On July 2, 1864, George Washington arrived in Wheeling—65 years after his death. Well…his statue did.

During the Civil War, in June 1864, Union troops under Col. David Hunter burned most of the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia. VMI was a military academy with strong ties to the Confederacy; it also contained a state arsenal. While they avoided direct combat for most of the war, the VMI cadets had joined Gen. Jubal A. Early’s Confederate troops by the time of the burning. Before leaving Lexington, Union troops removed the bronze statue of George Washington that had stood in front of the Institute and shipped it off to Wheeling—the capital of the country’s newest state. 1

Washington’s Time in Wheeling

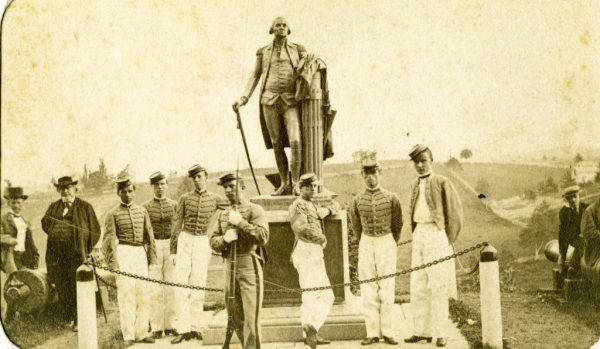

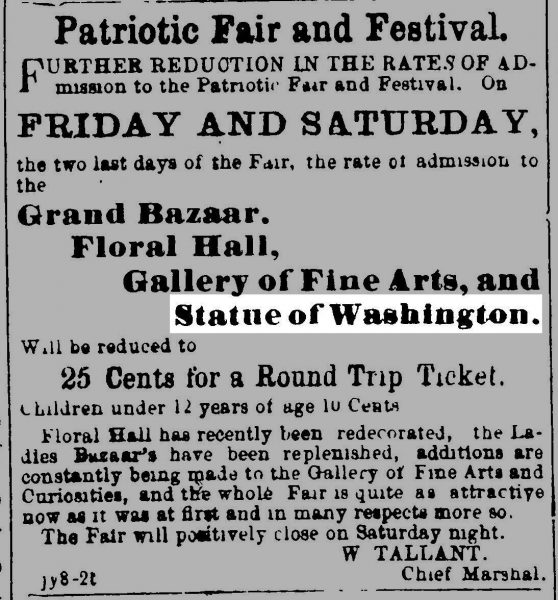

The statue arrived in Wheeling just in time for the Sanitary Fair—a festival held to raise money for the war effort. The newspapers quickly advertised the statue’s addition to the fair to entice readers to spend the entry money.2 The statue—created by Richmond-based artist William James Hubard—was a replica of the famous marble statue by Jean-Antoine Houdon that stands in the Virginia State Capitol.3 Houdon sculpted the original based on a life mask and Washington’s actual measurements, so for many Wheeling residents, this statue was the most accurate likeness they would ever see of the first president.

On the other hand, many Wheeling residents disapproved of Col. David Hunter and the circumstances that brought the statue to Wheeling. They thought his actions in Lexington—as well as other places—were shameful and fell outside the accepted rules of war. Wheeling’s Daily Intelligencer commented that taking the statue from Lexington was “an act of vandalism that must be objectionable to all right thinking people, irrespective of their hatred for the rebels.4

After the Sanitary Fair and the initial novelty wore out, the statue was placed in the yard of the Linsley Institute on Eoff Street where the state government was housed; today, the building is known as the “First State Capitol.”5 Originally, the army was supposed to send the statue to the West Point Military Institute in New York, however, it remained in Wheeling.

Old Memories Die Hard

After the Civil War ended, Virginia requested the statue be returned to VMI. David Hunter’s former chief-of-staff (and distant cousin), David Hunter Strother, was actually on the VMI Board of Visitors and helped facilitate the return.6 The West Virginia state legislature quickly agreed to the return…provided Virginia pay the travel costs.7

