“Dominick,” called out the old man who sat atop the wooden playground structure where children spent warm weather afternoons spinning a toy steering wheel and pretending to be riverboat pilots. “I haven’t seen you around for a long time. Come sit.”

Dominick Carey seemed to float up past the swing and over the climbing net to the old man’s side on the wooden deck of the children’s playset and settled in. It was pitch dark, and a chill arose from the nearby Ohio River. The two old acquaintances didn’t seem to mind the dark or the cold but Carey was obviously agitated as they sat together in the Water Street playground near Wheeling’s Heritage Port.

“I get antsy on nights like this,” Carey said. “It was just like this on the night I took my tumble into Wheeling Creek.”

“I know what you mean,” the old man replied. “Back when the trains came in here, and I’d step outside at night for a smoke, the river had that same shimmer of light you can see now. See it? Over there? I think it’s coming from something on the Island. Maybe from the racetrack, the tabernacle or the fairgrounds.”

The old man was wearing a kind of uniform. There were brass buttons on his jacket, and there was a Pennsylvania Railroad patch on his left shoulder. Carey was dressed for more physical work. He had muddy boots, and his coat was soiled and ripped.

“I wouldn’t know,” Carey said, picking at the sleeve of his soiled coat. “I guess you spend most of your time out here since the station burned down.”

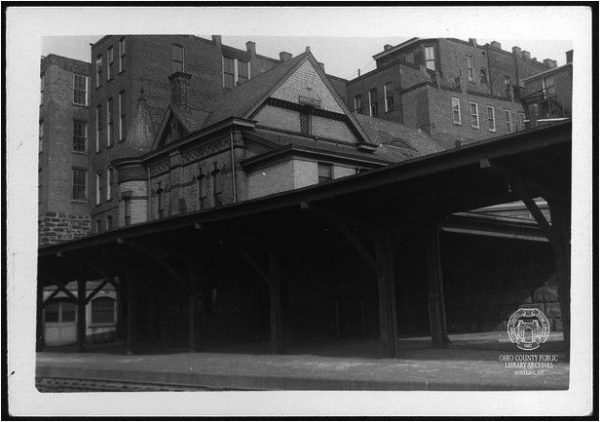

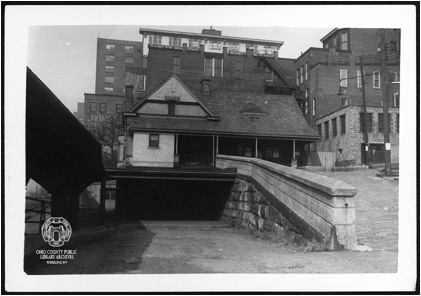

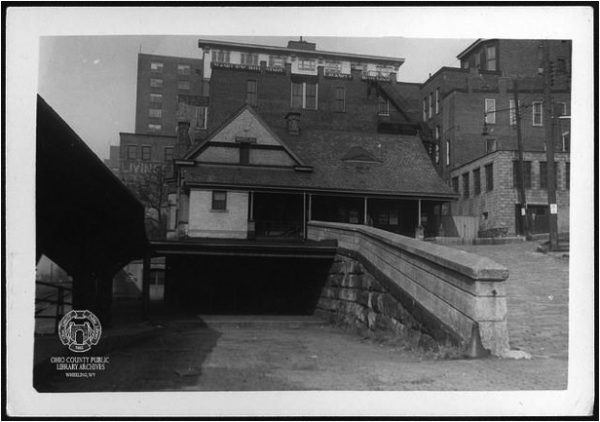

He gestured toward a grassy empty space next to the playground. All that remained of the old Pennsylvania Railroad Panhandle Depot was a concrete wall that featured a widow with rusty steel bars in it.

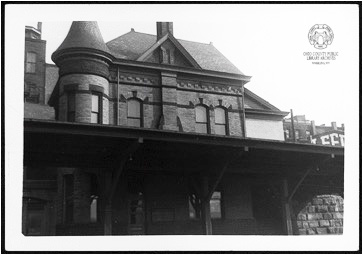

“That was a great building. I always liked that brick turret. Too bad about the fire.”

“That fire was set on purpose in 1969,” the old man said becoming agitated. “It may not have been a train station anymore when it burned, but it was certainly a place worth watching. Them young kids had something good going on in the 1960s although can’t say I was particularly a big fan of their music in those days. They called it the Equinox, and it was some kind of coffee house and music place. They sure didn’t deserve to have them drug fellas torch the depot just because the kids didn’t want drugs sold on the premises.”

“Don’t know nuthin’ about drugs,” Carey said. “In my day you took a snort of whiskey from the bottle in your lunch pail and minded your own business.”

“I figured you was a bit drunked up when you fell in the creek,” the old man said.

“No way,” Carey said. “I was shoved off that Main Street Bridge we were building over Wheeling Creek in 1892. I had me an argument with another worker from Wetzel County over a woman, and he done it. Nobody ever found my body neither. Been hanging around the riverbank here in Wheeling ever since.”

“I worked the parcel package room in the depot till my heart attack in 1905,” the old man explained as he scratched his white hair. “It happened right over there. One moment I was sorting packages, and next thing I know I’m wandering around the main floor of the depot, and nobody can see me.

“The Pennsylvania Railroad decided to stop running passenger trains through Wheeling, and that’s when they closed down the depot. It must have been sometime in the 1950s or so. I don’t remember as good as I used to. The place sat empty and sad for quite a few years till that coffee house started up.”

