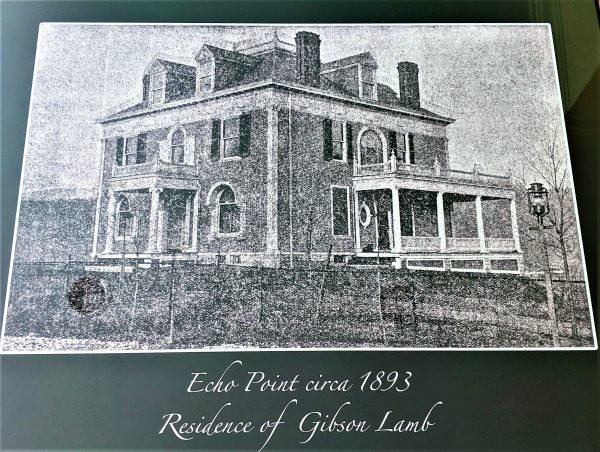

Tomorrow, if you stand where that photographer stood over 100 years ago, you’ll snap a remarkably similar photo during the annual Ogden Newspapers Half Marathon. Many things have changed, but Echo Manor is still there. Though the history of the building isn’t widely known, many people have had some sort of relationship with Echo Manor over the years.

THE GIBSON LAMB HOUSE

The story began on the John Woods farm in May of 1890. John Woods owned a large parcel behind the National Road; his farm would someday be known as Woodsdale. Woods sold 2.965 acres to Daniel Heiskell (for whom Heiskell Avenue would be named), who in turn sold a parcel to Mr. Gibson Lamb, the president of the Bank of Wheeling, who paid $2,000 for the land. In 1893, Lamb completed building his dream house, which would later be known as Echo Manor.

Gibson Lamb was born in 1840. He was the son of Daniel Lamb, one of West Virginia’s founders. A Quaker, Daniel Lamb moved to Wheeling with his family when he was 13 in 1823. He was educated there and eventually elected city clerk, followed by a job as treasurer of the Fire and Marine Insurance Company. He went on to be secretary and treasurer of Wheeling Savings Institution and eventually obtained his law degree.

According to researcher Kenneth R. Bailey, “When the secession vote split Virginia, [Daniel] Lamb was one of those who took the lead in crafting the government and constitution that would lead to the creation of West Virginia. He was a member of the first constitutional convention for West Virginia and a member of its legislature from 1863 to 1867. The first codification of West Virginia’s laws, known as the Lamb Code, was begun by Lamb, but finished by James H. Ferguson. In Prominent Men of West Virginia, Lamb was characterized as ‘rather a dull, heavy speaker but a careful and sound reasoner.’ He died in Wheeling.”

It’s unclear who originally designed the Gibson Lamb house, but it was built in the neoclassical style, characterized by symmetry. The prevailing style in Wheeling was Victorian, and a typical home might have a wrap-around porch on one side and a turret on the other. However, Echo Manor’s architectural style was influenced by the 1892 World’s Fair in New York City and became the first local home designed thusly. Not until the early 1920s did the rest of Wheeling move on from the Victorian style.

RENOVATIONS FOR CELEBRATIONS

In February of 1895, Gibson and Kate Lamb’s daughter, Elizabeth, married Clark Hamilton Jr. It was a highly anticipated event starring prominent Wheeling families, so it received considerable attention. The newspaper referred to it as a “pink wedding,” as all the flowers and decorations were done in that shade. Immediately after the ceremony at St. Matthew’s, the bridal party was driven by carriage back to Echo Manor for a lavish reception, while guests rode a special car on the Wheeling & Elm Grove Railroad. The wedding gifts were equally expensive, among them silver and cut glass.

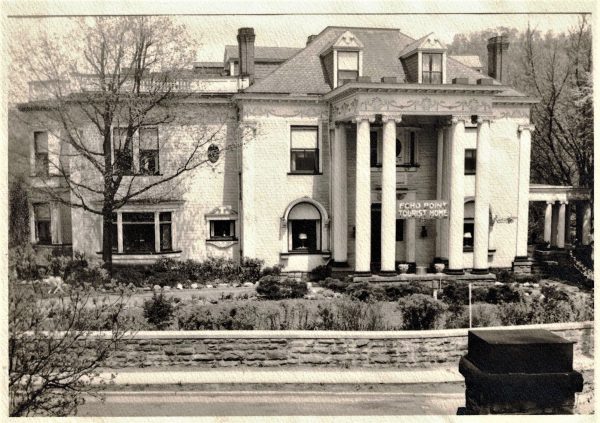

In anticipation of the event, the home was extensively remodeled with the addition of the west wing, the high columns and the circular porch on the east. The architect for the remodel was Edward Bates Franzheim, who also designed additions to Earl W. Oglebay’s mansion in 1900. (Franzheim was a relative of Laurence Woodward “Woody” Franzheim, another well-known local architect who would go on to design The Linsly School, among other buildings. Woody died in 2017.)

