad of material throughout his life, including watercolors, works in oil, woodcuts, maps and drawings.

Harlan’s greatest muse was nature. Jessica explained that she has “enjoyed stepping into the shoes of even further iterations of Harlan that spring up like weeds as I read about him: Harlan the explorer, Harlan the environmentalist, Harlan the birdwatcher, Harlan the cartographer.” Hubbard was a writer and published two works in his lifetime: Shantyboat in 1953, and Payne Hollow in 1974. The publication of Hubbard’s Shantyboat is why most of us might know what a shantyboat is today.

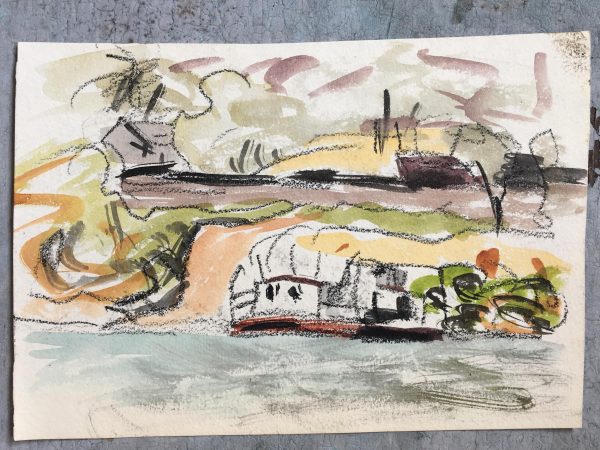

Hubbard often documented his surroundings in sketchbooks and journals as he traveled and observed the land and people around him in Kentucky. Hubbard took an interest in the “river people” of the Ohio River who lived in shantyboats, as there was a thriving shantyboat settlement close to Hubbard in Fort Thomas, Kentucky, called Brent. Hubbard had a painting studio in an old lumber mill within Brent, and he began observing the shantyboat people and became acquainted with some of them.

Many Americans during the 19th century and into the 1950s were living in homemade shantyboats along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, which was a solution for displaced people in rural areas who couldn’t afford other options. Shantyboats were found along the riverbanks of industrial American towns, and many working-class people lived on the water and worked in the urban factories, calling the river their home. Living in these free boats (with sometimes a total of three rooms) was better for many than paying rent to live in one room with several others in apartment buildings in the city.

By the time Hubbard became interested in the life of shantyboaters, it was becoming a slowly disappearing culture. Hubbard had long dreamed of writing a book about the river life. He was drawn to the simplicity of the river people’s lives and of being a part of the natural world. It wasn’t until he met his wife, Anna, who supported him and his dream to simplify his life, that he began to build his own shantyboat. The end result is their six-year journey on the river from Brent, Kentucky, to New Orleans, Louisiana, from November 1944 to April 1950, which is chronicled in his famous publication, Shantyboat.

“Looking back now, and thinking poetically, I think the reason Hubbard moved me as much as he did — and does — was because I felt part of his adventure,” Jessica explained.

“Just like Hubbard on one of his many trips down the Ohio River, I came with the water from Wheeling and was mysteriously compelled to stop at this beautiful little part of the world near Madison, Indiana.”

After Hubbard’s six-year shantyboat adventure, he and his wife settled at Payne Hollow, continuing to live a simple, frugal life away from mainstream society. The beauty that Jessica found while deciding where to go to college is the same beauty that made Harlan and Anna settle at Payne Hollow and build a home and live off of the land, with no electricity or running water, surrounding themselves with wilderness and art.

Jessica has been involved in several Harlan Hubbard projects since the first exhibit she curated at Hanover College. When she was working on her first project for school, she reached out to the executor of Hubbard’s artistic estate, Bill Caddell, and she credits her relationship with Bill and his wife, Flo, for the reason so many of her projects have been able to happen.

In 2013, the Caddells loaned Jessica some of Hubbard’s items for an exhibit to guest curate at the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft. “To my surprise, the exhibit had its closing date extended because it had gotten so much foot traffic. This made me happy because it proved to me that there were a lot of people in the region who either already loved Hubbard, or were ready to learn more. Eager to oblige a curious audience, I started thinking about some new projects that might get Hubbard’s story further out there.”

In September of 2018, Jessica and the Caddells submitted a book proposal about Hubbard’s work in watercolor, and the University Press of Kentucky accepted the proposal. It is expected to be published in 2020.

“I was absolutely thrilled because it had been at least a decade since the last publication about Hubbard, and a book would be a great vehicle to spread the ‘Hubbard Gospel.’”

Jessica is more than a little busy with her work and study of Harlan Hubbard. Last fall, she focused on Hubbard’s woodcuts at the Louisville Grows Healthy House Gallery that featured a printmaking demonstration and lecture, and among her research she ended up joining a collaborative group named Afloat: An Ohio River Way of Life — a group that plans to promote Harlan Hubbard and, as Jessica explains, “Ohio River-inspired exhibits and related programming that are springing up like weeds in Louisville and surrounding communities.”