Domenick shifted uncomfortably. He felt like he probably had had this conversation before over the previous 80 years or so. He just couldn’t remember.

“Besides, that coffeehouse business, what would you say was the most interesting thing you ever saw here?” he asked.

The old man paused and thought for a while.

“Well, that flood in 1907 was a close call,” he said. “It rained like hell for 48 hours. The river came up fast after that. It crested at 50 feet on March 15. There was an engine parked right over there on the main track. Once they seen the water was comin’ up, a crew had to get out there fast and put the boiler out. If they hadn’t, when the water did come up, there would have been an awful explosion, and a lot of people would have probably got killed.

“There were a lot of Syrian immigrants who lived in what they called Papermill Alley then. More than a dozen of them died in the flood. In the middle of all that, there was a gas explosion, and the Warwick Pottery Plant burned almost all down. It was a real mess.”

They talked then at length about the busy times in Wheeling during World War II when the railroad was at its busiest transporting products made in the Ohio Valley mills and manufacturing plants, soldiers to and from the coast where they went off to war, and civilians to visit relatives or take care of business.

“There sure was a lot to watch in those days, but it just got slower and slower after that war,” the old man said. “Till that time the Freedom Train rolled in.”

“What’s a Freedom Train?” Carey asked.

“Well it was 1947,” the old man explained. “After we won that war, that there President Truman wanted everybody to stop and think about what it means to be an American. That Truman fella, he loved trains so he came up with the idea of having this big super train go around all over the country and invite folks inside where they could see all these famous documents and papers that are important to American history. I heard before it was finished, it traveled 37,160 miles all around the country and was the only train ever to operate in every state running on the tracks of 52 different railroads. They say more than three million people went aboard during 326 different stops at cities and towns all over America. Some folks waited in lines up to six hours to go aboard.”

“What sort of documents?” Carey said.

“They was all original documents,” the old man answered. “I know cause I seen ’em. There was 127 different pieces of history on that train. There was a letter from Columbus about his first voyages, a copy of the U.S. Constitution, a version of the Magna Carta. …”

“The magna what?” interrupted Carey.

“Nevermind. There was letters from Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Andrew Jackson and old Ben Franklin; Paul Revere’s original commission as a messenger; the Bill of Rights; the Declaration of Independence; the Emancipation Proclamation; and the surrender papers from the Japanese. I could go on and on. It was the darndest collection of important papers you ever could imagine.”

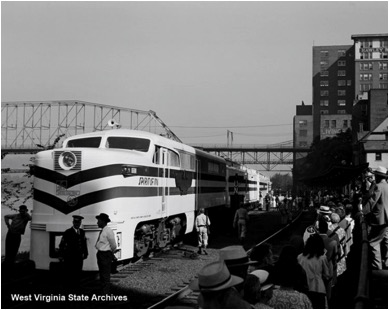

“Well sir, that Freedom Train, rolled in here to the Panhandle Station at 10 a.m. on the dot on Sept. 14, 1948, and I never saw nuthin’ like it. It was one of the first of them diesel train engines, and it was painted white with red and blue stripes on it. It had ‘Sprit of 1776′ painted just below the engineer’s seat. There was seven cars, and don’t you know that as soon as it stopped, a whole lot of U.S. Marines in full dress uniform popped out and took up positions around the train to help control the crowds. They was the fanciest soldiers I ever did see. And boy oh boy were there crowds.

“Them Marines was more than just guards. They helped steer the crowds in the train and kept folks moving sos everyone got to see all them important papers. I think that was the busiest I ever did see the depot. Seemed like there was people everywhere. They lined up all the way down Water Street to 14th Street. I heard later there was more than 11,000 folks who went through the train during the 12 hours it sat right here where we are sittin’ now.

“One of the strangest sights I ever saw was young girls plantin’ kisses on that train engine right below the ‘Spirit of 1776′ writin’. I actually saw a Marine have to wipe the lipstick off before the train pulled out.”

They chuckled over the image of girls kissing a train engine, and both men were then silent.

Carey broke the silence.

“All that’s gone now,” he said. “People are ridin’ bicycles where the tracks used to be, and here’s this crazy contraption that kids play on about where the trains used to stop. At least my old Main Street Bridge is still operatin’. Hey, you reckon folks still pay attention to that Constitution document and them other papers?”

“Some does, and some don’t,” the old man replied.

“Well I’ll be,” the old man interrupted. “Look at that little dog over there. Must be a stray. He looks just like a little dog I used to see back in the 1930s. He belonged to a blind man named Tom Minns. Pal, yeah, that’s it. His name was Pal, and he used to lead Tom all over town. They used to come down here together to pick up a batch of Cleveland Plain Dealers off the train. He sold them down at his store in South Wheeling. Heck of a guy. Here boy … here Pal.”

• Gerry Griffith was born and raised in Wheeling’s Elm Grove section. He pursued a career in journalism before working on Capitol Hill for then-Congressman Alan Mollohan in Washington DC. He returned to Wheeling and stayed nearly 20 years to work at Wheeling Jesuit University, Touchstone Research Laboratory, and, in Congressman Mollohan’s Ohio County office. He also worked for the West Virginia University Research Corporation. He lives near Pittsburgh where he works at the National Energy Research Laboratory. He is also a contributing editor to a national industrial research publication and dabbles in fiction writing.