Sadly, Gibson Lamb enjoyed only a few happy years at Echo Manor. He died in 1899, and the house passed to Kate, who sold it in 1903 to Edward Franzheim’s brother, Charles W. Franzheim (b. 1853).

THE FRANZHEIM & STONE FAMILIES

Franzheim was president of the Wheeling Pottery Company, the first pottery works established in the city and the producer of LaBelle China. He also served as president of the Riverside Pottery Company, which began in 1899. Though these endeavors undoubtedly kept him busy, he was also vice president of the German Bank of Wheeling, vice president of the Franklin Fire Insurance Company of Wheeling, president of the Vance Faience Company in Tiltonsville (which manufactured art goods), and from 1889 to 1893, he was president of the Warwick China Company.

The Franzheims had been living on Front Street on Wheeling Island and sought to find a more upscale neighborhood. Franzheim resided in Echo Manor for nine years until his death. His wife, Lida, remained in the house until 1919 when she sold it to Edward L. Stone, the vice president of Stone & Thomas Department Store, and his wife, Elizabeth. After Edward’s death, Elizabeth stayed there until 1949 and then sold the property to Billy Long and Estella Roberts Popovich, who divided it into 14 apartments, each with a bath and kitchen. It was referred to as Echo Manor Tourist Home in the 1950s, and travelers on the National Road would stop for the night, much in the manner of a bed and breakfast. Between 1949 and 1995, Echo Manor changed hands six times.

THE BROTHEL LEGEND

Another common story about Echo Manor is that it was a brothel run by the mistress of famed Wheeling racketeer Bill Lias. She drove a white Cadillac, the stories say, and it was often parked in the driveway. Some Wheeling historians disbelieve the story while others are quite certain it’s true.

Alma Mae Henderson was Wheeling’s famous madam. She did have a white Cadillac. And research indicates that while Henderson and Lias did not have a romantic relationship, Echo Manor was indeed a brothel. From time to time, visitors to the building offer nuggets of history: a delivery man once recalled that “the women entertained downstairs and lived upstairs.”

THE WINDOW

A large stained-glass window dominates the landing on the staircase. It was created by Wheeling’s Cox family, master glass craftsmen and owners of Wheeling Stained Glass Works. The family emigrated from England to New York City in 1888 at the behest of Louis C. Tiffany (yes, that Tiffany) and eventually landed in Wheeling. Echo Manor’s window is a blend of Victorian and Classical styles with both Japanese and Greek influences. The design undulates to mimic the movement of waves. Every year in mid-July, the sun rises exactly in line with the window, and it glows in the mid-morning light. Today, you’ll find Cox windows around Wheeling, as well as at Oxford University in England.

YOU DIDN’T BUY A TUX THERE

Echo Manor comes up often in the Memories of Wheeling Facebook group. Former apartment residents remember the staircase and a payphone on the main floor. They remember playing in the hallways and visiting neighbors. Some recall that the stained-glass window depicts a bird — an eagle or a vulture.

One extremely common memory folks share is buying formal wear at Wickham’s in Echo Manor. Perhaps you rented a tux there in the 1960s for your prom or wedding. People often stop by Echo Manor and reminisce about the days when it was Wickham’s.

But memory is a tricky thing. Wickham’s was never in Echo Manor. (Nor is there a bird on the stained-glass window.) So where did this collective misconception come from?

In the famous race photograph, there’s a home beside Echo Manor. At the time of the race, it was brown, but in later years, the building was painted white. And when you see the photograph of the two homes together, both white and of similar size, it’s easy to see how people confuse one for the other in their memories, especially now that Wickham’s is gone.

This phenomenon — a group of people all remembering the same, incorrect thing — is called the Mandela Effect. (Most people remember Nelson Mandela dying in prison when he actually died in 2013.) It illustrates how we value memory as a tool for accuracy. In reality, memories are pretty unreliable, which is why the Echo-was-Wickham’s recollection continues. It isn’t until we’re presented with a photograph of the two houses together that we realize how Wheeling’s mini-Mandela Effect occurs.

126 YEARS AND COUNTING

For over 40 years, the building continued to be apartments. It seems everyone knows someone who lived there. In the 1990s, Echo Manor almost met its end, as there was a plan to raze it and build a newer office building. Fortunately, through the efforts of historic preservationists and the support of the community, the home was spared and is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Echo Manor was purchased by the Jackson Law Office in 1995 and converted to offices. The original wood, mantles, moldings, entablatures and other details remain intact. Tenants include the National Youth Advocate Program, Wheeling Board of Realtors, Bryan Wealth Management, Benchmark Investments & Insurance, and Mountain State Inspections.

So many Wheeling residents have known, lived in and loved Echo Manor. It stands as a nod to Wheeling’s remarkable past, and it has endured for over a century as one of the city’s most recognizable landmarks. Gibson Lamb couldn’t have known that his dream home would endure, that it would witness many foot races over the years, but his legacy reminds us that the threads of Wheeling’s rich history continue to weave their way through our modern lives.

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.