It wasn’t a vivid dream, hallucination or even a tall tale.

In 1969, my buddies and I were bit players in the big showy history extravaganza that was performed with great zeal and enthusiasm at Wheeling Island Stadium in celebration of Wheeling’s 200th birthday.

I was 15 years old then, and the ensuing 50 years has taken a toll on my ability to recollect many of the details of Wheeling’s big bicentennial show — like the plotline or main stars of the production. But, some memories stand out and I clearly and fondly recall it as perhaps the biggest summer of fun I ever experienced growing up in the river city.

There was a rare excitement surging throughout the Wheeling in 1969:

• Banks published booklets dedicated to Wheeling’s history.

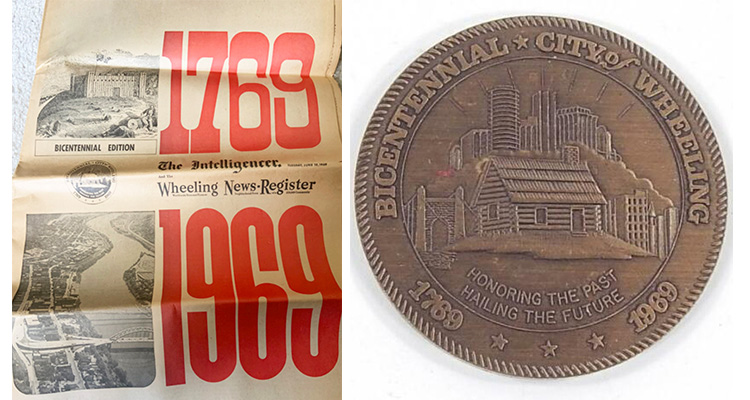

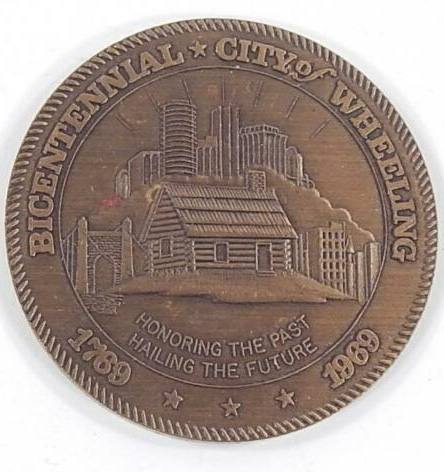

• The Wheeling News-Register published a massive supplemental edition loaded with stories about Wheeling’s 200-year history featuring long features about the Zane Family and the city’s record of industrial accomplishment.

• The Good Guys on WKWK talked about the bicentennial all the time in between playing top 40 tunes by the Fifth Dimension, Jackie DeShannon, the Grass Roots and the Temptations.

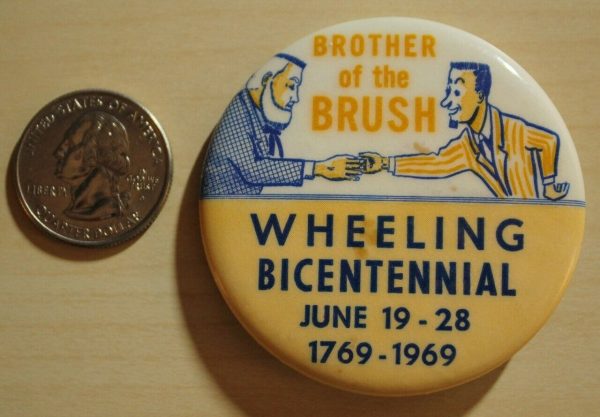

And, in perhaps the weirdest manifestation of bicentennial celebration hysteria, a great many men throughout the city, to the dismay of their wives no doubt, proclaimed themselves “brothers of the brush” and stopped shaving for the duration of the celebration. Some of the most conservative hippie-hating men I knew sported about town with long shaggy untrimmed beards just to be a part of the overall bicentennial festivities.

Against that backdrop, city leaders cobbled together the funding to put on the big bicentennial show. A cattle call for “extras” went out to civic groups and other organizations. My friends an I were members of the Wheeling Chapter of DeMolay — an international organization for young men named for Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar. That’s how we became summertime actors Wheeling’s show of the century.

Against that backdrop, city leaders cobbled together the funding to put on the big bicentennial show. A cattle call for “extras” went out to civic groups and other organizations. My friends an I were members of the Wheeling Chapter of DeMolay — an international organization for young men named for Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar. That’s how we became summertime actors Wheeling’s show of the century.