This past January, Jessica gave a lecture at the Filson Historical Society where she focused on Hubbard’s perspective on the lost shantyboat culture of the Ohio River. Having grown up along the Ohio River in Wheeling, she felt a connection with Hubbard’s story, “especially when I learned that his early years were spent hitchhiking up to Pittsburgh.”

In her lecture, Jessica focused on what she called “Harlan the elegist,” and titled the lecture Recording a Vanishing World. She discussed how she saw Hubbard as having an elegy for the loss of place, the loss of people and the loss of principle. She sees Harlan’s writing as work that “stand[s] as counterpoint to the hubris of a world that is blind to the loss of its landscape and the people tied to that landscape.” Shantyboaters were left to the elements. The weather and the changing seasons were a constant struggle for those who lived on the river. The shantyboat communities were vulnerable to any natural disasters, such as the 1937 and 1945 floods. Some shantyboat communities would never recover from such disasters. The 1937 flood resulted in wealthier inhabitants of Louisville moving out of the flood plain, leaving the poorer communities to face challenges for years due to the mass exodus. Thanks to Hubbard’s novel, Shantyboat, he left behind information and knowledge about this disappearing culture for generations to come. Jessica’s event was standing-room-only, which only further confirmed her belief that “Hubbard is relevant, relatable and exactly what we need these days.”

Jessica continues to be busy with Harlan Hubbard projects. She’ll continue working on her book of Harlan’s watercolors due in 2020, and she assisted in an exhibit of his watercolors from the Bill and Flo Caddell collection at the Frazier History Museum, The Art of Drifting: The Watercolors of Harlan Hubbard, on display through May 5. This is the largest exhibit of Harlan Hubbard’s work. One of the curators of the show, Peter Morrin, former director of the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, will write the foreword to Whitehead’s upcoming book.

“It has been so wonderful to share and discuss Hubbard with all of these collaborators and friends,” Jessica said.

THE ART OF JESSICA

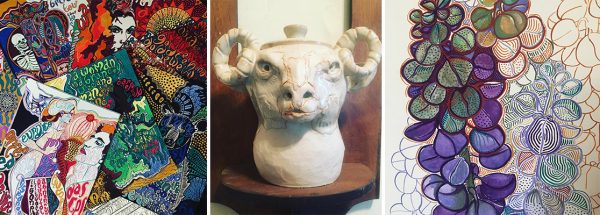

She also has her own art to keep her busy, and Hubbard has been a direct influence on her. She has been creating art her whole life, studying studio art in high school and college, mostly working with printmaking and painting with acrylics and oils, but began to try her hand at watercolors after working on her Harlan Hubbard watercolor book.

“At first, I started working on simple sketches, challenging myself to paint once a day, no matter how simply, in order to understand the medium better. I wasn’t quite prepared for the burst of productivity it sparked, but, since 2016, my art has been an integral party of my daily life, and I’ve somehow managed to build a body of work that has allowed me to open a side business selling it. I still work in watercolors nearly every day at home, and I recently picked up ceramics, another medium I have come to love.

“Art has truly sustained me through some very difficult years, and continues to sustain me through current, day-to-day stresses, frustrations and anxieties; the creative spirit — regardless of ability that merely comes to anyone with practice — is central to my emotional and philosophical well-being, and I believe that is so for every human in their chosen mode of expression.”

Jessica is inspired by outsider and folk art, which she explains as typically coming from people “whose voices traditionally haven’t counted in art history, or anywhere, who have a lot of emotional wealth to share” — such as people living in poverty and people with mental illness. She is also inspired by Medieval art and psychedelic art, and, like Harlan, draws inspiration from the natural world — her natural muse is predominantly animals.

Jessica’s future goals include someday starting a graduate program in art therapy. “If I can help anyone else to the benefits I’ve found in the creative process, I want to do it, and do it often!”

When reflecting on her time in Wheeling at Mount de Chantal and artist Harlan Hubbard as important mile markers in her life, Jessica realized there are similarities between the two that she had never really considered before.

“Those core principles the Mount instilled in me — creative problem solving, taking pride in one’s uniqueness and having the courage to live through it, and being curious about everything — are also core principles in Hubbard’s story.”

She’s not sure she would have understood Harlan Hubbard the same way if she hadn’t gone to the Mount, or maybe she wouldn’t value the Mount the same way if she never had encountered Harlan Hubbard.

“I’m not sure which one takes the greater credit, but I’m not going to split hairs about it.” Those of us following Jessica’s adventures in Kentucky can equally thank a Harlan Hubbard painting on the wall of the library, as well as the culture and community of Wheeling, West Virginia.

Jessica’s art can be purchased at her Etsy site, AlbionTygerDesigns.

• Kelly Strautmann lives out in the country of Cameron, W.Va., and proofreads in the city of Wheeling. She has a supportive and talented husband and two ridiculous daughters who keep her busy and full of love.