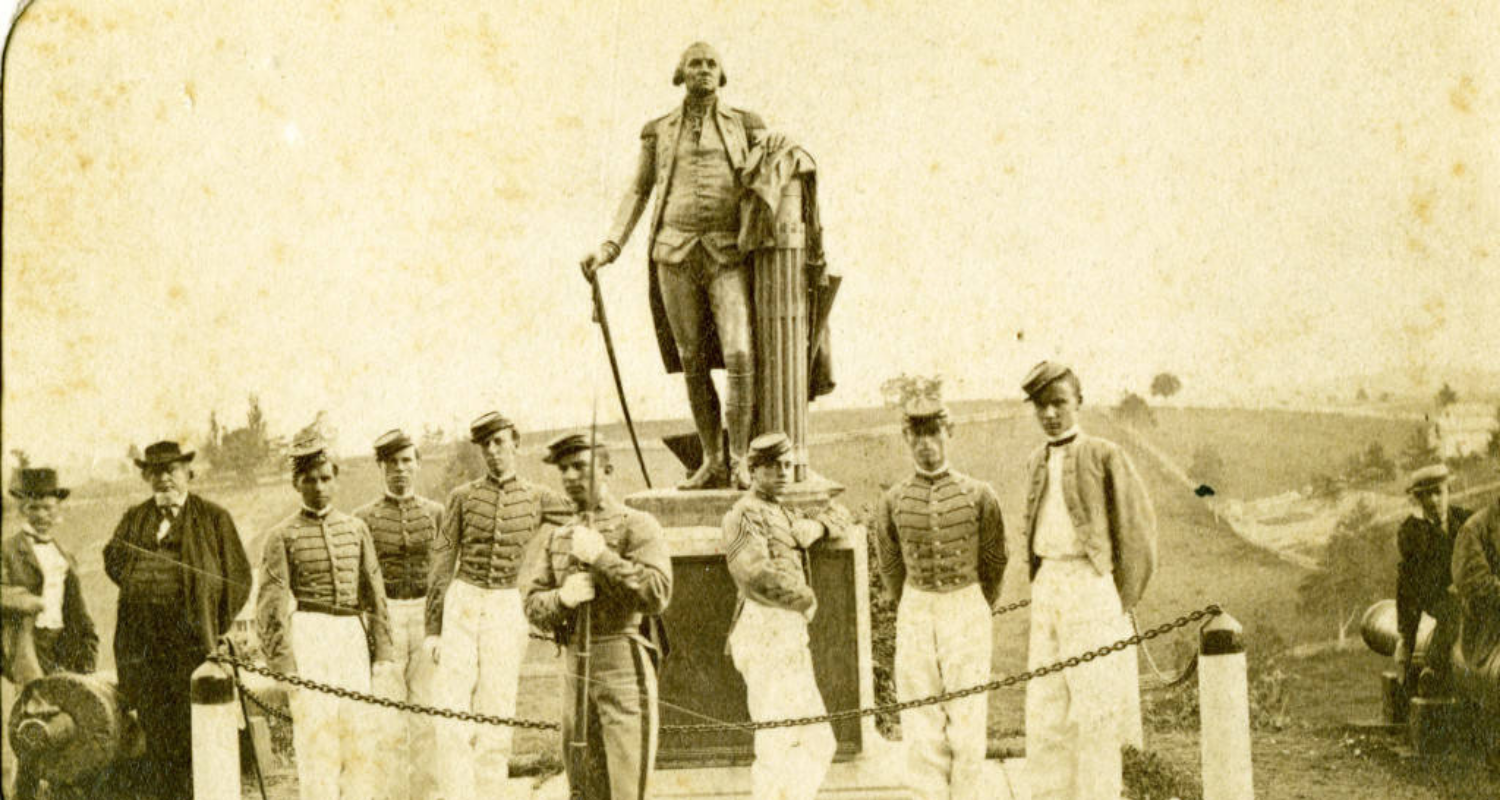

The statue was rededicated at VMI on September 10, 1866 in front of an audience of cadets, officials, townspeople, and distinguished guests. According to certain reports, Gen. Robert E. Lee was rumored to have attended, having recently accepted the presidency of the nearby Washington College.8 Gen. Ulysses S. Grant—who had, just over a year before, commanded the army that burned VMI—received an invitation, but had to send his regrets because he was traveling with President Andrew Johnson.9

Even though the statue was returned a mere two years after it was taken from VMI, it appears that Lexington has not forgotten its loss. In 2015, Margaret “Peg” Brennan—one of Wheeling’s favorite local historians—visited and toured VMI with several other Civil War history enthusiasts. The moment they arrived at the Washington statue, Margaret remembers how the tour guide’s face got red and his voice rose as he described the burning of VMI and how Union troops carted off the statue. She said he acted “as if it had happened yesterday,” and the Wheeling group quietly fell to the back of the tour group.10

Even though Washington’s short visit to Wheeling only lasted two years, it seems old memories die hard!

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “Statues and Monuments at VMI,” Virginia Military Institute Archives, accessed September 27, 2021, https://www.vmi.edu/archives/vmi-archives-faqs/statues-and-monuments-at-vmi/.; Jennifer R. Green, “Virginia Military Institute during the Civil War,” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020, accessed November 4, 2021, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/virginia-military-institute-during-the-civil-war.

2 The Daily Intelligencer, July 4, 1864, p. 2.; “Statue of Washington,” The Daily Fair Journal, July 4, 1864, Wheeling, WV, https://archive.org/details/dailyfairjournal1641na_0/page/n1/mode/2up.

3 “Statues and Monuments at VMI,” Virginia Military Institute Archives.

4 The Daily Intelligencer, July 4, 1864, p. 2.

5 Jon-Erik Gilot, “Unselfish Zeal: Wheeling’s 1864 Sanitary Fair,” Upper Ohio Valley Historical Review 41, No. 2 (Spring 2020): 28.

6Wheeling Civil War 150 Committee, “How George Washington Became Civil War Spoil,” The Intelligencer, July 13, 2014, accessed November 4, 2021, https://www.theintelligencer.net/news/top-headlines/2014/07/how-george-washington-became-civil-war-spoil/.

7 The Wheeling Daily Register, January 17, 1866, p. 1.

8 “Re-inauguration of the Statue of Washington at Lexington, Va.,” Staunton Spectator, September 18, 1866.

9 “Further from the Lexington Celebration—A Fine Dinner—Numerous Speeches—The Cadets at their Fun—A Hop—General Grant’s Letter,” Richmond Dispatch, September 13, 1866.

10 Brennan, Margaret. Interview by Emma Wiley, October 8, 2021.