We were hesitant, curious and, like most teenagers, quite skeptical when we gathered for our first rehearsal inside the old Wheeling Exposition Hall on Wheeling Island. There was a loud flamboyant fellow who introduced himself as the New York City-based theater expert who was recruited to serve as director of the big show.

He had a Moe Howard haircut with long brown bangs and was dressed in blue jeans and a khaki long-sleeve shirt with epaulets that lent a military flavor to his appearance. He had a silk scarf tied around his neck. There were perhaps 100 of us in the cast or assigned technical duties, so he spoke to us through one of those police bullhorns that he held firmly against his lips with his left hand while gesturing wildly with his right hand. He began by explaining the enormity of our endeavor.

“This is going to be one of the biggest things you have ever been a part of,” he croaked through his bullhorn. “We are going to tell the whole history of Wheeling. We are going to convey it all through a script that we are finishing up now. There will be a narrator telling the story, and you people will act it out in little scenes. We are going to have big screens over at the stadium that will show movie clips that we will be making over the next few weeks. We are even going to fly a plane under the Fort Henry Bridge and film it from inside he cockpit. It’s going to be incredible.”

Over the next month, we diligently appeared every evening at 6 p.m. at the stadium for rehearsals. I remember it being excruciatingly hot on many of those nights as choreographers taught us how to square dance, assistant directors showed us the other bit parts we would play, and volunteer carpenters hammered away at the platforms and sets upon which we would perform our massive historical drama.

We were issued costumes and scripts, so we knew when to stand where and what to wear. We ran through our parts under the watchful eye of Mr. New York Director (never did get his name) who offered notes about how we should present ourselves.

I don’t remember there being any giant movie screens like the director promised, and there was, for sure, no film shown depicting an aircraft’s flight under the Fort Henry Bridge. But, there were other colorful parts of the overall set that gave a big production flair to our show.

Since we were bit players, and we rehearsed our scenes off to ourselves most of the time, we really didn’t have any feel for how the show fit together.

As teenagers, we were obligated and expected to execute sophomoric horseplay and display an annoying array of immature behavior, and we didn’t disappoint. Although we thought him a bit odd, to his credit, Mr. New York Director seemed to get a kick out of our humor and rarely yelled at us with his bullhorn. But when he did, he was unmerciful.

As teenagers, we were obligated and expected to execute sophomoric horseplay and display an annoying array of immature behavior, and we didn’t disappoint. Although we thought him a bit odd, to his credit, Mr. New York Director seemed to get a kick out of our humor and rarely yelled at us with his bullhorn. But when he did, he was unmerciful.

The evening rehearsals were always topped off by a visit to our favorite after event haunt — Elby’s on National Road. When we made our entrance and took our seats at a booth at Elby’s, we felt like New York Broadway stars at Sardi’s, except we drank Cherry Cokes and ate strawberry pie instead of cocktails and Delmonico steaks.

We were no strangers to the old Wheeling Island Stadium. I had been to nearly a dozen Shrine Circus shows in the venerable old facility and attended many high school football games there. The stage was established on the east side of the stadium field. The audience was restricted to the west side bleachers.

The show was performed over several evenings in savage summer heat. We peeked at the audience that first night just before show time from our ready positions behind the stage and were quite surprised to observe a sea of faces. We learned later that almost everyone we knew had managed to make at least one of the presentations that summer.

To this day, I can’t recall the details of the show or how it all worked. (I may never have known in the first place.) I do remember there were fireworks at the end of each show.

Today, it all seems like a fading dream. When getting ready to write this piece, I poked around the Internet in search of some evidence that it even occurred and I found nothing. It was like it never happened.

I do remember that after the final show, sitting at our usual table at Elby’s, one member of our little band of bit players said it best while summing up our bicentennial summer.

“I had a blast,” he said toasting our experience with one of Elby’s famous Cherry Cokes. “I may even stick around for the tricentennial.”

As of this year, we are half way there.

• Gerry Griffith was born and raised in Wheeling’s Elm Grove section. He pursued a career in journalism before working on Capitol Hill for then-Congressman Alan Mollohan in Washington, D.C. He returned to Wheeling and stayed nearly 20 years to work at Wheeling Jesuit University, Touchstone Research Laboratory and in Congressman Mollohan’s Ohio County office. He also worked for the West Virginia University Research Corporation. He currently lives near Pittsburgh where he works at the National Energy Research Laboratory. He is also a contributing editor to a national industrial research publication and dabbles in fiction writing.