It was a rainy October afternoon in 1925 when Warwood became the site of a devastating train derailment. This disaster claimed the lives of three railroad workers, injured several others, and left the community reeling. Beyond the facts, the human element of this tragedy—the bravery, the loss, and the unanswered questions—deserves to be remembered. And one man, Emmett Campbell, watched helplessly as the horrific accident unfolded before his eyes.

The 1925 Warwood train derailment, though a forgotten piece of history, holds critical lessons about human error, technological shortcomings, aging equipment, and the resilience of the Wheeling community in the face of catastrophe; lessons that are still relevant today.

Warwood and the Rails in the 1920s

Railroads: The Lifeline of Wheeling

In the 1920s, railroads were the backbone of industrial life in Wheeling and its surrounding areas. Pennsylvania Railroad’s train No. 531, a mix of wooden and steel passenger cars, was a familiar sight, running regular routes between Pittsburgh and Wheeling. For many locals, the railroad was more than just a means of transportation—it was a vital connection to the wider world.

Although automobiles were becoming more common in the region, the railroad remained the better option for traveling to and from Pittsburgh. Cars were still relatively new, and the area’s road system was primitive—often unpaved and difficult to navigate. In contrast, the railroad offered a faster, safer, and more reliable way to travel, making it the preferred choice for Wheeling’s working class and others needing to reach the industrial hubs of the time.

Warwood: A Town on the Tracks

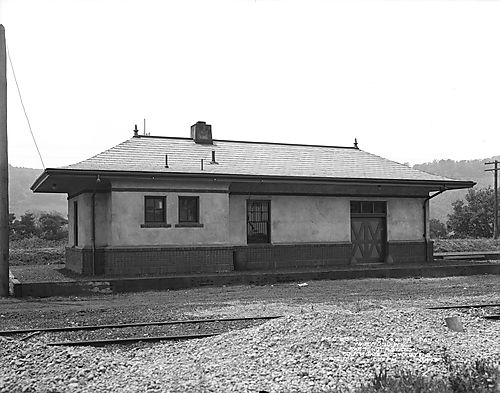

Just a few miles north of the accident site, the Warwood Pennsylvania Railroad Station stood proudly near the end of North 16th Street, not far from Garden Park. In the early 1900s, this station was more than a stop for trains; it was a hub of connection and industry, bringing life to Warwood and tying the community to Wheeling and the broader world.

The railroads weren’t just a backdrop to life in Warwood—they were the lifeblood. Workers at the Centre Foundry, near the site of the 1925 derailment, would have heard the constant rumble of trains, seen steam rise against the hills, and perhaps even waved to passengers passing by. Trains were a daily presence, weaving together the town’s story with steel rails.

Today, those tracks are gone, replaced by the Heritage Trail, a serene path that invites reflection on a time when trains ruled the landscape. Walking along the trail, it’s hard to imagine the chaos that unfolded one rainy afternoon in October 1925. Yet, the memory of that disaster remains part of Warwood’s history—a stark reminder of the risks inherent in the railroads that once defined the town.

View to a Disaster

What Happened?

At 3:15 p.m. on October 14, 1935, Pennsylvania Railroad passenger train No. 531, heading southbound from Pittsburgh to Wheeling, derailed north of the Richland coal mine near Warwood. Traveling at an estimated 40–50 miles per hour, the train met disaster in an instant.

At the time, no one knew what had caused the catastrophic accident. Witnesses described the harrowing scene as the engine was sent flying through the air, landing in a ditch on the Centre Foundry’s property, followed closely by the baggage car. Chaos ensued—steam billowed from the wreckage, and flames quickly erupted, casting a scene of devastation over the small industrial area.

Emmett Campbell, a chipper at the Centre Foundry and a former brakeman on the Pennsylvania line, provided a vivid eyewitness account of the tragic derailment to a reporter from the Wheeling Register on October 15, 1925. His firsthand observations capture the chaos of the event:

“I had remarked that the train was late,” said Mr. Campbell. “I would say that it was at least five minutes late when the wreck happened. And another thing that I noticed was that the engineer did not blow his whistle as he approached the foundry yard. He had always sounded a blast or two just before crossing the switch into our yards, but he didn’t yesterday. I cannot say that the engineer was speeding to make up time when the wreck occurred. He usually passed our place at about 40 or 45 miles an hour.

Because he did not blow the whistle, the first time I noticed that the train was coming was when I heard a dull crash, probably like the engine leaving the track. Then I looked up quickly and saw the engine in the air. It was falling over, and the baggage car was coming with it. I could hardly believe my eyes. I looked away and then turned toward the engine again. There it was, on the ground by that time, with steam breaking out all over it, and I saw some flames coming out of the front part of the baggage car.

My father, Albert Campbell, works with me, and he saw the whole thing too. He called to Harry Hesse, draftsman, and Clarence Bierl, foreman in the foundry. And they ran out to the train. I went to turn in the fire alarm. The department did not respond at once, and I called up headquarters, being told that the trucks were on their way. But in the meantime I had gone over to the wreck and helped get the doors of the coaches open. My father, Mr. Hesse, and Mr. Biehl were the first to break into the coaches and look over the passengers.

Many were shaken up in the crash, but so far as we could learn, only one passenger was really hurt to any extent. He had been cut on the face by broken glass in the first coach from the baggage car. The fire lasted only a few minutes. Clouds of steam were rising all about the engine, and I believe that the fire was smothered out by the time the fire department arrived. There was no need for firemen other than to aid in getting the dead out of the engine. And there was some good work done in that job, too.”

The Human Toll

Bailey was discovered on the floor of the cab, still gripping his shovel, though his body was badly bruised and scalded by steam.

The derailment claimed the lives of three railroad employees: Ollie B. Hays, the road foreman of engines from Wheeling; Michael Daugherty, the engineer from Steubenville; and Walter Bailey, the fireman from Jewett, Ohio. Five passengers and two crew members sustained injuries, but the true devastation lay in the loss of these men who perished in the wreck.

According to the eyewitnesses, the scenes were heartbreaking. The bodies of the victims were found in the wreckage in horrific conditions. The body of Hays was extricated from the cab of the engine, while Daugherty was found with his arms still wrapped around the throttle. His body had been horribly burned by the escaping steam, and his neck was broken. Bailey was discovered on the floor of the cab, still gripping his shovel, though his body was badly bruised and scalded by steam.

Rescuers faced tremendous challenges as they worked to recover the victims from the hissing steam and the avalanche of coal that had been thrown into the cab when the engine plunged into the ditch.

Panic spread as passengers scrambled to escape the wreckage. Many were thrown from their seats as the engine catapulted off the tracks. Some leapt from windows, dragging luggage with them, while others were too stunned by the shock to move. Despite the panic, many found their way to safety—fueled by instinct and the swift actions of nearby rescuers. By the time help arrived, the wreck had become a scene of twisted metal, splintered wood, and fiery devastation, all playing out against the backdrop of a small town.

Uncovering the Cause: What Went Wrong?

How the Tracks Led to Disaster

The railroad in this area was a single track controlled by signals and manual switches, designed to manage train movements safely. A switch–a section of track that allows trains to change paths–was the focal point of the accident. This particular switch, located near a factory, was on a slight downhill slope leading into a flat area. Unfortunately, it became a deadly hazard when an earlier freight train passed through.

According to the findings of the Interstate Commerce Commission report that was published a year after the accident, the freight train, carrying a hopper car with a damaged mechanism, unknowingly set the stage for disaster.

A Chain Reaction of Failures

The earlier freight train had stopped near the switch, and when it moved again, a loose hanger from its aging hopper car damaged the switch mechanism. Broken pieces of the hanger were later found at the accident site, confirming this chain of events.

What made this incident even more devastating was the failure of the signal system to detect the problem. The train’s crew had no reason to suspect the danger lurking ahead. By the time the locomotive reached the damaged switch, it was too late. The engine vaulted off the tracks, dragging the baggage car and coaches with it, into chaos.

Was This Accident Preventable?

The accident revealed troubling vulnerabilities in the railroad’s equipment and inspection protocols. The dragging hanger came from a poorly maintained hopper car, where the doors were not properly secured by the winding gear. This oversight wasn’t unique but rather a known issue with older models. The ICC report urged the Pennsylvania Railroad to conduct stricter inspections of outdated cars to prevent similar tragedies in the future.

Despite these findings, no individuals were held responsible for the derailment. The incident instead served as a grim reminder of how small maintenance failures and outdated equipment could combine into a deadly chain reaction.

Preserving the Story: Remembering the Warwood Derailment

The Warwood train derailment of October 1925 remains one of the most harrowing events in Wheeling’s history. It wasn’t just an accident—it was a tragedy that claimed lives, left families devastated, and tested the resilience of an entire community.

Honoring the Past

In the aftermath of the tragedy, residents of Warwood and Wheeling came together in ways that truly honored the lives lost. While the official investigation focused on the technical details, the compassion and selflessness displayed by ordinary citizens was pivotal in preventing further loss of life.

The lives of the railroad workers—Ollie B. Hays, Michael Daugherty, and Walter Bailey—were more than just those of employees; they were integral members of their community whose loss sent ripples of grief through Warwood, Wheeling, and beyond.

Heroes Amid the Chaos

Emmett Campbell became an unexpected hero that day. After seeing the engine crash onto the foundry’s property, he immediately called the fire department to report the blaze. Despite delays in the fire trucks’ arrival, Campbell didn’t stop there. He worked alongside his father, Albert, Harry Hesse and Clarence Bierl, to break into the damaged train cars and assist passengers.

Their efforts were swift and selfless. Campbell described how the fire was mostly smothered by steam by the time the firefighters arrived, but there was still work to do. He and the other rescuers helped free injured passengers and retrieve the bodies of the crew from the wreckage. Their bravery in the face of danger highlighted the resilience of Warwood’s people during one of their darkest moments.

The derailment was not just a story of loss but also of extraordinary courage and community spirit. The actions of Campbell, his colleagues, and the local authorities showed the strength of Warwood in the face of heartbreak. Today, their heroism reminds us of the importance of remembering and honoring those who came before us.